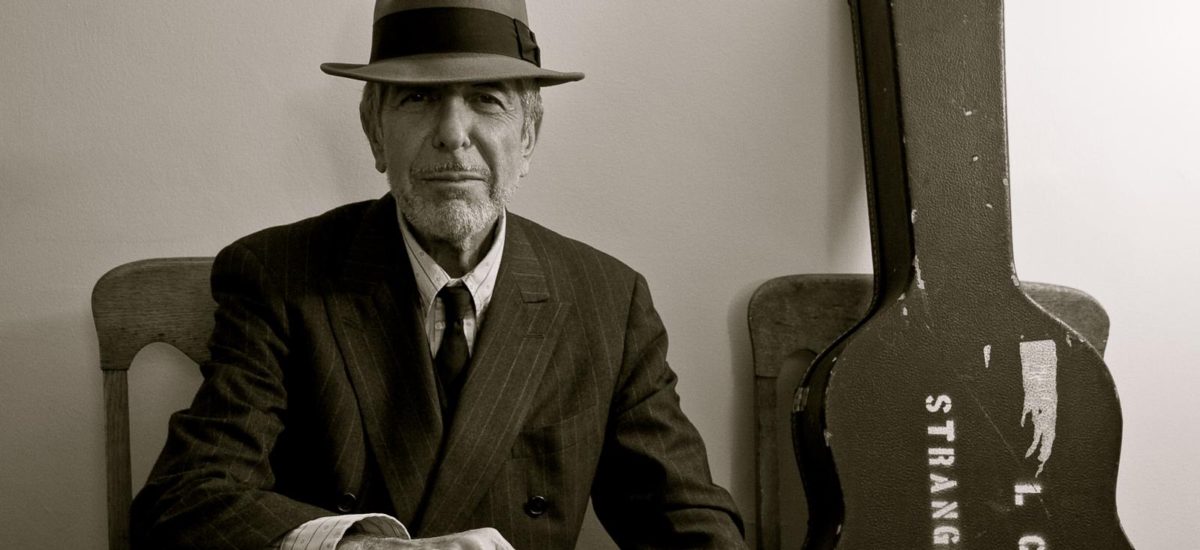

Featured image courtesy leonardcohen.com

The master of the modern love song, whose intricate and intense musical cartography of the relationships between men and women provided the soundtrack of our private lives, has come down like Moses or Zarathustra from the mountain, gaunt, courtly, priestly, yet slightly noir-ish in broad-striped double breasted charcoal suit, tie-less, fedora perched rakishly on his silvering hair as if Bogart had somehow grown old gracefully.

Five encores I think there were, but it may have been one more, for this 74 year old, finishing the performance one hour later than planned, bowing to the audience, fedora doffed and held close to his heart, eyes softly shining.

The man is what he has always been, what he was from the beginning, before he sang. Leonard Cohen is a poet. He reminds us of this, reciting, not singing, one of his later songs in entirety – “A Thousand Kisses Deep” – which I remember from a movie scene with a weather-beaten Nick Nolte looking out of the hotel window at the casino he is about to rob, the cropped haired girl sleeping on the sofa curled up after her fix, lost.

Not so much poetry set to music as poetry set in music. In the beginning and the first decades his songs meditated on the metaphysics of man and woman in love and lust, the Woman as the Other (not “the other woman” as in callow country music), angst finely wrought into art, but never overwrought.

The angel of angst has aged. The voice remains smoky, deeper than before, but instantly recognizable like those of Dylan and Van Morrison. Cohen has done with his voice that which Clint Eastwood has with his face, transmuted aging into an instrument of art.

He has always had women collaborators, and one remembers Jennifer Warnes and Anjani (his “partner in life”), but no one has played as big a musical role as Sharon Robinson, who is on stage with him at Montreux, classically trained pianist and blues-tinged jazz singer who has scored many of his latest songs.

At Montreux, Leonard Cohen has modified the music of some of his songs, turning Bird on the Wire blue-tinged. Again a new, blues opening riff and next to me Sanja is already cheering, recognizing as I have not, the opening of “Hallelujah” which Cohen delivers in genuflection, eyes shut, then rising, upright, face upwards, eyes still unopened, giving voice to his Psalm.

“Suzanne” he sings straight, the old introductory chords from his guitar, eyes open, looking into the crowd, changing a line: “And you know that she will find you…” Each one of us remembers when we first heard of Suzanne, a different kind of girl.

It wasn’t the first time I had heard Leonard Cohen. That was at the Liberty cinema in Colombo, as Warren Beatty walked through the mist across a rickety foot bridge, reins in hand, his horse behind him, the camera catching the crystalline dew drops, in Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller, a completely distinct, unique voice coming over slow and deep with the opening bars of “Stranger Song”. I committed the credit to memory – Leonard Cohen – and went in search of his music. For not quite four decades he has inhabited my inner landscape and finally I have caught up with him. At Montreux he does not sing the signature “Stranger Song” (his 2003 volume of selected poems and songs is called Stranger Music) but does “Sisters of Mercy”. In the cinema of my mind I see the silhouette of women on burros against the hilly skyline at sunset in Altman’s movie as the song was sung the first time I heard it.

The soundtrack of the Altman film is from his debut album The Songs of Leonard Cohen and at Montreux he follows up “Sisters of Mercy” with “So Long Marianne” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye,” from it. The evening’s songs are selected from all the albums but most seem to be from the last three. “First We Take Manhattan,” “Ain’t No Cure for Love,” “Everybody Knows,” “I’m your Man,” “Take This Waltz”, “Tower of Song” ( all from I’m Your Man); “The Future,” “Closing Time,” “Anthem”, and “Democracy” (from The Future); “In My Secret Life”, “A Thousand Kisses Deep” and “Boogie Street” (from the latest: Ten New Songs).

Cohen’s homeland is the human heart and he lives in its labyrinth. Nietzsche’s master-slave syndrome, applied by Sartre to the foundational dialectic relationship, man/woman, is poeticized and set to elegiac music by him, studded and strewn with Biblical metaphor and allusion. But Leonard Cohen is not only the sketch artist of naked emotions and plumber of inner space. He occasionally walks into a different dimension, reflecting ironically on late modernity and post modernity, as in “First We Take Manhattan”, “Democracy Is Coming to the USA” and “The Future”.

This is his only concert in Switzerland. He tells us when he last played in this hall he was “sixty years old, just a kid with a crazy dream”. Now, fourteen years on, at the 42nd Montreux Jazz Festival, where is he at? On our way into the Stravinsky auditorium Sanja had shown me the verse from his Anthem on a T shirt:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

He has assembled a sensitive, gifted backup band, Javier Mas on Spanish guitar (with whom Cohen often communes on one knee), Dino Solo on the sax and wind instruments, Neil Larsen on keyboards, Rafael Gayol on percussion, Roscoe Beck on bass, Bob Metzger on guitar, and Cohen’s chorus of angels – Sharon Robinson, and The Webb Sisters. He indicates a time that he could not write, and sings the first verse of the prayer that he composed at and for those moments, If It Be Your Will (from the album Various Position, as is Hallelujah).

If it be your will

that I speak no more,

and my voice be still

as it was before;

I will speak no more,

I shall abide until

I am spoken for,

if it be your will.

He leaves off after this opening verse, inviting the Webb Sisters to sing the rest and you understand, as Hattie plays the harp, why he repeatedly calls them “the sublime Webb Sisters”. A classical sketch of a woman, one breast outlined, playing a harp, is on the back cover of the souvenir as the motif of the 2008 world tour.

The mystique of the reclusive, emotionally masochistic bard in black – Field Commander Cohen, the title of a 1979 album – has lightened, thinned to the more accessible human essentials of a man in communion with others, offering his gift of song not to an elusive, fickle muse but to a deity of song or perhaps to humanity; to all of us. This is a man enlightened, made lighter and lit up from inside, by the way he has aged, his explorations into “the religions and philosophies” as he put it last night. As he has grown older, his voice huskier, his music is about letting go, standing back, bidding a long goodbye.

If you enjoyed this post, you may find “Shrillness of Nonsensical Cultural Politics and the Social History of a Song” and “changeABLE cohesion: Dance and disability” illuminating.