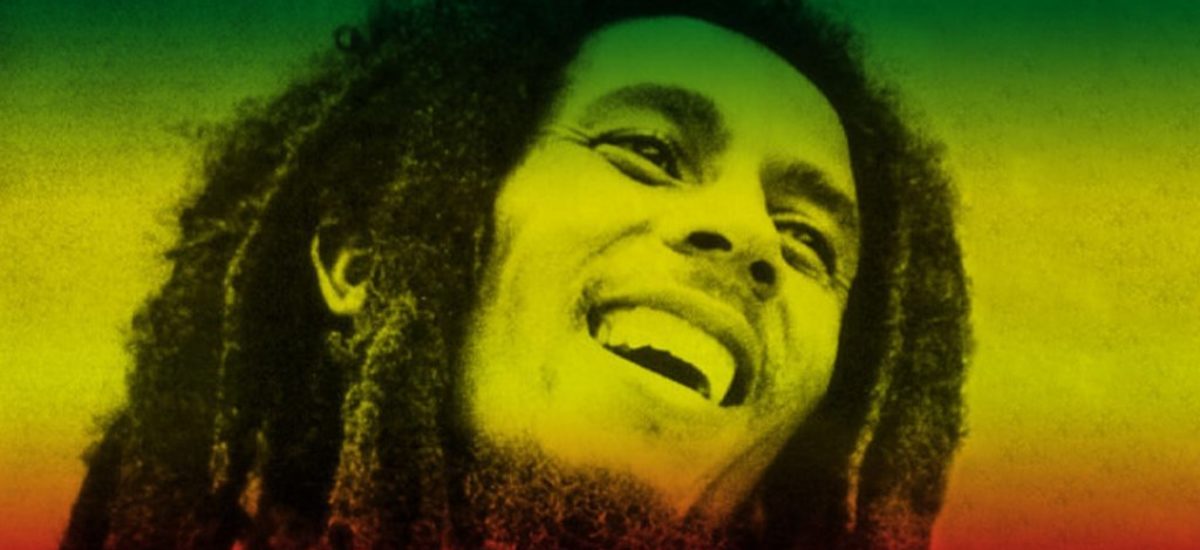

Photo courtesy of myhero.com

In Sri Lanka, the face of Bob Marley is a recurring visual motif- from tuk tuks, to street art, to reggae bars on the beach, and adorning various paraphernalia. But how did he come to occupy this visual space as a cultural icon? His face did not simply appear; it tells an integral story of resistance in Sri Lanka.

In popular representation, Sri Lanka and Jamaica are both subjected to a single story; desired tropical paradises, privy to the constant gaze of exoticism, and offering tranquility as a ‘Garden of Eden’ of sorts. Of course, this offers an unnatural construct, rooted in otherness, of these two countries. The shared histories of colonization, rampant corruption, and violent struggles quickly disrupt this single story; their narratives are complex and layered. And, just as Jamaica comes to represent an idyllic place with a turbulent underbelly, Bob Marley very much embodied this same essence. Often hailed as the King of Reggae, a symbol of the legalization movement, and a face of pacifism, Marley’s life was far from apolitical and conflict-free. Rather, Marley occupied a distinct social, political and cultural space as a musician, cultural icon and voice for Jamaica’s political struggles, as he threatened and undermined the political institutions of the country. The similarities between Jamaica and Sri Lanka’s histories, therefore, make Marley a relatable face of resistance.

Jamaica in the 70s: A Playing Field of Political Violence

The rise of socialism in Jamaica entered a decisive chapter in the mid 70s, in the lead up to the 1976 elections between Edward Seaga’s Jamaica Labor Party versus Michael Manley’s People’s Nationalist Party. The incumbent People’s Nationalist Party represented Jamaica’s socialist, leftist course, preparing the country for Manley’s fully-realized brand of socialism. The Jamaica Labor Party, on the other hand, positioned Jamaica to enter the capitalist market world order as a competitive player. In this tense electoral period, the result was a bloody feud between local garrisons loyal to either party – Kingston became a ‘checkerboard of war zones’, wherein local garrisons were bolstered to take up arms, and push the political battle on the streets. Jamaica became a hotbed of violence; polarized along political party lines, where the poor, the everyday folk, the working class, were co-opted to fight a political war.

Unwillingly and unknowingly, Bob Marley himself was co-opted into political campaigns, often being used as a symbol of Michael Manely’s party and the political left. Recognizing that he was becoming a pawn in a political war he did not support – and even surviving an assassination attempt on the eve of the 1976 elections – Marley turned to a practice of deinstitutionalized politics: operating his political position, beliefs, and activism outside of the sphere of mainstream and institutionalized party politics. Marley’s music, community initiatives, and force as an activist became his own political field, based on the tenets of Rastafarianism. He adopted a non-aligned approach to politics, famously declaring “We no defend Marxism, nor capitalism. We are strictly Rasta!”. He recognized the two political ideologies of left and right, Marxism versus Capitalism, as polarizing and divisive forces in Jamaica that had little to do with party ideology, and everything to do with oligarchy and personal power aspirations. Nonetheless, Marley’s fierce convictions never relegated him to a sphere of apoliticism or apathy – he was always a firm activist, spokesperson, and figure of radical discourse.

It is concurrent to these events that the message of Rasta gains widespread traction in Jamaica, largely popularized by Marley’s commitment to the movement and rise as a cultural icon. Rastafarianism is a social and religious movement, originating amongst Afro-Jamaican communities in the 1930s, and articulates a consciousness surrounding Black liberation. Rastafarianism iterates ideas of pan-Africanism, and the return to the continent for rooting the Black liberation struggle. When Marley began embracing Rastafarianism in the 60s, Rasta was a religion of the poor. The biblical parallel was the fight against Babylon: the system of oligarchy, whereby few powerful elites monopolize and centralize their hold on power over the many. And, his essence was the unity of peoples – White and Black – to which he famously stated, “Well, me no dip on nobody’s side. Me no dip on the Black man’s side, nor the White man’s side. Me dip on God’s side”.

A Face of Resistance: The Appeal of Bob Marley in Sri Lanka

The parallels are apparent. With our own history of socialist insurrections, a struggle against chronic corruption and elitism is revealed. The first socialist insurrection led by the JVP in 1971 was Rohana Wijeweera’s ideological battle; emphasizing a Sri Lanka-specific approach to Marxist revolution. Analysts also argue that the first insurrection was a rebellion against the Queen, and Britain itself, for its centuries of colonial rule. The 1989 insurrection took place at a heated conjuncture in history, now a fully-armed revolt using indiscriminate warfare against military and civilians alike. But these socialist insurrections were devastating failures, claiming over 70,000 lives in the Southern conflict alone, and quickly convoluting the original fight for the proletariat. An ethnic angle overshadowed the cause, merging the JVP with a Sinhalese-Buddhist populist movement and effectively exacerbating ethnic divisions between Sinhalese and Tamils. Marley’s own criticisms of the political left, which he recognized as an equally destructive force when distorted by ideological primacy and draconian enforcement, thus attracts popularity in Sri Lanka – whereby an entire generation, and generations to come, have become disenfranchised by the dogmatic socialist front due to the collective memory of its disaster and carnage.

Hence, Marley becomes an attractive figure to Sri Lanka, as he embodied much of the popular sentiments against oligarchy – but with a far more nuanced and humanistic approach to violent struggles and revolution. Marley was peaceful, and denounced the message of senseless violent revolution. But, Marley was far from a pacifist; he defended the armed struggle for Black liberation, and recognized that armed solidarity was crucial to the fight for rights. In this way, Marley better situated himself with thinkers such as Franz Fanon, rather than those of a purely Marxist orientation. Marley consciously engages in class struggles with the intersectional dimension of colonization and the construct of the third world, recognizing that colonialism was a state of total violence that could only be overturned through violent decolonization processes. This is, of course, a derivative of Fanon’s philosophy. However, as Fanon’s New Humanism explains, counter-violence is inevitable at the beginning of the revolution – but it is not to be sustained. The ultimate goal is therefore to build a new world order based on mutual recognition and love of humanity, both between former colonizers and the colonized. Here, Marley’s preaching of love and unity, of Rastafarianism and peace, are revealed as an amalgamation of post-colonial revolutionary thought that promotes the unity of humankind.

Of course, Marley’s overall rhetoric is progressive and left-leaning. But, his direct and personal interactions with the political left and right was proof that neither end of the political spectrum guaranteed true liberation for the poor and marginalized. Thus, his advocacy for an alternative form of socialism – one particularly concerned with a united front against colonization, oligarchy and wealth inequality – resonates within the Sri Lankan context. Marley’s humanistic revolutionary thinking, which distinguishes between the need for violent decolonization as a vehicle for liberation, versus operating as a state of violence, is particularly attractive to Sri Lanka – a nation that has dealt with years of civil war, bloody insurrections, government-sponsored violence, and local conflicts.

“Every man gotta right to decide his own destiny,

And in this judgement there is no partiality.

So arm in arms, with arms, we’ll fight this little struggle,

‘Cause that’s the only way we can overcome our little trouble”

– Bob Marley, Zimbabwe, 1979.

Just as inner-city neighborhoods in Kingston became a playing field for party violence, pushing political battles onto the street is endemic to Sri Lanka – rarely do political battles shake the elitist core as they do for the everyday civilian. Marley critiqued this phenomenon with acute understanding, once again a probable factor behind his popularity in Sri Lanka today. Among Sri Lankan governing elites, there is an elitist solidarity that operates bizarrely, and almost exclusively, away from the public sphere. It appears to transcend partisan lines, political alignments, and even ethnic and racial lines that dictate so much of Sri Lanka’s internal conflicts today. It is why we see powerful political families on a first-name basis, attending each other’s weddings, socializing and participating in class solidarity. All the while, their political battles are carried out on the ground, with mutually-vilifying campaigns that attempt to delegitimize the other. It is also why wealthy businessmen from minority communities – notably, Tamil and Muslim – are coopted into elite political circles and recognized as a crucial business lobby, continually fluctuating between the SLFP and UNP. Meanwhile, ethnocentric, racist and intolerant sentiments are played out on the ground. It appears then, that political dissent only touches the poor; the deinstitutionalized; the vulnerable everyday citizens. How much are political institutions actively working to redress popular grievances, rather than exacerbating cleavages for a political agenda?

Bob Marley’s ‘Deinstitutionalized’ Politics

Bob Marley is often idolized as an apolitical figure, taking a formally politically neutral stance in an attempt to disengage Rasta from politics. To politicize the message of Rasta would run contrary to the crux of the movement – it would fall in line with the very institutions it attempted to dismantle and discredit, and it would inevitably result in division among members. Marley was, however, far from apolitical. While he did not buy into partisan politics, he illuminated a political consciousness through his message of Black, and poor, liberation. And, his political messaging transcended partisan party lines, and elitist political constructs. Marley’s acclaimed song, “Zimbabwe”, was a revolutionary ode to the independence-fighting rebel forces of Zimbabwe. The wealth of his politicized music comprised a repertoire such as “Exodus”, “Survival”, “Blackman Redemption”, and “Redemption Song”. “Buffalo Soldier” is the iconic liberation anthem of the Black resistance. “Get Up, Stand Up” is the politically charged call for the defense of one’s rights. He adopted an uncompromising dedication to Black African liberation, delivering three crucial albums – Rastaman Vibration, Exodus and Kaya – with an uninhibited voice for the pan-Africanist cause. Throughout his career, Marley engaged in a political consciousness that fell beyond the scope of political institutions. And of course, deinstitutionalized politics is in itself revolutionary.

It is unsurprising then, that many Sri Lankans identify with Marley’s deinstitutionalized politics. Feeling unrepresented by the political institutions that govern us is not apolitical – rather, it speaks to a dissatisfaction with the current institutional arrangement. Organized movements that have attempted to dismantle the status quo, such as the JVP insurrections, resulted in tragic losses that ultimately derailed their initial struggles for an equitable and transparent society. And, in formal politics, there has never been a Sri Lankan government that has not privileged the status quo. Regardless of the party holding political power, Sinhalese Buddhist supremacy is always the crux of the Sri Lankan political establishment; for example, Gnanasara and the BBS were endorsed under the SLFP, yet Gnanasara was granted presidential pardon and release from jail under the UNP. There has never been a government that has guaranteed full and free liberty of the press – from “white van” disappearances, to the assassinations of some of the country’s most esteemed and outspoken journalists: Richard de Zoysa, Taraki Sivaram, Lasantha Wickrematunga, and numerous others, which span over the course of both SLFP and UNP governments. There has never been a government that has effectively responded to corruption; even with the promise of Yahapalanaya, nepotism and corruption scandals continued. By the very virtue of our political arrangement, women and minorities have never been accurately represented by our government. Women, for example, constitute 52% of the population, and 56% of the voter population. Yet, women remain chronically disengaged from the political sphere, and comprise only 5% of the parliamentary legislature.

Inherently, however, recognizing a lack of representation within preexisting political institutions is also taking a political stance. We are far from an apolitical nation – rather, many Sri Lankans simply feel disengaged from political institutions, and practice their political life via alternative outlets. Polarized party lines have not equated to contrasting political platforms; the facade of left versus right, and progressive versus conservative, proves to veil a common desire for elitist power centralization. To then measure the power of one’s political engagement through institutional support and partisan lines is fundamentally misleading – especially when those institutions are never intended to reach the poor, the marginalized, and minorities. Disengagement, deinstitutionalization, and grassroots activism, could instead prove equally compelling courses.

Resistance in Sri Lanka, as in Jamaica during Bob Marley’s time, follows a shared narrative of opposition to elitism and oligarchy. The beaming face of Bob Marley that shines on your average tuk-tuk is a reminder of our own tumultuous struggles for freedom. And, there is something so refreshing and hopeful in this face of resistance that we see across Sri Lanka today. It tells us that our revolutionary struggles are far from over – that we have much to learn and unlearn from, and much to work towards.