Reaction to the recent programme by UK’s Channel 4, Sri Lanka’s Killing Fields, has great variety, ranging from “Ah, didn’t we tell you all along, the Sinhalese and their army are nasty people,” from the side of a vast majority of ethnic Tamils, to, “Oh no, such horrors never happened, this is all just manufactured propaganda from the residuals of that terrorist outfit and its sympathisers,” from the Sri Lankan government and its supporters. The build up to the broadcast, in which the producer brilliantly increased the size of her viewer population by appealing to a kind of negative psychology: “please don’t watch my programme,” however, was too much to take for a particular Sri Lankan Tamil man, because, from simple back-of-the-envelope calculations, he already knew exactly what was in it.

This Sri Lankan Tamil Man, whose story I am about to tell you, is a peculiar character whom we have met in the pages of Groundviews before, and is none other than Sivapuranam Thevaram. We have read about the structure of his name, about the debt he owed his father and the extensive travels he undertakes as a consequence, and the reasons for the infinite sorrow of his mother, Sivahamy. We have also read about how his bicycle got stolen at the Bridgetown railway station, back in September 2010.

Thevaram decided he could not watch the horrific scenes in the Channel 4 programme. He couldn’t stay in the UK and not watch it either. So he decided to take the cowardly path of running away, something in which he has had a bit of practice, dating back to the year 1983. He made up a flimsy excuse of his mother being ill, adjusted his work schedule, packed his bag and took a flight a quarter of the way round the world to, er…, Sri Lanka, where he spent the last week at BusyTown University, giving a seminar, discussed setting up of a research group, learnt about the difficulties of automatically translating between Sinhala, Tamil and English, and had dinner with a friend who was active in the dispute over academics salaries. His only regret during the week was that he was too busy to attend a meeting at the Open University of Sri Lanka, at which Savitri Goonasekara spoke about the future of higher education in the country. That, on the Richter scale of regrets, would certainly have been much milder than watching the way the horror of the last days of war was played out in the Vanni. Horrors of infinite magnitude which I wouldn’t say are unimaginable, for I have seen it all in 1971, on the highway between Bandarawela and Wellawaya. We, the Sri Lankans, never learnt a lesson from that, and proceeded to repeat the whole show in 1989 when our youth rebelled again. So what chance is there that we would learn a lesson now, other than setting up a commission specifically designed not to learn lessons? What difference does the existence of an ethnic or linguistic divide make now? Is not the lowest common denominator between 1971, 1989 and 2009 so big, that the ethno-linguistic differences in the present issue are insignificant? What then is the surprise in the way the vast majority of the majority are reacting in response to that C4 explosive: “Oh this is all just propaganda, we just ought to ignore all of it and move on.”

Thevaram’s reaction fits nicely with the four stage approach by which our Sri Lankan society, and the governance we sustain, has evolved to come to terms with the way it deals with its youth: ignore-bang-kill-forget. No wonder the hypocrite Thevaram calls himself a “Sri Lankan Tamil, in that order.”

When I met him, he was sitting in the departure lounge of the Colombo airport, having already consumed a couple of pints of Lion Lager. What a convenient way to bury his head in the sand and continue to talk through the posterior end? And he did just that.

Now, Thevaram makes a living studying the properties of what is known in jargon as Markov processes, which says that the future state you might find yourself in depends only on the current state, and not on the history of how we got to the current state. A game of chess is a good example to illustrate this. How it will end, from some position half way through the game, depends only on what position the pieces are currently in, and not necessarily on how exactly they got there. Of course, it is an approximation, as it ignores factors like your being able to make judgements about the opponent’s plans based on the sequence in which (s)he might have dragged you into there.

That Thevaram resorts to Markov processes to discuss politics with me suggests that he has an acute dislike for history. Time zero of Sri Lankan history, according to him, is February 1948, when the British left the island. He refuses to acknowledge the usefulness of anything that happened before that, be it the amazing Sinhala Buddhist civilization in the island spanning thousands of years, as evidenced by the stunning irrigation systems they had devised, or the ancient Tamil civilizations in the island and the region, be it due to the South Indian emperors or those who did small scale heroics like the king Changilian in Nallur. What matters to Thevaram is that the British ruled the island, ran its administration separate from that of our big brother, India, for about a hundred years. And then they left. During their tenure, they built railway tracks and showed us how the steam engine worked. These guys, the Suddhas (white fellows), left in 1948, leaving us islanders to look after ourselves. “Did we extend the railway network by a single yard?” Thevaram asks me, “Is that not a more useful thing we should have focused on, than the glory of what we used to be thousands of years before the Suddhas arrived?”

“Despite our ethnic differences, talked about so much, this lowest common denominator,” says Thevaram, agreeing with my reference to 1971, 1989 and 2009, “is that the genetic make-up of the islanders is all the same.”

“What proof do you have of that?” I challenged him, knowing all too well that the man had expertise in modern molecular biology, and might lecture me on the complexities of genome sequencing and comparisons. But Thevaram had a different answer, not at the rudimentary level of the genome, but going well beyond.

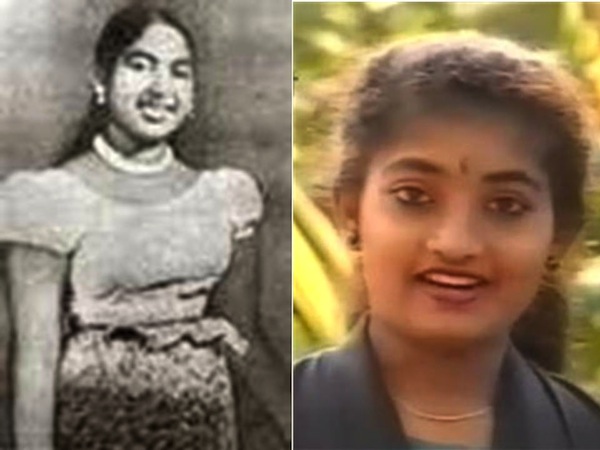

“I have the perfect proof in two Sri Lankan women,” he said, “one called Premawathi Manamperi and the other known as Isaipriya – work it out yourself!”

Figure: Two Sri Lankan women with striking similarities in their genetics: Premawathi Manamperi and Isaipiriya (Images taken from http://www.lankaenews.com/Sinhala and http://www.tamildaily.net). When will we ever learn a lesson?

“You know,” Thevaram said sipping his lager, “as far as the way I will behave in the coming years, my decision is made, and that is this.” He gulps the last drops and says with determination:

“My future is not in the past.”

What a hypocrite, would you agree?