My name is Polgahawela Aarachchige Junius Soloman Hickmana Thanthiriya Bandarawela, and I am a taxi driver in Colombo — you can call me Hick, for short. I am about to tell you my encounters with a Sri Lankan Tamil fellow, Sivapuranam Thevaram. This man hired my taxi three times in the last couple of years, twice for airport drops and once on a weekend trip to Dambulla. Thevaram is someone best described as a “Kalu Sudda” [Black, White man] – black skin, but carries a Thatcherland passport. Often he thinks and behaves like these foreign fellows, with his priorities in stuff like individual liberty, journalistic freedom and human rights, worrying about these just the same way I do about the cost of rice, petrol and milk powder for my children.

There are many of my countrymen like Thevaram. They get themselves free education here, do not work here or pay taxes and emigrate to richer countries. A peculiar recurrent thinking in their ways, often triggered by the wine they consume, is the thought of returning home “in a couple of years”. “When I finish my Pee Etch Dee”, “After a couple of years of work experience”, “When the kid finishes college”, etc. but this “in a couple of years” is a bit like pigs flying. It never happens.

Thevaram is a hypocrite. For example, he is strongly opposed to private education and has sworn that his kids will study in state schools. But he chooses to live in expensive neighbourhoods where the state schools are known to be good – as good as Royal or Jaffna Hinthu College. He pays via the premium on house prices in catchment areas of good schools. Similarly, cowardice is also his strong attribute, as he is usually scared to speak out on issues of social and political relevance. If any of you readers score lower on these two metrics, you should teach this fellow a lesson (but “Judge not lest ye be judged”, I warn you.)

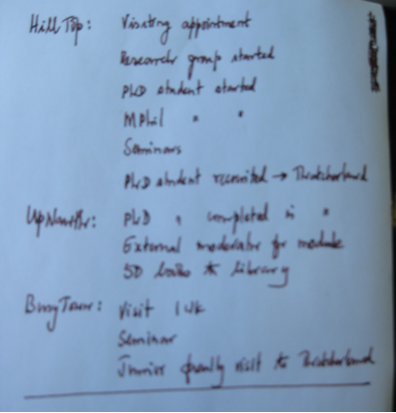

After my latest hire for Thevaram to Katunayake airport, I noticed he had left behind in my car seat a piece of A4 paper, of which I took a picture.

Apparently, the man has been doing some collaborative work at universities in my country (HillTop, UpNawth and BusyTown). I was pleased with his patriotism in coming back to work in Sri Lanka, but this modest list set me thinking: What would this work be worth? Suppose he kept up this momentum for another ten years, would he have paid back enough to offset the debt he actually owes us? Who has the moral authority to sit in judgement over his self-made contract of a repayment plan? With whom exactly is his contract anyway?

To answer the last question, we go back two years. I had to drive Thevaram family (the man, his wife Manimekalai, his three kids Sathuram, Samanthiram and Senguthu) for a weekend holiday to Dambulla. When I went to pick them up in Batharamulla, I found Thevram pacing up and down the lane, impatient to get started. “Lets go, come on, what is the delay?” he kept shouting. “Ungalukku enna visarE, ippa enna avasaram?” [Are you mad, what is the hurry] Manimekalai shouted back. That raised his temper, I could tell from the increased speed of repetitive pacing. When we eventually set off, the atmosphere in the car was tensed: Thevaram biting at his lips, Manimekalai scolding the children, and Samanthiram and Senguthu quarrelling over some chocolate.

As we passed the parliament, there were some monkeys on the road. An opportune moment to cut the tension in the car, I thought, and said “Parliament ekE tea-break, Sir.” Thevaram let out a loud burst of laughter, the kids got the joke immediately, Manimekalai missed it (“What, what?”) and I achieved my goal.

After climbing Sigiriya we visit the Dambulla rock temple, amongst the finest places of historic interest in Sri Lanka. The family, in our typical Sri Lankan style dare I note, mingled with a group of tourists who had a guide. The guide was explaining the history of the place, all about how the Sinhala Buddhists had to protect sacred items from invading Tamils. In the guide’s explanation the Tamils were demons and the Sinhalese were victims of invasions. There is truth in it, I agree, yet it was a bit of a half-story. I had wondered from the rock in Sigiriya, earlier that day, the context of Inthian invasion of those times. It was a Lankan prince who fell out with the father, treated him rather harshly, and it was the brother of the prince who went to Inthia and invited a Hanuman army to sort the sibling out. Wasn’t it?

Manimekalai was upset with the guide, but Thevaram was entirely oblivious. “Around the same time as the Romans were building roads and sewage systems,” he explained to Sathuram, “our people had an advanced civilization in these parts. You should not think that civilization originated in Europe and our ancestors were living in trees and caves.” Now I get it! This is not a holiday. This is a pilgrimage, to show off his roots to the kids. Yet I am puzzled. A Tamil fellow in a Sinhala Buddhist shrine is saying “our ancestors”? Does he not know the difference?

Last year, I drove him to Kanatte for the funeral of his father. Sivapuranam comes from a small village in the North with very basic facilities (no running water, no water-sealed toilets etc.), but post-independence social mobility in Sri Lanka was bloody good, with hard work and a bit of luck. Even Amartya Sen has written about these things. High literacy rates, reductions in infant mortality rates, and in eradicating some diseases like malaria, we made good progress. Sivapuranam could get himself educated at Jaffna Hinthu and then graduate from HillTop. He lived through difficult times of three wars, but showed no interest in emigrating like his children or other asylum seekers. Sri Lanka was home to him, he stayed on, practicing his trade, well past formal retirement.

As a little boy, Thevaram once scored high grades at school exams. Jumping up and down in joy, he had sung: “I am the most intelligentest kid in the whole school.” Old man Sivapuranam then told him a story, about a fellow he had hired to cut down a tall coconut tree. The cutter was a chap with no formal education. Sivapuranam was nervous about the tree falling on the house. Noting his anxiety, the chap drew two straight lines on the ground, at about 20 degrees to each other, radiating away from the foot of the tree. “Watch Sir,” he declared, “I can get it down between these two lines, if it falls outside these you don’t have to pay me.” The man with formal education accepted the bet and lost. The young boy learnt humility from the story.

At Sivapuranam’s funeral, Thevaram has just one image in his mind of the father. Some months after that Dambulla trip, Sivapuranam fell ill. Thevaram had come to see the old man and has made that recurrent comment: “may be I will wind up in Thatcherland and come back and work in Sri Lanka.” Sivapuranam’s face lit up at that remark. Though the old man had full knowledge of the impossibility of pigs flying, the thought of the son returning to Sri Lanka had given him momentary enormous pleasure. That pleasant calm smile on the father’s face made a permanent impression on the son, and he allocated several million synaptic connections to save that image in his long term memory.

Driving back from the funeral, he leaves his iPhone in the car and goes to buy a thambily [young coconut]. I gently peeped into the screen and saw a draft email, of which I took a photo:

The mystery of that self-imposed debt repayment plan is now clear, no?

[Author’s Note: The characters and events are fictitious. Any similarity one might note to real persons is pure coincidence.]