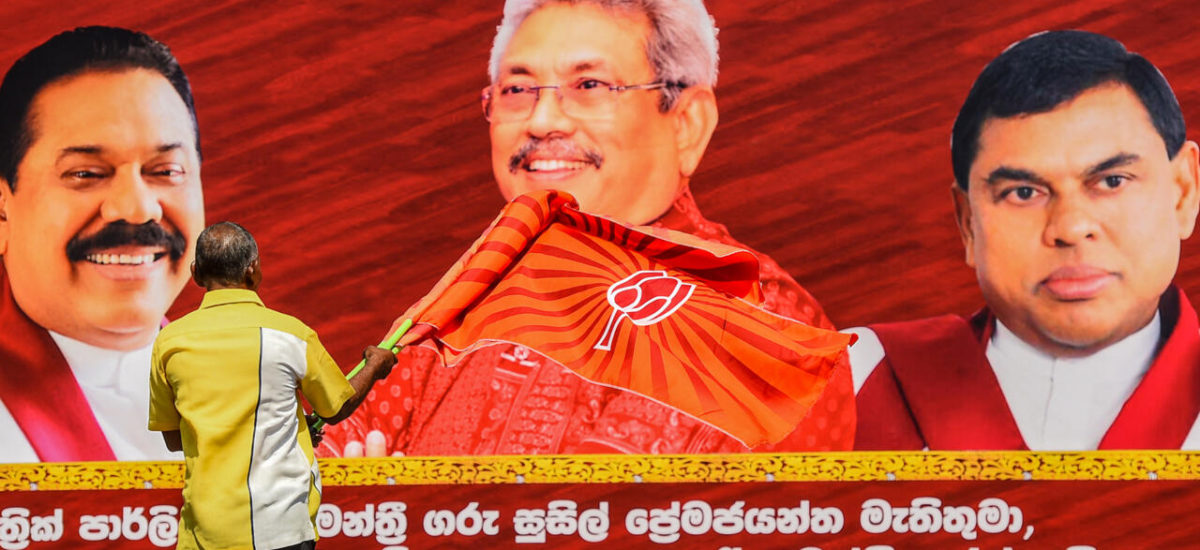

Image Credit Ishara Kodikara/AFP

Ever since the years of de-colonization, South Asian politics has been tainted by dynastic politics or, simply, nepotism. Has it become embedded in the culture of the region or is it simply a product of the unending cycle of corruption that is inherently rooted in most South Asian systems of government?

Before exploring individual case studies on dynastic politics, I would like to mention a few names synonymous with politics: the Gandhis in India, the Bhuttos in Pakistan, the Bandaranaikes, Senanayakes, and Rajapaksas in Sri Lanka. These families despite carefully crafting their legacy, have left behind the metallic taste of cronyism, advantage and ill-governance.

So why has dynastic politics been so heavily criticized? The most cardinal issue is that the merits of meritocracy are removed and preference is given to a family member irrespective of their competence for the position. It also reduces the democratic health of the country while it encourages one family to consecutively hold onto military, political and economic power. The only pre-requisite for political advancement then becomes family kinship. This article will discuss narrowly two examples of dynastic politics from 20th century Sri Lanka.

In immediate post-colonial Ceylon, the Senanayake family dominated Ceylonese politics with the Honorable Don Stephen becoming the first prime minister of independent Ceylon. Closely following his father, Dudley Senanayake became heavily involved in state council affairs (in British Ceylon) and was elected into the first cabinet of independent Ceylon, (headed by his father!). In 1952, D. S. unexpectedly passed away and Dudley was chosen as the second prime minister of Ceylon. He called for a general election in which his party the United National Party won. Dudley held recurring terms as prime minister until 1970. Whilst this period oversaw significant advancements in agriculture, it is a pertinent example of dynastic politics.

The 1950s watched the rise of another wealthy, elite family; the Bandaranaikes. Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike was the founder of the left-wing, Sinhalese nationalist Sri Lanka Freedom Party and the fourth prime minister of independent Ceylon in 1956. He was a proponent of nationalism, indigenous culture, and his policies were overwhelmingly influenced by his Sinhala first agenda, (leaving behind a trail of controversies amongst the minority communities). The untimely death of S.W.R.D. caused by an assassin’s bullet, pushed his widow into the political spotlight and made her a candidate for premiership from her husband’s party the SLFP. Even more so than the Senanayakes, the Bandaranaike family became the epitome of dynastic politics with Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike serving three terms in the office of prime minister from 1960-1965, 1970-1977 and from 1994 to 2000. While becoming the world’s first female prime minister, it became largely obstinate that her name carried the weight of political familiarity and confidence with the people of Sri Lanka and therefore, rather than being elected for her merits, her familial dynasty secured not only hers, but positions for her children in politics. In 1994, Chandrika Bandaranaike, the daughter of S.W.R.D. and Sirimavo Bandaranaike, succeeded her mother as leader of the SLFP and won 62.2% of the vote in the presidential election. In her first term as the first female president of Sri Lanka, she appointed her mother to the post of premier.

These are just two examples of the shadow of dynastic politics that shrouds South Asian (specifically Sri Lankan politics with the overwhelming number of politicians from the Rajapaksa family). The psychology of South Asians is such that constituents have a disposition to vote as per their allegiance to the family rather than the individual candidate, and this voter behavior is a product of legacy building by politicians. Additionally, South Asian politics is heavily influenced by the lack of economic development, and this economic underdevelopment, out of which sprouts unemployment and low standards of living, encourages voters to deflect voting for new candidates – the result being, that they repeatedly vote for familiar candidates often with political lineage, whom they have grown to trust irrespective of the competence of the candidates.