Featured image via DNA India/Ishara Kodikara/AFP

In 2017, Groundviews filed a series of RTI requests to ascertain more about Sri Lanka’s early warning system. (Click here and here to see the original RTI requests filed with the Metereological Department and the DMC respectively.)

At the time, most of the State bodies tasked to deal with disaster response appeared relatively unprepared to process RTI requests. Filing the application at the Metereological Department proved an uphill task, involving navigating through the labyrynthine corridors of the Department before finally ending up at the office of the then Director General.

The DMC was somewhat better prepared.

However, both the DMC and the Department of Metereology baulked at providing more detail about providing detail on the Doppler radar system, which has reportedly been in a state of disrepair for some time, since as far back as 2015.

The now retired Director General of the National Metereology Department, Athula Karunanayake did acknowledge that the non-functional radar had been an issue.

“If it did work, it would have improved our predictions, made them much clearer. But still you can’t predict with accuracy that it’s going to rain 300 millimeters in this specific area. It’s especially difficult to subdivide by area,” Karunanayake said.

Karunanayake provided a series of situation reports from the DMC that showed that the Metereology Department had indeed warned of heavy rain the day before flooding began. He added that the Department had made several efforts to warn people ahead of time about the weather, including writing articles to the Ravaya newspaper.

The DMC provided copies of the same reports, adding that their early warning system had largely consisted of SMS alerts (though they were unable to provide documentary evidence of the time and content of the warning messages sent out.)

As was widely reported, however, the Department of Metereology failed to predict just how heavy the deluge would be. In 2017, 600,000 people were displaced, while the year before, over 500,000 had to leave their homes. Over 200 people lost their lives in 2017. At the same time, drought affected over a million people across the island.

The RTI requests were filed at a time when there was public outrage around what was seen as State inaction, despite flooding in 2016 wreaking similar havoc. It appeared that little had been done to prepare.

Map courtesy desinventar.net, a UN open source initiative to compile disaster databases. This map shows the number of deaths due to a number of events, including drowning and accidents, and land slips

Last month, the German Climate Risk Index 2019 was released, highlighting that based on 2017 data alone, Sri Lanka was the second worst affected by extreme weather conditions.

Groundviews took some time for further study, filing a fresh request in 2018. The aim, this time around, was to learn more about the nitty-gritties of how Sri Lanka prepares for natural disasters.

While Sri Lanka has made strides in terms of response, there is more that can be done in terms of preparation. it appears that bureaucracy, a lack of political will, or both, is holding the country back from more comprehensive planning around natural disasters.

The apex body for disaster risk management is the National Council of Disaster Management, headed by the President. It is supposed to convene regularly – “not less than once in three months” according to the Disaster Management Act. Yet, as Groundviews learned, the Council has met just once in 2018, twice in 2017, and not at all in 2016.

Click here to see the internal memo on the dates when the Council met, provided via email in response to our RTI request.

Why is the lapse in meetings by the Council important? Simply because the mandate of the National Council is to map out national policy on disaster management, including deciding on the best use of resources for preparedness, prevention, response and relief.

The 9th Council, for instance, asked the DMC to develop a guideline to safeguard people in inland waters, after around 12 people lost their lives in a wreck in Tissamaharama. At that time, the DMC had read through legislation in a number of areas – over 20 different laws in total, from the Navy Act to the Fisheries Act – and developed a set of recommendations. The Council plays a vital role in directing the focus on disaster preparedness.

The reason the Council isn’t meeting may simply be because, as the DMC implied, the President was unaware that he was the head of the Council until very recently. At the time Groundviews filed the request in November, the DMC was working on an updated national policy to present to the President.

Miscommunication and bureaucracy continue to act as obstacles.

For instance, in order to begin national emergency operations, relevant approval needs to be obtained from the Ministry of Disaster Management’s Secretary. This process is not mandated by the Disaster Management Act, simply because at the time legislation was passed, there was no Ministry for Disaster Management. This approval process has, however, become accepted procedure. While this sounds reasonable on paper, it can sometimes lead to what are, quite literally, life-or-death situations.

“In 2016, the flooding started in Galle,” Assistant Director from the DMC, Chathura Liyanaarachchi recalled. “At that time, a District Assistant Director suddenly called Head Office to inform us that it was flooding.”

Assistant Director and Media Spokesman Pradeep Kodippilli had answered the call.

“He asked the informant, “Can I trust you?” The Assistant Director replied “You have to trust me.”

The message was sent out via the armed forces that flooding was imminent. Evacuation began. The DMC did not have the time to follow established procedure. “We acted in good faith, to save lives,” Liyanaarachchi said.

Rather than scrambling to respond in this way, the answer may lie in better preparation.

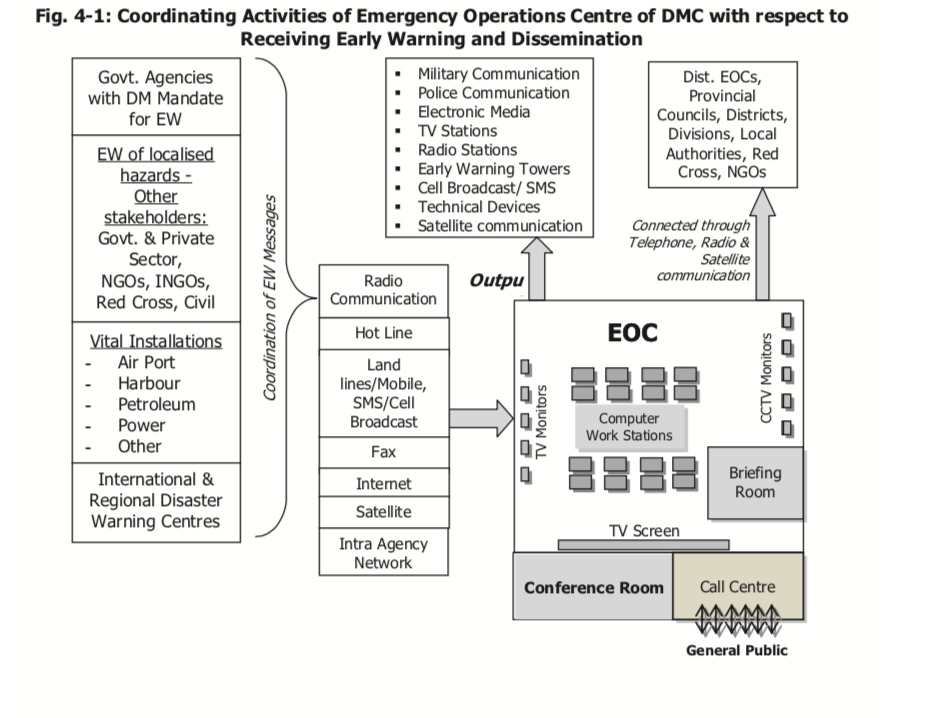

Sri Lanka does have a disaster management policy (accessible here) and a national plan (accessible here). Both provide a wealth of information including on plans to improve the Emergency Operations Centre and streamline warnings to the general public.

The value of planning in this way is obvious. Sri Lanka’s natural disasters impact swathes of the country’s population, often those who are least equipped to withstand them.

Left: Map showing the number of destroyed housing across the island, due to disaster events

Right: Chart showing disaster events that led to damaged or destroyed housing

Hazard maps, which identify vulnerable areas and routes for evacuation, are often described as a “crucial first step” for disaster management.

Sri Lanka’s hazard profiles can be found in a 2012 report, a joint effort between the Ministry of Disaster Management and the UNDP. It is worth noting that the mapping for flood risk in this report has only been completed around the key river basins, and in Colombo and Gampaha district. It has been recommended that hazard maps be completed for a number of natural disasters, particularly flooding and landslides). There are numerous barriers to overcome – for instance, the lack of availability of base maps at the required scale, and the high cost of high resolution satellite images and base maps. (see page 15 of the national disaster management plan). Perhaps due to this, updated island wide hazard maps have not yet been completed, or at least, are not publicly available.

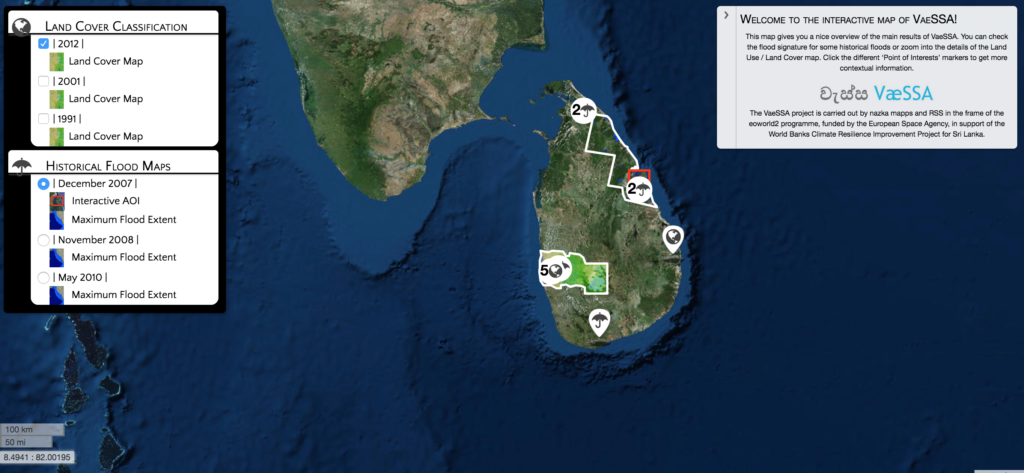

There have been several initiatives to map hazards using historical data. There is Vaessa, an interactive map that shows historical flooding (up until 2010) and land use (up until 2012). World Bank’s Climate Change Knowledge Portal also maps a number of hazards for Sri Lanka.

Screenshot from the Vaessa website

At the time Groundviews visited, the Ministry was carrying out a series of islandwide tsunami drills, so that the public would know the best evacuation routes. The DMC also highlighted several schoolbooks designed for children, on a number of different hazards, from lightning strikes to landslides. It also works with interested Government agencies, including schools, to develop their own disaster management plans.

These measures, introduced after heightened scrutiny following the flooding in 2016 and 2017, do appear to have had some results. In 2018, 26 people lost their lives, and 19,519 families were evacuated – a drop from the previous two years.

Yet while these initiatives are laudable, there is certainly scope for Sri Lanka to do more.

As Liyanaarachchi pointed out, “One dollar spent on preparation can save so many dollars that would have been spent on response.”

Many dollars saved, and possibly, many lives.

Note: Groundviews is linking the reports received as part of the RTI request below, for ease of reference.

National Disaster Management Policy

National Disaster Management Plan 2013 – 2017

Sri Lanka Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme 2014 -2018