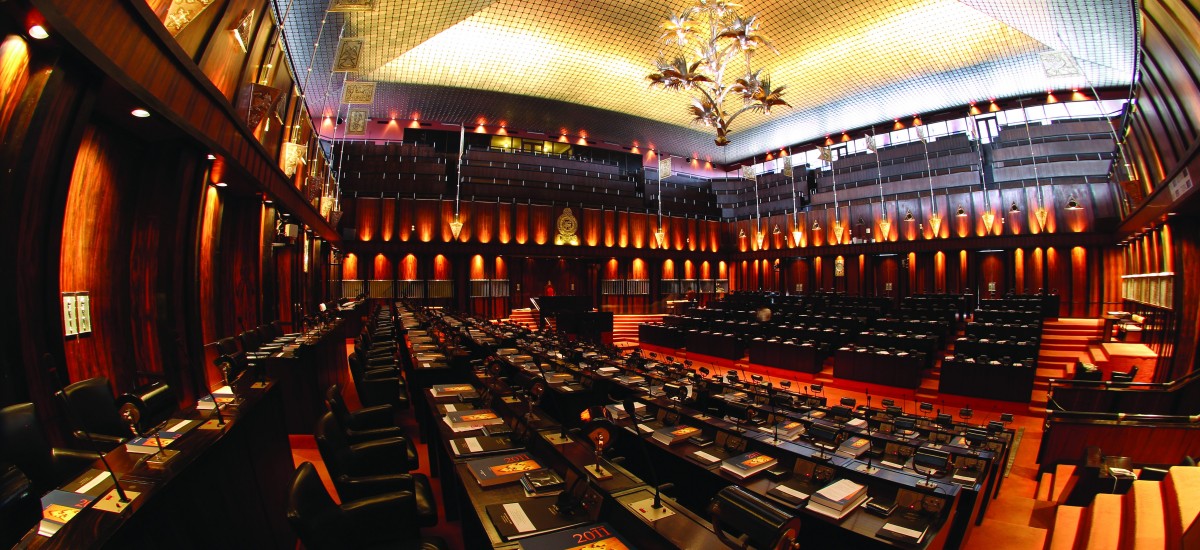

Photograph courtesy Article 14 blog

“Vous l’avez voulu [You asked for it], George Dandin” mischievously exclaimed the Soulbury Commission’s report 70 years ago implying that their recommendation of the British parliamentary system was at Ceylonese instigation if anything went wrong. The report quoted French playwright Molière’s 1668 comedy Dandin, and defended their counsel that Ceylon adopt a Westminster inspired constitution model on the grounds that not only was it best suited for the island, but also on the grounds that “the majority – the politically conscious majority of the people of Ceylon – favour a constitution on British lines. Such a Constitution is their own desire and is not being imposed upon them”. Ceylon strolled towards independence on 4 February 1948 with an unabashed fervour for Westminster government. The Soulbury Commission dutifully served an institutional tiffin that satisfied in large measure the specific appetite of Ceylon’s elite. A republic would have been as welcome as an Indian invasion, and instead, a unitary bicameral Realm within the Commonwealth was established that self-consciously saw any other style of government as beneath the dignity of the Ceylonese elect. As such the new constitution was generally deaf to the apprehension from corners in the Colonial Office, old Ceylon Civil Service hands, and the usual local troublemakers. The result was that precious few alterations were made of the Westminster model for the context, complexities, and conventions of Ceylon.

This system was more commonly associated with the British settler countries like Australia, Canada, and New Zealand where ‘kith and kin’ links with Britain seemed to make this appropriate. However, the British and the Asian indigenous elites saw advantages in applying this very British system to the very different context of the East. These Asian nations did not have centuries to interpret and adjust in order to develop their constitution as the British had. Instead within months they needed to formulate and design a constitution and therefore invariably drew upon the system of their imperial master. The local elites with the involvement of external actors like Sir Ivor Jennings determined that Westminster could work in the East. Since the Westminster system is based on convention and ambiguity and not rigid rules and clarity, the same Westminster system could be adopted and manipulated to produce diverse results and reactions that would shape their countries forever. These states therefore became Eastminsters (Kumarasingham, 2013) that had clear institutional and political resemblances to Britain’s system, but with cultural and constitutional divergences from Westminster. Ceylon’s Eastminster distorted the institutions and conventions of the Westminster model and created five key deviations that also had long-term consequences for the island’s democracy. These were:

- Elite families and personalities dominating the system

- Heads of State actively involved in politics instead of being impartial figures

- Manipulation of constitutional conventions

- Institutions and political issues governed by non-inclusive considerations and weak accountability mechanisms

- Executive power driven by the majoritarianism embedded in the system

I have argued elsewhere in greater detail about the consequences of this (see my A Political Legacy of the British Empire – Power and the Parliamentary System in Post Colonial India and Sri Lanka, London, 2013).

In this article I instead wish to address the potential abolition of the Executive Presidency and the return to a parliamentary model. Though the Dominion of Ceylon ended in 1972 and new systems sashayed on the island’s constitutional catwalk, Sri Lankans like their forebears retain a legitimate interest in the Westminster model and continue to debate and comprehend their politics using the Westminster lexicon. The opportunity before Sri Lanka is to learn the lessons of the past and create not just a ‘Soulbury Plus’ constitution, but an Eastminster more confident in its past, more wizened of its pitfalls, and more determined to create a just and lasting system rich in the experiences of its Commonwealth cousins and grounded in the conditions and aspirations of Sri Lanka. The same year that the Soulbury Commission was announced saw the end of World War II and the quest in Britain to build a New Jerusalem from the ashes of destruction and despair. Sri Lanka can now craft a New Eastminster seventy years later – a system both familiar and remote. Below are some key considerations to fashion the constitutional tools of any Sri Lankan Hephaestus in their mighty task to build a New Eastminster. The Commonwealth holds many precedents for this task.

The First XI

I. Head of State

Sri Lanka’s longest serving constitution is the present one, which gave the island an Executive Presidency. Seen by J.R. Jayewardene and many others, including his successors, as a panacea for Sri Lanka’s divisive politics and an office that could unite from above, it has instead turned to be more a placebo or worse in dealing with the state’s multiple maladies. Ideally a Westminster Head of State is an impartial and dignified figure placed to represent the best of the country and be guardian of its constitution. Critically the Head of State cannot have a party political role and has no constitutional powers to determine any policies, which are the purview of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Whether a Governor-General or non-Executive President, the Head of State (and the Executive) must have the Bagehotian triptych of rights vis-à-vis the Government: 1) The Right to be Consulted 2) The Right to Encourage and 3) The Right to Warn. This translates practically in having access to privileged information on the activities of the state such as Cabinet Minutes and diplomatic cables; regular and frank meetings with the Prime Minister – over hoppers perhaps as Soulbury and Senanayake did on Tuesday mornings – and other senior Cabinet Ministers and Public Servants where relevant; and have the ability to confidentially counsel the Government on all range of matters – though ultimately it is for the Government to take the final decision. All such meetings must be gazetted. In everyday politics the Head of State can expect to carry out mainly ceremonial duties such as hosting visiting foreign dignitaries, bestowing honours, and delivering speeches across the country. The Head of State must be a uniting and respected figure capable of successfully working with governments of all complexions. In times of crisss a Head of State may be called upon to exercise reserve powers such as withholding assent to controversial bills, ensuring the constitution is followed, dealing with unstable political conditions such as the death or resignation of the prime minister or unclear electoral results. Ultimately, however, an Eastminster Head of State, must only intervene in crisis situations, but otherwise leave the governance of the land to the politicians, whether they approve or disprove of their actions unless in contravenes either the law or the spirit of the constitution. Sri Lanka is no longer a Realm and thus a Head of State should be elected rather than selected. Ideally this election is not run on party lines and is conducted indirectly through the Houses of Parliament in combination with the Provinces as is done in India. Another method for the Head of State used in places like Papua New Guinea for the election of the Governor-General is a secret ballot of the parliamentarians. After serving as Head of State the individual should not expect to return or participate in active politics. A crucial role of the Head of State is their selection of the Head of Government, who must always hold the confidence of the popularly elected chamber and if this is not the case then the Head of State must either find another person who can or call new elections.

II. Prime Minister

In Britain and other Westminster Realms, Government is carried out in the Monarch’s name – hence the phrase Her Majesty’s Government. The Prime Minister derives power from being able to exercise authority as the Sovereign’s sole responsible adviser by virtue of commanding a majority in the House of Commons. This in turn means that the Prime Minister can utilise the formal powers vested in the Crown. In the Republics that follow the Westminster model the principle is the same. Prime Ministers ultimately have power by being able to count on a majority of the popularly elected chamber for support and thus ensure that the Government’s legislation can be passed. Prime Ministers are therefore beholden to Parliament and parties and not the Head of State for their survival and success. Whereas the Head of State is ‘above politics’, the Head of Government is the preeminent political leader in the country determining with the support of Cabinet and party or parties the government’s policy agenda. Almost always a Prime Minister is also the leader of the strongest party in the lower house. Unchecked a Prime Minister can personify what Lord Hailsham described as an ‘Elective Dictatorship’. Earlier incarnations of Eastminster Prime Ministers across Asia did that and more. A political vacuum was created at the end of colonial rule and more often than not Prime Ministers filled the gap. Too often not only were South Asian Prime Ministers concentrated with awesome power, but the electorate, Ministers and parties expected nothing less. This trait allowed democratic institutions to decay. A New Eastminster Prime Minister must not only be empowered to take key political decisions, but also constrained to act within the conventions of office and the requirements of the constitution. The other institutions must assert horizontal accountability on the Executive. For this objective to succeed the other institutions and the citizenry must be aware of their role, strength and duty. The Prime Minister in the Soulbury Constitution was also adorned with the Defence and External Affairs portfolios. Prime Ministers should not be burdened with other major portfolios since this can only centralise power in one person when instead power and responsibility should be shared more equally across the Cabinet. There are few post-war examples of Prime Ministers having other substantial ministries and even Margaret Thatcher could not be both Chancellor and Prime Minister.

III. Cabinet

The Cabinet is the apex of decision-making in the Westminster system. Theoretically the Prime Minister is only primus inter pares and senior Cabinet Ministers such as Finance, Internal or Foreign Ministers have exerted real power. A look at the Blair years shows that Gordon Brown as Chancellor of the Exchequer exerted massive power and effectively ran vast swathes of domestic and economic policy, which the Prime Minister could only agree to. More generally Cabinet Ministers effectively initiate programmes and hold considerable autonomy within their portfolio. The ministerial responsibility conventions means that Ministers are accountable for all the activities of their ministries and public servants. At Cabinet all Ministers have the opportunity to discuss, defend and destroy all policies subject to the collective will of the Cabinet, as interpreted by the chair, the Prime Minister. Once decisions are taken the Cabinet is bound by the convention of collective responsibility, meaning that whatever personal view or even opposition, all Ministers must abide by the decision. Historically, Eastminster Cabinets have been near pathetic in the observance of such conventions. Cabinet was more likely a den of nepotism or a seraglio of sycophants. Rather than forming a collective decision making body tasked with governing the whole country, Cabinet was more often a place of conspicuous patronage and unforgivable clientelism. Self-interest and power accumulation were instead the governing conventions. Political parties in Sri Lanka still revolve around personalities and not policies and at the Cabinet level Ministers either make their ministry into a fiefdom or allow the Prime Minister or President to run their portfolio from their offices. The result from this dereliction of constitutional norms and brazen abuse were threadbare standards of governance. Reforms from other Westminster states including recently the United Kingdom have instituted a strict Cabinet Manual that outlines the procedures and rules of the Cabinet and, though not a binding rule-book, any breach can be used as grounds for dismissal. The Manual also lists instances where a conflict of interest could occur; their duties; and also the constitutional conventions so Ministers know clearly what is expected of them. Since 1945 there has been a greater frequency across the Commonwealth of coalition governments, resulting from the demise of two-party or single-party systems. India, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and now the United Kingdom have experience of coalition and minority governments as well as single-party ones. On such occasions there is usually an agreement that determines the conditions for supporting the Government’s programme, usually revolving around policy concessions or ministerial appointments. It should, however, be clearly stated that such coalition agreements across the Commonwealth do not allow the intolerable practice as seen in Sri Lanka where regardless of which party is in government, certain individuals survive at the Cabinet table since they change their allegiance as easily as their hair colour. This lizard-like ability of the shameless to shed their party skin and possibly back again for pure self-interest can be restricted by appropriate rules in a Cabinet Manual, by Standing Orders of Parliament regulating crossovers, and even by legislation (as in India).

IV. Senate

The Soulbury Commission recommendation of an upper house was one of the few ‘traditional’ Westminster features that the Ceylonese Board of Ministers was not keen on. In some respects their concerns of the upper house never eventuated because the Ceylon Senate never, even lightly, tread on the ambitions of the Executive or House of Representatives, and few mourned its passing in 1972. Upper houses are a natural institutional feature in Westminster states such as the United Kingdom, India, Malaysia, Jamaica, South Africa or Canada. To be effective Westminster upper houses need to have a purpose, but not challenge the supremacy of the lower house. A conventional purpose for upper houses is to offer a chamber to soberly assess and improve legislation. In Westminster states, which have devolved provinces or other historic or ethnic regions, the upper house is often the chamber that provides a key representative function and thus fulfils a unifying institutional purpose for the regions. Membership of the Senate would provide an avenue to represent groups not normally able or willing to gain a place through the general electorate. Institutional membership can be provided – for certain religious, professional and minority groups as seen in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Many upper houses like the House of Lords or the Canadian Senate have a membership that is mainly nominated. The Australian and Indian upper houses are elected by proportional systems in contrast to their lower houses to encourage different groups and opinions to be selected. A combination of proportional election and appointment on the basis of adding value to Parliament provides a worthwhile compromise. In plural societies like Sri Lanka, a Senate ideally provides an invaluable home for various views from across the country – sectional and political – to participate at the centre without festering at being excluded from its politics, and crucially, not breaking the primacy and efficacy of the lower house.

V. House of Representatives

The House of Representatives of Ceylon, unlike its early legislative predecessors, rejected communal representation. The principle that all were Ceylonese justified this position. The sentiments may have been real, but it clearly was not realised. Almost all Westminster states’ lower houses have first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral systems. A slightly modified and improved version of this is the Preferential Voting system used for the Australian House of Representatives since 1918. This system asks the voter to rank all the candidates in their electorate in order of preference. If no candidate gains an absolute majority then the lowest ranked candidate is excluded and their votes transferred on the basis of their second preference. This process continues until a candidate emerges who has the support of over half the votes cast. This adjustment to the FPTP system enables the voter more likely to have someone selected that was in their top preferences – an alteration of this could allow for multi-member constituencies in diverse and heavily populated regions like Colombo that would see the top preferences elected to the House. Perhaps even more important is the electoral map of Sri Lanka, which would need to be rethought and redrawn to enable the key groups that inhabit the island the ability to be represented without recourse to communal or list seats. The electoral boundaries would be administered and reviewed by an independent Delimitation Commission. In concert with the Senate it is critical that Sri Lanka’s eternal plurality be represented and contribute to the governance of the island collectively, and not evade it due to the redundancy of being marginalised or resort to the ethnic outbidding that has characterised Sri Lankan politics thus far, where parties have little incentive or inclination of engaging with other communities. For the Legislature to function credibly the parties also need to be reformed. Parties need higher transparency, detailed policy forums and robust debate contained within a structured arena in preference to the kindergarten of shrill kleptomaniacs and superfluous sons following a flawed deity that is presently favoured. For the House of Representatives to act properly Parliament must regain its centrality to debate and ability to hold the Executive to account. The Executive needs be reminded that governments are ultimately formed and broken on the floor of the House of Representatives. Without a majority of members in support, legislation cannot pass and if this remains the case of key votes such a Vote of No Confidence the government must resign. Parliamentary rules would need to be strictly studied and administered. Such rules can be set by a Business Committee of all the leaders of the parties headed by the Speaker that can collectively agree to rules, which all parties must abide by, and create a consensus around a workable timetable for parliamentary business. The House must also have great ‘set-piece’ debates on crucial issues such as the Budget, Foreign Affairs and Constitutional issues, which all the parties have the right to address in addition to the crucial ‘Speech from the Throne’ – the Government’s annual programme. The Speaker on receipt of a deputation of MPs should have the ability to convene Parliament and thus remove the Executive’s otherwise exclusive power to determine when the House sits. Most prominently a robust Question Time session every week the House sits is essential for the Opposition and even backbench MPs to place hard questions to the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and supplementary questions without advance notice on current policy. This is a common practice seen in almost all Westminster states and where the Prime Minister should be made to sweat, not swagger. There has been considerable discussion on the worth of referenda. Historically and traditionally referenda have been seen as foreign to the Westminster model since it strikes at the concept that parliament alone can vote on the policies of the state. In recent years this belief has softened, but referenda are still used sparingly and only in limited contexts with specified impact, such as constitutional change. In New Zealand, for example, a referendum can be initiated by both the government and citizens (if able to register a specified proportion of eligible voters), but in both instances, referenda have only indicative value in that the state is not bound by the result. This mechanism holds that citizens can compel their representatives to hear their concerns, but also allow the government to reject or qualify the result since the state has responsibility for all citizens not just a majority of them, which referenda often represent. Referenda are strictly run by the Electoral Commission and are almost always held simultaneously with general elections.

VI. Committee System

Considerable academic and parliamentary views argue that the Executive is overshadowing Parliament, which is reduced to a mild inconvenience to be humoured as one of the stage props of a democracy. Critical reforms have taken place since the 1980s and have gained significantly in recent years in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand where Parliament has reasserted itself through Select Committees. These Committees unlike those of the Donoughmore era are not mere administrative appendages for Ministers to patronise. Instead they are designed to scrutinise the Executive and investigate issues of public concern. Formed solely of parliamentarians not holding Government office and reflecting the political composition of the Legislature these Select Committees covering all manner of subjects are able to choose their inquiries, investigate their subjects and harry their targets. To be a Chair of one of these Committees is sometimes more influential and more rewarding than Cabinet office. The best committees contain members of all political persuasions that are expert in their Committee’s field and enjoy wide spread support – very often Committee Chairs even come from the Opposition or dissident Government backbenchers. High profile committee hearings are the result of bringing in senior Ministers, bureaucrats, business leaders and others into their sights for a media drenched grilling. Such Committees have the ability, which the whole House does not, of probing in detail critical issues of public interest and compelling either through standing orders or public expectation answers from those who should have them. Such a revival has also generated greater interest from the public who are near invariably welcome to attend all Committee sittings and view their proceedings in print or online. There should also be options of joint committees of both Houses, and of course the Senate, less concerned with whipped party politics, may convene its own committees and produce its own reports. Select Committees are not a place of party populism, but instead an arena for cross-party consensus and meaningful investigation.

VII. Judiciary

Traditionally the Queen-in-Parliament is viewed as completely sovereign in the Westminster model – theoretically able to make or unmake law on any matter. The judiciary have the duty under this system to interpret those laws and with the weight of precedent from common and traditional laws. Judges in the system must be fearless in their application of the law and be oblivious to political or personal bias or pressure. Therefore the judicial branch must have the ability to frustrate the will of the Executive if there are legal grounds to do so. A strong judiciary is jealous of its independence and preserves its integrity. Judges keep strictly separate of the Executive and Legislature and intrepidly uphold the constitution when it is under threat whether from president or peon. For such a judiciary to exist judges must feel confident in their position and duty, which means all temptations to follow or whither from Executive instruction must be removed. Clearly many at the highest levels of the Sri Lankan judiciary have not functioned anywhere near the expectations of the law and have ignored their oath of office. Statutory and constitutional safeguards must be in place to protect the judiciary’s role and cordon it administratively by providing ample resources to carry out its demanding task without calling upon the other branches of state for sustenance or favour. It must also work the other way. Judges must be personally and professionally removed from any political or financial avarice and be legally reprimanded and removed if such temptations arise. In many Commonwealth countries judicial expertise is very often shared either at a regional level like the Caribbean Court of Justice or internationally like the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which remains the highest appellate court for multiple countries. The shared legal heritage has also enabled countless senior judges to sit on the bench of the other Commonwealth states including the Sri Lankan jurist L. M. D. de Silva who served in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. Though it is unlikely Colombo would restore appeals to the Privy Council, it would be highly commendable and beneficial to draw upon the Commonwealth to make appointments to the Sri Lankan Supreme Court. The provision of one or more Commonwealth justices on the Sri Lankan bench would increase the scope, impartiality and knowledge available to the court and embed a necessary aloofness from the Executive. The Asian region itself has a vast reservoir of judicial experience in dealing with issues highly comparable to Sri Lanka’s. Malaysia called upon legal experts from Scotland, England, Australia, India and Pakistan for its constitutional and judicial set-up while the Pacific, Africa and the Caribbean have long histories of judicial borrowing.

VIII. Public Service

A fundamental principle of the Westminster model and of the old Ceylon Civil Service was strict neutrality. Regardless of the party or minister a senior public servant’s responsibility was to serve the government of the day and implement their instructions within the bounds of the law after providing frank advice on the merits of the policy at hand and the constitutional context of the decision. The senior members such as the Permanent Secretaries to Ministries were generally those who had trained and worked their whole lives in the public service and mastered the ethos of a service that stays above politics. These principles apply equally to the Diplomatic and Armed Services. Civilian authority is entrenched and actions are carried out after providing free and frank advice and in respect of the law and constitution. Public servants are not, however, the mouthpiece of any political party and especially during overt political actions and periods, such as election time, must refrain from any action or appearance that can be perceived as politically partisan. A relatively recent innovation in many Westminster states is to have Special Advisers. These are political consultants appointed on the recommendation of individual ministers that provide open party-political advice in the minister’s office. Unlike public servants their job is tied to the individual minister and they are not retained in changes of government or minister. They are not given access to all confidential files and they have established boundaries on what they can and cannot do. This innovation has arguably allowed ministers to receive important and necessary political advice and at the same time insulated ‘permanent’ public servants from taking on political tasks. Another innovation seen in some Commonwealth states is the office of ombudsmen for various sectors such as banking, law, education, freedom of information, etc. Whereas public servants are mostly and necessarily anonymous to citizens the Ombudsmen’s office is to provide the public with an avenue to lay their grievances or perceived injustices on public services. The Ombudsmen have the power to investigate these claims and compel a response from the appropriate ministry. Freedom of information is also a relatively new and critical right for all citizens. This makes the publication of specified information mandatory from all Ministries and gives mechanisms for citizens to request information, which if denied, must be justified on legal grounds. This provision has been powerful in promoting transparency and accountability from the Government and Public Service.

IX. Bill of Rights

For most of the countries that emerged from British rule and followed the Westminster system, including Sri Lanka, a Bill of Rights was viewed as an unnecessary legislative instrument to protect the rights of citizens. Events have proved otherwise to put it mildly. The Indian assertion of a chapter of fundamental rights in their republican constitution has proved a powerful symbol and tool to judge, defend and demand rights under the constitution for all types of groups and individuals including cases covering race, language, religion, caste, gender, sexual orientation, education, freedom of expression and quality of life. Even the traditional Westminster states of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom have all inserted strong legislative instruments against such discrimination that are routinely held justiciable and respected by all governments. Now such legislation is taken to be near mandatory. Beyond the law the symbolic inclusion of such Bills of Rights is the fact that it creates a culture of protection and empowerment that keeps a check on Governments by reminding them with the authority of the constitution that individual and group rights matter and will be enforced if threatened. In the historically plural environment of Sri Lanka where rights have been too easily malleable, this is not only desirable, but also essential. An adoption of such a legislative and legal regime fiercely maintained would also end credence to the criticism that Sri Lanka does not function under the Rule of Law and would normalise the country’s political and diplomatic relations beyond the rogues gallery of international outlaws.

X. Council of State

As will be noticed from previous politics in Sri Lanka personnel are critical for any system to work well, particularly one like an Eastminster where convention reigns and thus much is left to the interlocutor to determine. Historically, in England, even before the advent of constitutional monarchy, the Crown was advised and surrounded by a Privy Council. The body was powerful in its own right and even a determined Sovereign had to navigate the sensibilities and duties of the Council to succeed. This counsel extended to those of patronage and appointments. The modern Privy Council (the judicial body is merely a committee of the Council) is drawn of almost all serving and former high ranking Cabinet Ministers, Law Lords, Civil Servants, Prelates and select Commonwealth Prime Ministers, including at one time D.S. Senanayake. The body no longer provides formal political advice to the Sovereign since this is the role of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. However, as mentioned above, within the Crown still reside awesome powers, which the Prime Minister in effect exercises for political benefit. The framers of the Indian constitution were worried about this and wanted instead a Council of State modelled on the Privy Council and Irish Council of State to aid and advise the (non-Executive) President on matters of national importance in decisions on which any party bias has to be avoided. The Council of State was proposed to consist of the Prime Minister, the Deputy Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of the Union, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the Chairman of the Senate, the Advocate-General, every ex-Prime Minister, every ex-Chief Justice and a limited number of other persons appointed by the President in his absolute discretion. Such a Council was advocated since it was thought useful in India in such matters as the protection of minorities, the supervision, discretion and control of elections, and the appointment of judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts. The idea was rejected, but has not been forgotten and similar ideas appear across the Commonwealth. The Canadians have their own Privy Council and leading scholars have advocated such a scheme for many Commonwealth countries including Australia and New Zealand. The Irish Council of State is composed of the Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, Chief Justice, President of the High Court, Presiding Officers of the two Houses of Parliament, Attorney-General, any former President, Prime Minister or Chief Justice willing to serve and up to seven presidential nominees. Such a membership with the inclusion of the statutory office of Leader of the Opposition could be used to scrutinise, debate and formally recommend candidates for major office such as Provincial Governors, appointed Senators, Permanent Secretaries, Armed Forces’ Chiefs, High Commissioners and Ambassadors, Commissions of Inquiry, Judicial Officers and other statutory public service positions such as the Delimitation Commission as well State Honours. In addition the Council could help with President’s major reserve powers:

- To appoint a Prime Minister

- To dismiss a Prime Minister

- To refuse to dissolve Parliament

- To force a dissolution of Parliament; and

- To refuse assent to legislation

These five powers are all, or at least can be if the situation is not clear, controversial and critical powers. However, a non-Executive President in such situations where the decision is far from obvious or where he or she is unsure as to the validity of the choice is compelled to make decisions with minimal opportunity for consultation. The Council of State could act as an ‘integrity branch’made up of the highest practitioners from the three branches of state and chaired by the President. Such a body may well prevent the predilections for equine selections by Sri Lanka’s Caligulas without drastically compromising the principles of a parliamentary state.

XI. State Structure

Historic Westminster literature held that a true Westminster state should be unitary. These accounts centred on Britain, but applied their mores to the rest of the Commonwealth. The reality is that most of the major Westminster states have varying degrees of formalised devolution or federalism. Canada, Australia, India, South Africa and Malaysia for example all follow this characteristic. Not only these states, but the United Kingdom itself has always had levels of devolution – Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all retained distinct ‘national’ identities, and institutional and policy features even before the establishment of parliaments in Edinburgh and Cardiff in 1999, while Northern Ireland’s parliament can be traced back to 1921. All of the above Commonwealth states have federal features, but also unquestionably have powerful centres and rarely describe themselves as federal. There is nothing contradictory about this. It is, like most Westminster principles, based on pragmatic considerations and justly acknowledges certain degrees of autonomy due to a combination of historical, cultural, religious, linguistic and ethnic reasons while at the same maintaining cooperation and territorial unity. Secessionism is not an option, but nor is blanket imposition of central policy that affects the rights and identity of a significant portion of the country. Rather than lead to disintegration or civil war the federal structures of Canada, Australia and India have instead secured unity and also accommodate various groups by giving powers in certain spheres. The Eastminster parliamentary state structure therefore provides provinces with meaningful powers and agreed levels of autonomy on certain questions, and a simultaneous acceptance of the Centre’s powers and national jurisdiction on all other matters. This structure creates two major levels of government. Firstly, the national level where politicians represent their constituency in the House of Representatives and their Province or group in the Senate that together forms the National Legislature. The second level is at the provincial level and the structure of the Centre is usually replicated in the Province, but in a unicameral legislature where the Government is headed by a Chief Minister and a Governor formally heads the Province as the President’s (not the national Government’s) representative. Such a framework would mirror the styles and practices of states such Australia, Canada and India where an agreed list of powers for both Centre and Province are entrenched.

Conclusion

Many readers will note that several of the reforms above have been heard before and some are highly similar to those suggested in the proposed Nineteenth Amendment while others such as the Seventeenth Amendment need only be implemented to provide a Constitutional Council approximate to the above (X) Council of State. However so much has been warped by the Executive Presidency and any reform suggested from within or around it is still likely to be acculturated by it, which is not a boon for a state seeking to foster consensus and cooperation. The Eastminster First XI seeks instead to draw on the hopes of independent Ceylon, which was once seen as the ‘Best Bet in Asia’ and remove the resilient chaff of ‘Great Man’ messiah worship inherent to the Executive Presidency, to reveal a more participatory and inclusive structure that the parliamentary system provides. The Eastminster First XI also spurns any wistful nostalgia for another era and rejects the need to follow to the letter another country’s system. Instead as Eastminster implies it implores the country to be aware of its past Westminster heritage and Commonwealth constitutional developments above and select the best to be forged with Sri Lankan needs and beliefs. Cleary this exercise is worthless without people. As Dr B.R. Ambedkar said when introducing the draft Indian Constitution, “if things go wrong under the new Constitution, the reason will not be that we had a bad Constitution. What we will have to say is that Man is vile.” The Soulbury Report did not quote the entire sentence of Molière’s reproduced at the beginning of this piece. The sentence ends “vous avez justement ce que vous méritez [you got exactly what you deserve]”. At the very least all Sri Lankans deserve better than what they have had.