Photo courtesy of The Carthaginian Solution

In the precolonial period of country’s long history, much of organised life was impacted from inter kingdom wars, natural events, harsh climate, hierarchical attitude and behaviour of provincial rulers, and the demands from the broader native population for services and a part of what they produced in return for their ability to use land for living. It was a deeply unequal society and the inequality was maintained by the deployment of caste system within which some individuals and families were considered as superior and others inferior. What rights and freedoms did the larger population – not involved with the royal administration or belonged to higher caste/s – was able to access have not been examined well.

Even the historians who compiled our ancient and medieval history concentrated on the royal history rather than the histories of common people or to use a postcolonial term subaltern voices. Although this system has not been studied by Sri Lankan historians, anthropologists and scholars to its full extent, the field provides fertile ground for producing further scholarly work to understand the divide between rulers and the ruled, how it was sustained and its impact on the masses of people who did not belong to nobility.

Material and symbolic distance between the two types of people and justification of unequal existence was so great that the incorporation of some natives into the administration in low levels as subordinates and provision of a symbolic explanation to justify the lower level of life available to them and public consumption was a key feature of the precolonial political and social order. This was provided by religion, mythology, ritual and sorcery. Mainly the suffering of people was explained as something due to their own actions, past and present, and the only way that they can seek salvation was described as through embracing religious activities and seeking a good life in the next birth. Socio-economic and power inequalities that existed were viewed and interpreted as there to stay. The larger population was encouraged to accept what existed and move on with life as simple as possible. Elaborate ceremonies were kept for the nobility – political and religious – to celebrate power and privilege.

According to historian Michael Roberts, in Sinhale, “Surplus appropriation sustained both Sangha and the ruling aristocracy. These appropriations involved labour services as well as goods and money. The tenurial, caste and exchange systems were crosshatched. These patterns of authority were sustained by administrative officials directed by the king…These economic relations and the practices sustaining the appropriation of surplus were girded and threaded by cosmological conceptions. Supernatural forces were attributed with power. They were feared, mobilised, cursed and manipulated. In this society ritual was pragmatics, a work. In the result there was a diverse host of ritual specialists. The king was the grand-daddy of all the ritualists. His righteousness and the ceremonies around his sacred person were central to fertility, potency and the favour of the greatest gods like a Chakravarty figure.”

Some post-independent political leaders assumed such a role especially after the creation of an executive president position to govern the country with unlimited power, symbolism, ceremony, stately ritual and distance from the average Sri Lankan subjects whose worship of the powerful figure was expected after becoming the pseudo king.

The unequal social order was maintained by a) the land tenure system b) royal rivalry, war and rhetoric c) caste system and d) symbolic representation of royal and religious privilege. Scholarly work on each of these by Sri Lankan and foreign writers show that they did not examine them in terms of inequalities that they created and maintained but each of these phenomena as separate and insular ones with internal dynamics. Resistance to the system was not well recorded except perhaps in terms of some creative works such as Sandesa Kavi, literature and rituals. Lack of a voice for those who occupied the lower strata of society, majority of the population, contributed to this.

Notwithstanding the issues in social relations (political, economic, cultural), in good times the system allowed for progress in agricultural, trade, cultural fields including scholarship. International relations and the absorption of immigrants from other countries to the system of governance and lifeworld have also been a notable feature.The presence of different ethnic communities other than the Sinhalese reflect this phenomenon. Live and let live seems to have been the governing philosophy. However, those who engaged in criminal activities were punished with harsh measures. The king and his court officials listened to people’s grievances in an orderly manner. If justice was not provided through such measures, aggrieved parties sought the intervention of divine powers through religion and ritual. Buddhism became a religion to meet such expectations from the public. By the time European colonisation started, the island had been divided into three kingdoms and due to inter kingdom wars and limited resources, social disorganisation had set in place. Entry of European colonialists added an extra layer to the complexities that the Kingdoms had to deal with. Yet being a country depending on trade, kingdoms were interested in exchange relations with foreign traders. In later years, Sinhalese kings sought the assistance of foreign colonial powers to defeat the one came before.

Colonisation and its impact on society and its organisation

Colonisation of the island by European powers introduced changes to the pre-existing hierarchical set up as well as the socio-economic and political organisation in a substantial way where the common people presumably had few rights and freedoms compared to the ruling families both at the centre and provinces. Without understanding social transformation (including economic, political, cultural and educational) that took place during the European colonisation of the island, it is not possible to properly comprehend why Sri Lanka descended into where we are today because the transformation was multidimensional, deep rooted and externally led.

Writing about the British colonisation of Ceylon, Yasmin Gooneratne states, “The vision of the island as a fair (or hitherto barren) field or garden, in which the seeds of Western ideas are to be sown, occurs frequently in the English writing of the period, and not only in that of Civil Servants….The vitality and power of political ideals, and of the images in which they found their natural expression, helped to obliterate almost entirely (as far as literature was concerned) the militarism and the commercial exploitation that colonialism countenanced in the 19th century. E.g., planters were thought of as benevolent philanthropists.”

Commenting on the nature of history written, she further states that, “The histories of Ceylon written in the period interpreted Ceylon history according to attitudes and ideas current at the time in Britain, and were in some cases aimed at a Ceylonese reading public, whose outlook and opinions they were intended to mould”. She refers to a young historian called William Knighton and reminds us the way he “challenged the right of English historians to judge the East by the inadequate and irrelevant standards of Western civilization; and was even prepared to claim that a cultivated and unbiased mind would concede to Ceylon honour similar to that it paid to the civilisations of Greece and Rome”. But the domination unleased by military occupation of Ceylon by the British and subsequent rule by using political, cultural and normative ideas imported from Britain was of a different kind. Subtle means used to maintain such domination over the inhabitants of Ceylon set the new rulers apart from those who preceded them in kingdom times.

One approach we can take to discuss the impact of colonisation on the native population is to look at the winners and losers. There were some who benefitted from the colonial and imperial project materially while imitating the manners of colonialists and those who did not receive benefits. Instead, many lost what they had e.g., those who lost land. Those who spoke truth to colonial power was rare and they emerged in the late colonial period after acquiring the lingua and other elements of the colonial culture through education, work, association and servitude. Who were the winners?

Historian S. Arasaratnam provides an account of the administration during the Dutch period and those natives who held important positions under the Dutch rulers. According to him, “Beneath the superstructure of Dutch Officialdom was the native administrative system which was assimilated by the Dutch….There was the traditional system that had existed under the indigenous Kingdoms and had remained intact at least at the provincial and village level till the coming of the Dutch”. The Dutch maintained traditional division of each Dissavani into Korales and Pattus. The Mudaliyars, Koral and Attu-korale were the chief administrative officials. For the day to day management of villages affairs there was Vidanes e.g., supply of labour for various cultivations or construction work.

A. Raffel describes the changes that took place with the British rule starting in 1815 as follows: “Ever since 1815 when Ceylon came under total British rule, the customs and manners of the British including the widespread use of the English language took a dominant hold of the country. The language of administration, teaching in schools, were in English and social customs took a western oriented dominance. Although such circumstances did suffocate the development of indigenous culture especially the growth of social and religious activities and practices, there were elements of the local population who by reason of association with the British, or through their own entrepreneurial skills reached a level of near parity with the colonialists. Subsequent governmental policies and social pressures over the years have changed the fortunes of this class and are mostly obliterated from the nation’s psyche.”

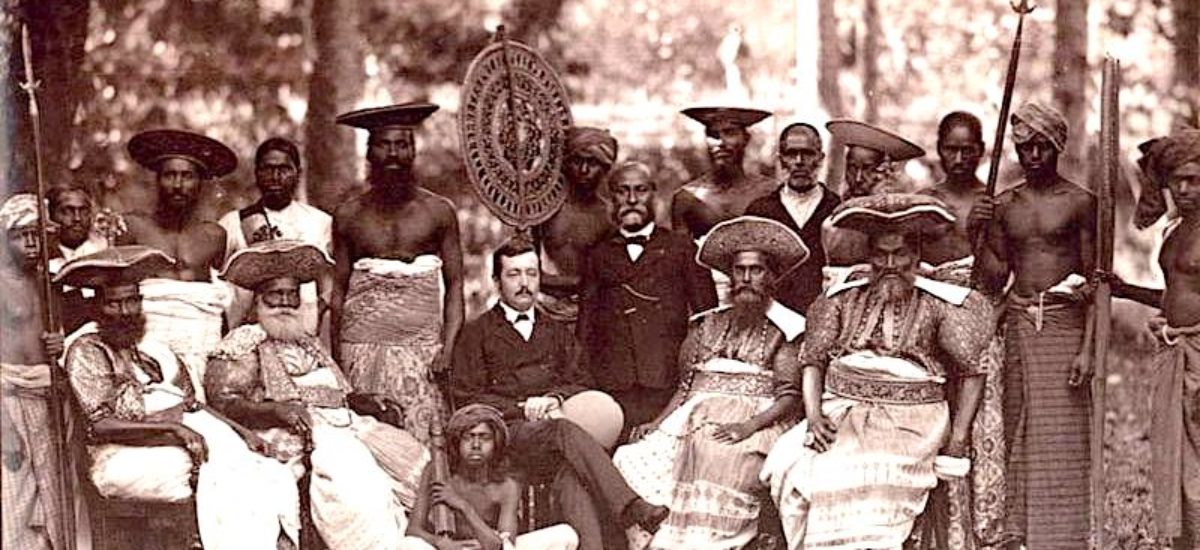

British colonial administrators co-opted respectable Ceylonese with a family genealogy or service to colonial administrations as native chiefs into their administration both at the national and provincial levels. We can’t find many historical profiles or critical examinations on the way such native chiefs assisted colonial administrators to keep the masses under control or the struggles of native population who sought justice because of the inclination of historians to focus on the rulers rather than the ruled and explain the new methods of governance as benign events leading to a degree of democratisation and self-rule (white washing). The Chieftains of Ceylon by J.C. Van Sanden provides details of various categories of chieftains. In the administration included were those who worked in the courts, police, government service, armed forces, health service, agricultural and irrigation services, survey and archaeological department, education and higher education and more. Those who were employed in such service provision also benefited from the colonial administration as they were able to draw a regular salary and other benefits such as foreign training, leave and travel. Expansion of urban centres including Colombo as a commercial centre including a port was a key factor in the colonial rule and associated changes. The Great Rebellion of 1818 by Tennakoon Vimalananda provides insights about those chieftains who collaborated with the British and the manner the latter took steps to curb any further resistance. Correspondence between the governor and colonial secretary is revealing.

In addition to the native chiefs, others benefited from the expansion of colonial rule to countryside and opening of the countryside in the outlying districts to tea and rubber plantations. Urban centres were opened for trade and commerce. Prior to the establishment of British rule, spice trade had been developed especially in the Kandyan areas. Later, Kandy itself developed as a centre of trade and commerce. Some residents in the low country migrated to Kandyan areas including Nuwara Eliya and Badulla in search of work in construction, trading opportunities, and so on and settled. Some married women with means. Muslim and Tamil traders also benefited from this changing context.

Those who were able to achieve an English education, convert to christianity or catholicism and assimilate to the colonial administration and its values, dictates and expectations by playing major roles like mudaliyars, court or police officials, professionals, academics, public servants or even superintendents in tea and rubber plantations while displaying unquestioned loyalty to the king or queen accessed many privileges offered by the new rulers. They in fact became a class of its own among the natives. They and their family members became capable of speaking the colonial language, imitate their manners and attitudes, housing and dress styles, employing domestic staff and those who worked their land as servants.

Those who made their fortunes in the trade and commerce including import-export sector also attempted to follow patterns of behaviour and attitudes described above with some success. Consumption patterns of this class also reflected use of imported goods, food and medicine as well as culinary practices. Introduction of tea to the country actually erased many popular local fruit and herbal drinks. Until recently about 20 such traditional drinks could be observed among street hawkers in Kandy. Western medicine and medical practice assumed superiority. In the education and higher education Western knowledge assumed superiority. Obtaining a degree or professional qualification from England became a sign of new status, recognition and even pretentions. Traditional methods of teaching and learning started to decline due to the lack of state patronage (this will be a subject of a separate article later). In the latter part of the British rule, some Ceylonese entered the political field and the State council through elections limited to individuals with certain characteristics desired by the colonial rulers. Women were not included.

A new identity giving superior status to an emerging upper and upper middle class compared to the native population who did not have access to English education, training or colonial power centres among the Sinhalese, Tamil or Muslim communities became a reality. Members of this class acted as brokers between the colonial rulers on one hand and the native population on the other. The way they looked at their own people or their attitudes and behaviour patterns resembled to that adopted by colonial rulers and their associated in the business and commerce sectors. Yet many of them were distanced from the larger society. This is a broad generalisation on my part as some of the native chiefs or professionals who benefited from the colonial administration and associated services maintained good relations with Buddhist monks or Ayurvedic physicians etc even while performing their duties for the colonial rulers. However, a class system was implanted among the native population with those close to the colonial power and those without.

According to Michael Roberts, “The rise of the local middle class interlaced with capitalist modernization in the 19th century-and-thereafter, with the British road/rail transport network and the expansion of coffee plantations in the Central Highlands forming the keystones for economic growth and exploitation. The British also instituted a new bureaucratic order, one integral to the state form that was being moulded in Europe at the same stage. English was the media of state administration. Able to pick up English quickly and located in key urban centres, the small Burgher population profited from the channels of educational advancement that opened up in the 19th century and filled intermediary roles in the administration, while also providing a significant number of schoolteachers in towns. Education brought the intellectual currents of Europe to the small corpus constituted by the English-proficient middle class in the early-mid 19th century.”

Referring to the gentry-class and others, he says, “The use of kärapotta and kärapotu lansi as pejoratives is placed alongside a whole battery of epithets in the Sinhala-world which depicted the invading forces from Europe and abroad from the sixteenth century onwards: notably, parangi and tuppahi…..It was a weapon of the underprivileged (Sinhala) classes because it was also a response to the widespread tendency among the emerging middle classes in British Ceylon, whether Sinhala, Burgher or other, to depict the rural masses as yakoes and godayās (that is, rustics without knowledge – meaning English-media knowledge).

“The Britons in Ceylon were stratified. The gentry-class made up of the Civil Servants and other public servants, the leading businessmen and planters kept aloof from the petty functionaries such as the shop assistants (called “shoppies”) at places in Cargills and the railway drivers. The Burghers themselves were sharply divided in the 19th century – with the differentiation being imprinted in the terminology “front door Burghers” and “back door Burghers”. Both in English and Sinhalese this line of class difference was embodied in the distinction between the respectable “Lansi” and, supposedly, the not-so-respectable “Tupass.” Furthermore, there was a “widespread tendency among the emerging middle classes in British Ceylon, whether Sinhala, Burgher or other, to depict the rural masses as yakoes and godayās (that is, rustics without knowledge – meaning English-media knowledge)”.

Read Part 1 here: https://groundviews.org/2023/09/05/why-sri-lanka-has-descended-into-chaos-and-the-way-forward-part-1/