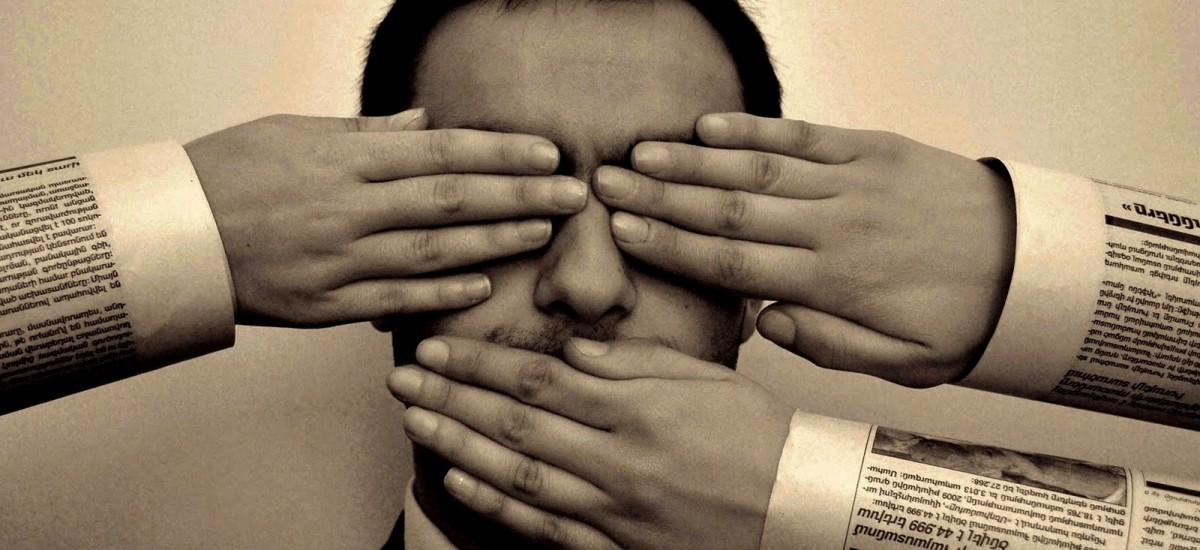

Image courtesy News First

‘We were anonymous, and even then I had the sense that cities were yielding; that they moved over and made room.’

― Sheridan Hay, The Secret of Lost Things

They are often warned that no conversation on reform in Sri Lanka is worth having unless had in the vernacular of the masses. They are constantly reminded that they are irrelevant. They are treated as non-entities in ideological warfare. The media seldom makes reference to them, while nationalists and hardliners make headlines. So they grieve amongst themselves in their anonymity, trapped within their walls of reason, surrounded by bigots and extremists. They believe change is impossible unless others change their minds. Their belief in their collective irrelevance is their opiate. Defeated, they lull themselves into quiet conformity and convince themselves that they must dine with wolves in order to survive. In the process, they are reduced to parochial sheep; sheep adorned in wolves’ clothing to avoid detection. An existential crisis confronts them—those of the City—today.

By ‘City’ I do not mean the elite class. The City is neither a geographic nor physical space located in some urban setting. It does not exclude those from rural or suburban areas. It is neither a Western nor an Eastern ideal. The paradox of the City is inclusion amidst anonymity. People of similar leanings congregate in cities, yet remain strangers. It is the only place that one could feel alone amidst a crowd. It is thus my euphemism for the space in which the dwindling ideology of liberalism resides in this country. The City is where we liberals reside.

In this piece, I will attempt to examine recent developments in the City—from its decline in political influence to its surrender to political patronage. I will nevertheless point to a critical opportunity. The smog of war that once clouded our judgement has—perhaps for the first time in five years—dissipated. An international justice project now serves to magnify the country’s problems, compelling introspection and course correction. A moment of clarity has arrived. If ever there were a moment in which the City might launch a new ideological battle, it would be this moment, now.

The Decline of Public Reason

Past leaders heard and grappled with our views. Admittedly, our views went unheeded, as we often fought losing battles. Time and again, our leaders exploited the fundamental weakness of any democracy—its susceptibility to majoritarianism. We watched helplessly as they appealed to the emotions, fears, prejudices, and ignorance of the masses in order to gain and maintain power. They rendered an entire community stateless overnight; discriminated countless Tamil-speaking public servants; and brutally suppressed peaceful protests. We spoke out too softly against those early injustices. Yet our voice grew louder over the decades. We spoke out more clearly against blanket emergency.[1] We cautioned against the constitutional grant of ‘foremost place’ to any one religion.[2] Despite sustained demagogy, a voice of public reason was slowly crystallising. Yet we perhaps lacked the conviction of empathy. The illusion that leaders still identified with our values insured us that we ourselves were somehow immune to oppression. A line was then drawn in 1983, when the mob tore the City apart at the beckoning of those very leaders. We were not spared if we fell on the wrong side of the ethnic divide. Our smug sense of security was laid bare as flames of hatred engulfed our dwellings. Make no mistake; many of us daringly protected victims. Even today we habitually recall our heroics. Yet, in the end, we lacked the fortitude to protest the injustice and prevent escalation.

During the war, we often failed to observe the compromise of our values, particularly when leaders adopted illiberal policies in our name. As victims of terror, we afforded them the latitude to oppress on our behalf. We too were governed by emotions, fears, prejudices, and ignorance. The language of terror soon replaced the language of reason. While we struggled to understand the extent of our decline during previous eras, nearly a decade of this regime’s rule laid all doubts to rest. We were now a City besieged.

The price of our dwindling political influence is the decline of public reason. Hark back to the casual promulgation of the Eighteenth Amendment or the crude impeachment of the Chief Justice. On each occasion, the unreasonable juggernaut forged ahead with impunity while the voices of reason were reduced to murmurs. We are now left with a fundamentally unreasonable discourse, where rhetoric and propaganda are sufficient to convince, and rational debate ridiculed.

Post-war Privilege

The City’s post-war history has not been all grey. In fact, much of it has been shimmering white, with carefully placed spotlights to highlight its glamorous contours. The pristine streets, the restored sites, the very buzz of progress heard in the restaurants and courtyards undoubtedly delight us. We are enamoured by the new splendour of our surroundings, made possible only by the ‘peace’ secured by the present regime. We occasionally quip that the warmongers have been vindicated. We even feel entitled to the spoils of war, as we too suffered egregious violence.

The price of this ‘peace’ is patronage. The City is this regime’s new client. Despite the decline of our political voice, the new economic dispensation affords us unprecedented levels of luxury. And thus we are kept happy—our minds eased from the burden of reasoning. In an act of calculated ‘benevolence’ we are afforded the space to live our liberal way of life; provided we pay the right tribute—our silence and our cooperation. The temptation to abandon lofty ideals in favour of real comfort and convenience is therefore irresistible.

The City’s transformation into a symbol of apathy and decadence tempts us to abandon the liberal project altogether. We no longer seem to hold the keys to our own City. Our hypocrisies and contradictions mock us. The very reference to the ‘City’ invokes scorn and cynicism amongst the few still genuinely committed to fighting injustice and corruption. Yet our predicament grates against our conscience. There is still a hint of frustration that sets us apart. We know there is no cure for our concealed depression, except a radical reordering of our society. We remain uncomfortable in the knowledge that we enjoy privilege, and not power. For we wish to be the masters of our fate rather than privileged sheep amongst wolves.

A Moment of Clarity

For decades, the state controlled the content and dissemination of information in Sri Lanka. Despite our ability to question and to critique, we happily accepted a version of the truth that was comforting and convenient. Even after the war, we watched with vacant expression as alternative voices in the media—voices of dissent—were systematically eliminated. We needed a catalyst to stir us from our reverie—to compel us to confront reality.

In March 2014, the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted the third in a series of resolutions on Sri Lanka.[3] The resolution calls for the implementation of the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendations. More than two years have lapsed since the government-appointed Commission published its report in December 2011. Yet the government has fully implemented only a handful of these recommendations.[4] The resolution also points to ongoing problems in the South, including religious violence and military attacks on civilians. These problems are symptoms of impunity cultured by our silence and cooperation. A Damocles’ sword in the form of an international inquiry meanwhile hangs over the government should it fail to correct the course.

Two years ago, when the first resolution on Sri Lanka was adopted, Southern opposition to its contents was virtually unanimous. The reaction to the latest resolution, however, has been somewhat mixed. Sections of the Sinhalese press, which reaches more than 60 percent of the readership, adopted a distinctly pragmatic stance, calling for swift domestic reforms.[5] An extraordinary shift in the discourse is taking place. When confronted with sustained and compelling reasoning, the reasonable mind cannot help but begin to face reality. We begin to detect the irrationality in failing to implement the recommendations of homegrown mechanisms. We begin to acknowledge the cancerous nature of corruption, impunity and bigotry. Even if we had briefly abandoned our liberal values, we find it too awkward to ignore reason. In May 2009, many of us became intoxicated on the fumes of triumphalism. Five years on, we have awoken to an appalling hangover. Our throbbing conscience now beckons us to act.

The City is still too splintered to pose any resistance to the status quo. We have been too easily divided, distracted and conquered. All that unites us now is perhaps our quiet allegiance to reason. This is an important identity. It is an identity that is forged not by geography, ethnicity, religion or class but by attachment to values. It is an identity that is fundamentally inclusive rather than exclusive.

The City expands and contorts to make room for new inhabitants.

In this moment of clarity, our first steps in a long walk will be small. We must first preach amongst ourselves, the so-called converted, before preaching to the masses. We must slowly re-forge our identity. To forge this identity, we must self-identify with values such as freedom, equality, justice and tolerance, and speak with one compelling voice. To speak as one, we must come under one liberal banner—not one of political affiliation, but one of language. We must speak in one language—not Sinhalese, Tamil or English, but the language of reason. The more often and compellingly we speak, the more defined our identity will eventually become. We must then give leadership to a new struggle that is underpinned by our values; a struggle that fundamentally appeals to reason. We in this City must eventually draw public discourse into the realm of ideas, where we still retain the prowess to convince and influence. We must believe that we have the power to steer the course of this country. We are not irrelevant, and neither are our values.

[1] See Civil Rights Movement of Sri Lanka, Letter to the Hon. Sirimavo Banadarnaike, Prime Minister on the restoration of certain rights and liberties of the people suspended since the declaration of the State of Emergency in March 1971, dated 10December 1971, in the Civil Rights Movement of Sri Lanka, ‘Peoples Rights’ documents (1971-1978), at 21.

[2] See Benjamin Schonthal, ‘Buddhism and the Constitution: The Historiography and Postcolonial Politics of Section 6’ in Asanga Welikala (ed.), The Sri Lankan Republic at 40: Reflections on Constitutional History, Theory and Practice, Centre for Policy Alternatives (2012), 201-218, at 215-216.

[3] Resolution 25/1 titled ‘Promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka’ adopted at the 25th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in March 2014.

[4] See for example, Verité Research, Sri Lanka: LLRC Implementation Monitor – Statistical and Analytical Review No.2: Constructive Recommendations (March 2014). The report lists 179 actionable recommendations of which 105 recommendations fall into eight categories of ‘constructive recommendations’ listed in two previous UNHRC resolutions (19/2 and 22/1) on ‘Promoting Reconciliation and Accountability in Sri Lanka’. According to the report, only 5 of these 105 recommendations have been fully implemented.

[5] See Verité Research, The Media Analysis, March 17, 2014-March 23, 2014, Vol. 4, No.12 (March 2014), at 6.

###

This article is part of a larger collection of articles and content commemorating five years after the end of war in Sri Lanka. An introduction to this special edition by the Editor of Groundviews can be read here. This, and all other articles in the special edition, is published under a Creative Commons license that allows for republication with attribution.