Image courtesy Sri Lanka Brief

Introduction

Before the war, we were all together. Now, we are widows with no security, and no one sees what we have to live through. But we go on, try to find some money to get us through the day…we have to eat, no? The cooking and cleaning needs to be done, the children have to go to school…that’s how life goes.[1]

What must have seemed to 36-year old Rina[2] like nothing more than a statement of unavoidable realities is laden with meaning for social scientists studying representations in postwar contexts of‘vulnerability’ and ‘marginalisation’ – and perhaps even more interestingly, the meanings of‘survival’and‘endurance’ in such settings. Tragically, although an intriguing subject for study, Rina’s circumstances are relatively ‘ordinary’ in the north of Sri Lanka: she is one of the estimated 40,000 female heads of households (“FHHs”) in that region[3], most of them born from the three decades of civil war.

Given the oppressive environment of military surveillance and control over information which still persists in the north, as well as the historically polarized nature of Tamil-Sinhalese politics, impartial academic research into the needs and response strategies of groups thought to be vulnerable in this area is desperately needed in order to understand their ways of coping, and better meet their ‘real’ needs. Within this context, this article presents the findings of interviews conducted with 65 FHHs[4] in ten villages and towns in northern Sri Lanka in early 2012[5].

The main goal was to uncover the various ways in which FHHs have reacted to the most pervasive economic, physical and psycho-social vulnerabilities facing them in the postwar context. In doing so, it also aimed to test the validity of the two stereotypes of Tamil women which have emerged during the Sri Lankan conflict: one of the masculinized ‘woman warrior’, and the other of the ‘helpless victim’ of war and displacement.

Through this research, these images are both ultimately revealed to be overly simplistic portrayals: As Giles states, “women are seldom victimized or empowered by war: their experiences are more complicated”[6]. Likewise, rather than placing the entire burden of blame on the Sri Lankan state, patriarchal Tamil culture is also found to be culpable in explaining the current plight of FHHs in the north.

Findings: A diversity of response & resistance strategies

Succinctly put, the research found that FHHs have been uniquely, severely impacted[7] during the recent period of intensifying militarization, oppression of free speech and so-called ‘economic revival’ of the north (in which resources are devoted to mega-infrastructure projects, at the indirect cost of residents’ food security and housing needs). As lone wives and mothers, they are also more exposed to the increasing sexual violence in the north[8], face severe disadvantages in claiming and maintaining control over property[9], in securing the few jobs that are available and getting the same wages as their male counterparts due to systematic discrimination against female labor[10].

However, through a variety of strategies which are deployed in their everyday actions, these women endure, contest and resist both the older and more recent forms of domination imposed upon them. These strategies (discussed below) go beyond economic survival and also include emotional coping mechanisms and what could be considered as powerful ‘actions of everyday politics’.

Independent creation of livelihood opportunities

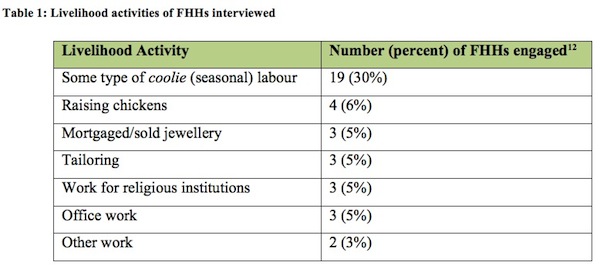

Perhaps the best illustration of FHHs’ agency in the north was their ability to create livelihood opportunities for themselves, usually through self-employment and other types of informal sector activities. Although rarely sufficient to meet their family’s basic needs, the majority (56%) of the FHHs interviewed had managed to find some way to earn income. A number of women also expressed a strong desire to access some credit in order to start their own businesses.

Even when women were unable to find regular sources of employment, they were able to survive financially through the distress sale or mortgaging of assets such as jewellery and household items[11]. Overall, they engaged in a range of ‘independent’ activities – i.e., those that did not involve some form of reliance on family or friends – to earn income for themselves and their dependents.

Interestingly, Amirthalingam & Lakshman found in their research on IDPs in eastern Sri Lanka that although men were more likely to earn higher incomes, they also tended to express more frustration over their inability to fulfill their financial responsibilites – clearly, a strongly gendered expectation[13]. Thus, FHHs’ ability to not only perform what they had been ‘gendered’ to do – i.e., household work and taking care of children – but to step out of the feminized sphere of the home and into the roles and expectations of men is remarkable.

Their abilities to earn livelihoods and at least partially meet their most basic needs is also especially impressive within an economy which is still recovering from almost 30 years of conflict. Although the government is rebuilding critical infrastructure such as major roads, railway lines, and the northern power grid, and the lifting of war-time restrictions on trade, land use and mobility has helped to boost certain sectors in the north (namely, agriculture, fishery and telecom), significant, urgent needs in the areas of food security, housing and protection, especially for recently returned IDPs, still remain unmet even while longer-term ‘reconstruction’ projects are undertaken[14]– a finding strongly confirmed by this research. Indeed, as other researchers have pointed out[15], the very term ‘reconstruction’ implies a return to the past and therefore a reinforcement of the power relations, inequalities and marginalisations that existed before a war or disaster.

The conditionalities of kin support

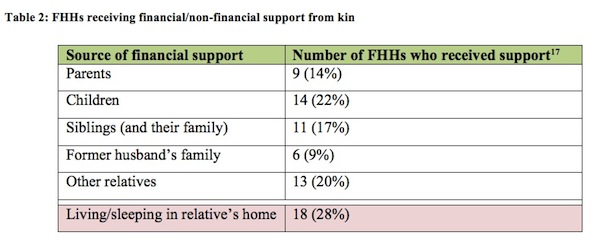

Although FHHs managed to create or find an array of livelihood activities on their own, family networks / kinship structures were also critical in providing both financial and non-financial support. As Ruwanpura & Humphries found in eastern Sri Lanka[16], the traditional networks of kinship reciprocity were being strained due to the additional number of widows created as a result of the conflict, which also left fewer traditional income earners (i.e., men) to provide economic support. Nevertheless, parents, grandparents, children, brothers, sisters, and more distant kin both within and outside of Sri Lanka acted as important sources of financial survival for 63% of the FHHs who participated in this research.

Kin were also important in allaying FHHs’ feelings of physical insecurity: with few exceptions, all of the women interviewed feared – to varying degrees – sexual violence, attack, kidnapping, and/or robbery, both against themselves and their children. FHHs perceived themselves as being physically vulnerable to a new spectrum of violence[18] in the postwar period as a result of: 1) living in the midst of a large, almost completely male, ‘foreign’ (Sinhalese) military, 2) introduction and now-widespread availability of pornography and alcohol – usually attributed to the military, 3) perceived corruption, complicity and ineffectiveness of institutions supposed to protect them against such abuses – e.g., the police, and 4) insecure housing.

It was revealed from the interviews that the most common coping strategy in the face of such physical insecurities appeared to be living and/or sleeping at relatives’ houses. Moving back to matriarchal homes was an especially common strategy. The emotional security and hope that family members provided through their sheer presence was also apparent from the interviews:

Friends, neighbours…are important, but in the end, it is the family who helps, who takes care of you. Others have their own problems, we are all in a bad situation, no? But at least my parents help, my children will be there to take care of me when I get older.[19]

Me and my children are living at the house of my sister and her husband. He has a good job, he works for the government. He is a good man […] It is difficult to be alone…difficult to manage…without my husband, but at least my sister is here, and my children are alive. That is why I continue.[20]

However, it should be noted that assistance from kin was rarely given unconditionally: FHHs reported needing to continuously demonstrate that they were conducting themselves ‘properly’ – especially with men whom they were not related to – and that their financial need was dire enough to necessitate kin giving money to them rather than devoting it to the needs of their own families. As Ruwanpura & Humphries state, “the quest to maintain respectability often involved not only sacrifices in terms of isolation and loneliness but also constraints on economic activities … [required for] the maintenance of that genteel status needed to secure kin solidarity and support”[21]. Thus, securing the assistance of kin required the ongoing reconstruction of their identities to correspond with the traditional image of the ‘good Tamil woman’ – that is, weak, meek, isolated and chaste.

It thus becomes clear from examining the conditionalities attached to support from kin that FHHs are severely constrained by ethnic and gendered narratives of ‘good womanhood’. Thus, although the Sri Lankan state has emerged as a key propagator of gendered oppression, ‘traditional’ Tamil culture is equally culpable in this respect.

Everyday practices of solidarity and resistance

Perhaps the most interesting finding of this research was the discovery that FHHs engage in what could be termed “acts of everyday politics”: traditionally thought of as being confined to the ‘formal’ realm of politicians and governments, Kerkvliet suggests an alternate conception of politics as everyday acts which affect the control, allocation, production, or use of resources. These can include tangible assets such as land or money, or intangible ones, such as education and social prestige. Thus,

everyday politics involves people embracing, complying with, adjusting, and contesting norms and rules regarding authority over, production of, or allocation of resources and doing so in quiet, mundane, and subtle expressions and acts that are rarely organised or direct. Key to everyday politics’ differences from official and advocacy politics is it involves little or no organisation, is usually low profile and private behaviour, and is done by people who probably do not regard their actions as political.”[22]

Thus, through such behaviours, individuals may consciously or unknowingly contest established orders of domination, and may do so not necessarily to show ideological dissent, but rather as practical responses to immediate concerns in their daily lives. Six types of response mechanisms which FHHs employed were particularly noteworthy as examples of “everyday politics”.

1. Information gathering and control

Participants in this research were generally very skilled at instrumentalising tools of information gathering and control. Anthropologists working a variety of settings have documented the use of such tools by local populations to identify, explore and tap into potential new opportunities to access aid. Several times during the course of this research project, news about a ‘foreigner’ being in the area spread extremely fast, even when attempts were made to limit such information from being widely known. FHHs often took the initiative of approaching me for assistance and presenting themselves in a light which highlighted and perhaps even exaggerated their vulnerability. Thus, they were consciously manipulating and contributing to the gendered discourses of ‘helpless victims’ that surrounded them, but in doing so, actually proving them false to a certain extent. Schrijvers, who had similar encounters with female Tamil IDPs during his research, posits that “powerlessness is not absolute; it can be manoeuvred as a resource, particularly when there is a fitting discourse such as that of ‘the vulnerable refugee woman’”[23].

FHHs were also adept in censoring each other to minimize the risk of ‘getting in trouble’ with the state. For example, a facilitator shared that earlier in the year, a journalist had come to one of the sites where fieldwork was carried out for this project to conduct some interviews. One of the FHHs had complained on-camera about how they were being neglected by the government and not receiving any assistance with the housing scheme. Her neighbours had later reprimanded her, fearing that that they would face punishment or some kind of retribution from the army, and as a result, she refused to answer any questions for this research project about her perceptions of the government. In another instance, a participant in one of the focus groups revealed at one point that she was a former LTTE cadre, immediately after which all of the other women admonished her for sharing such information with a ‘foreigner’:

Now they will come to all our homes, and we will all get in trouble! You should not keep saying things like this, be careful…[24]

Thus, FHHs vigorously engaged in everyday politics by gathering and controlling information in ways that maximized their access to resources, and minimized potential negative consequences from the state.

2. Silence

Closely related to the control of information and informal, quasi-clandestine gatherings is the maintenance of silence and a “low” profile by FHHs. As Blacklock & Crosby state, “in environments characterized by militarized and repressive social structures and relations, maintaining silence – that is, actively not contesting, disclosing, naming, or even remembering what one knows – as a strategy of survival and/or resistance ‘makes sense’”[25]. In this research, FHHs’ refusal to talk about certain issues – especially, their perceptions of the government and military – was likely just as revealing as the full disclosure of their feelings on these topics would have been:

No, no…talking about that is not necessary…I read the paper everyday…I know that talking about the government or army is dangerous.[26]

We cannot say anything, even if we trusted you. If they found out…[27]

Another topic on which FHHs commonly refused to speak was the loss of their husbands and other family members or loved ones. Their silence effectively spoke volumes about the depth of their suffering and the trauma that they continued to struggle with:

(Crying) I don’t want to think about that time again [when my husband died]. In those last days, we had to walk and swim over the dead bodies.[28]

(angry) Why are you asking about them? Why should I speak? […] Have I not suffered enough already? I just want to be left in peace![29]

FHHs’ refusal to speak on certain topics was thus a pragmatic response to the severe emotional and physical difficulties that they faced: by maintaining their silence, they avoided re-living horrific memories and subsequent re-traumatization, as well as becoming a potential target for the state.

Closely linked to maintaining silence on certain sensitive topics, participants attempted to evade ‘being seen’ by state authorities in two other main ways: reducing their movements outside the home, and avoiding contact with state institutions or people affiliated with them – even when doing so might have been beneficial for them.

I never wear my jewellery when I leave the house. Who knows what could happen these days?[30]

I could go outside if I really needed to, after 6 o’clock but I would not feel safe. Before, when the LTTE was here, I could do it…then, women could walk around freely. But now? No.[31]

It has been hypothesized that such evasive strategies in the face of repressive regimes are easier for women in patriarchal societies to adapt specifically because of the oppressive gender roles and expectations that they are habituated to. For example, in his research on Tamil female IDPs living in internal refugree camps, Schrijvers attributed women’s impressive coping capacities to having had low status and self-esteem throughout their lives. As one interviewee explained to him: “‘you know, we are women and therefore used to being nobody. This is why we can cope better with this than the men’”[32]. Men, on the other hand, were less adept at coping with their sudden change in status from being, for example, the economic provider to dependent on camp rations. Thus, while restricting their freedom to participate in certain opportunities outside the home, FHHs nonetheless appear to be able to instrumentalise the very power relations that subjugate women as a source of resilience and adaptability in the face of unexpected adversity.

3. ‘Rumor-mongering’

Tied to ideas of information control and silence were women’s abilities to portion out, manipulate and exaggerate the truth. These have been found to be a key survival strategy in contexts of ongoing repression. ‘Rumor-mongering’ could be considered one example of this type of behaviour. In particular, the real extent to which the largely Sinhalese military and Tamil men in these areas actually constitute a threat for women’s physical safety must be questioned, without being negated or unjustly diminished.

The propagation of such fears could be viewed as one means for the community to socially control the behaviour of Tamil women and men in an environment which was no longer regulated by the rigid rules of ‘proper conduct’ which existed during the periods of LTTE rule. As de Alwis has argued, the damage that conflict can render on the social fabrics of communities can led to heightened surveillance and scrutiny of women’s sexual conduct, as well as more severe social consequences for any behaviour viewed as ‘inappropriate’. Speaking about those displaced by conflict, she argues that the refugee woman is “frequently produced as a cipher for all that was (temporarily) lost as well as what must be preserved for the future; her community’s purity of displacement is imbricated in her moral purity”[33]. This representation of refugee women as both the symbols and markers of the community’s collective virtue is likely applicable also to lone FHHs since they too have been ‘displaced’ from the traditional roles of women within Tamil society. Seen as more vulnerable to ‘loose’ behaviour, they serve as ideal ‘litmus tests’ for gauging the moral uprightness of the larger community.

Furthermore, participants’ discourse about the military and Sinhalese men in general bore a striking resemblance to residents’ perceptions of Muslim refugee men in Puttalam in north-western Sri Lanka: “The residents’ predominant portrayal of the refugee men is epitomized by their ‘corrupting’ practices of watching blue movies, getting into fights, and drinking. The threat posed by these refugee men, however, is presented as the need to safeguard the resident women, who can ‘no longer walk outside [the household compound] after dark”[34]. Rather than being read as lies or pure exaggeration, it is more likely that such discourses are the manifestation of residents viewing the influx of military and the absence of the LTTE’s strict regulations as transforming their formerly ‘safe’ communities into constructed sites of impurity and disorder – just as de Alwais suggested that Puttalam residents did.

Another example of FHHs using ‘rumors’ to discourage interaction between other Tamil women and the Sinhalese military was illustrated during one focus group discussion: some (Sinhalese) soldiers stationed in the area had married local Tamil women. Participants in the discussion felt that these soldiers would almost certainly leave these women someday and return to start new families in the south. However, they could not recall any similar cases recently where soldiers had abandoned local women to re-marry in the south. Thus, even with the absence of the LTTE, the strict social control of women’s behaviour is attempted to be maintained by the community-at-large, including by FHHs themselves. This raises the widely acknowledge, important point that women in general are not only the ‘victims’ of patriarchy, but rather actively participate in its ongoing construction. It is only through greater awareness of the gendered norms that both men and women conform to and propagate that patriarchy can gradually be deconstructed.

4. Normalisation of horrific events

In addition to refusing to talk about certain topics, FHHs dealt with living in environments of fear and constant uncertainty by ‘normalizing’ such conditions as part of their daily lives. A 2009 study carried out in Jaffna found that the prevalence of common mental health problems experienced in conflict and post-conflict situations, such as PTSD, depression and anxiety, were actually less frequent than those found in similar studies carried out in Kosovo and Afghanistan[35]. The researchers hypothesized that given the protracted period of the conflict in Sri Lanka, affected populations had learned, over time, to better cope with ongoing exposure to conflict and to ‘normalize’ it in their thought processes as part of daily life. This is in line with Galapatti’s[36] argument that trauma in the Sri Lankan context is not necessarily outside the bounds of normalcy, given that the civil war which endured for three decades effectively dismantled traditional conceptions of what is ‘normal’.

(shortly after a tsunami warning had been issued for the area) Are you scared? We are so used to things like this…shelling, attacks, tsunamis. It is just normal for us.[37]

We are afraid of nothing now! After what we have survived, what we have seen…there is nothing they can do that could be worse than those months. The sounds of those bombs dropping from the sky, all day long, hiding again and again… leaving our parents, children and neighbours behind as they died…and we could not even bury them. All the fear is gone now.[38]

Tied to the normalisation of otherwise-unacceptable events and conditions was a strategy of maintaining low expectations that FHHs employed with respect to thinking about the future. Walker emphasises the performance of everyday, seemingly mundane activities as a critical way in which Tamil-speaking communities in Batticaloa in eastern Sri Lanka managed to endure the conflict, and remake their lives “in and around violence”[39]. Similarly, in this research, ‘mundane’ rituals such as cooking and cleaning, seemed to enable FHHs to focus on the struggles and joys that each day brought, rather than becoming over-whelmed by trepidation over what the future would bring (or rather, would not bring – such as their families, loved ones and livelihoods back):

I do not think about what will happen next…better to forget about the future and try to get through today.[40]

I keep busy with all my chores.. I do not think about the future. It just makes me afraid [when I think about the future]… I try to keep busy today.[41]

I do not think about the future. By the grace of God we have enough to eat, some clothes on our back. That’s enough.[42]

Such strategies act as powerful counter-arguments to the discursive constructions of FHHs as ‘helpless victims’ or ‘masculinized warriors’: it is as a result of their ‘victimisation’ that they find a sense of power in household tasks and the strength to endure ‘the everyday’. In these ways, they inhabit and thus transform the spaces between the two narrow identities offered to them.

5. Humour as a response mechanism

Another subset of FHHs’ normalization of both the terrible memories and current conditions which they suffer was embodied in the jokes that FHHs would make. For example, in one of the fieldwork villages, a young man had just been bitten by a dog and two of his neighbours – both FHHs – urged him to go to the doctor right away. He refused, saying it wasn’t anything serious: “it is not as if I am walking around without a head.” One of the women responded sarcastically, “who walks around without a head? Maybe only at Mathalan there are people like that.” All of them laughed at this comment[43].

At another fieldwork site during a group discussion with seven women, a tsunami warning had recently been issued. One of the participants joked that “at least if the tsunami comes, the government will give us something”, causing all to break out into laughter.

It seemed that humour was thus a key response strategy for some FHHs, enabling them to distance themselves from the horror which they had been through, as well as the multiple vulnerabilities that they continued to face. Simultaneously, mocking the people and the institutions (e.g., the army) that they perceived as being responsible for their suffering was also a way of contesting the unequal power structures in which they were embedded.

6. ‘Home’ as a source of strength

Membership in the larger communities (i.e., villages/towns/cities) which the FHHs saw themselves as belonging to[44] also constituted a crucial way for participants to both literally and figuratively make their way (back) towards ‘normality’. Most women expressed a great amount of satisfaction inhaving returned (or an intense longing to do so if resettlement had not yet taken place) to the sites of their traditional family homes, even if the physical structures of the homes were no longer standing.

If the war breaks out again, we won’t run away this time. God saved us last time so we could return to die on our own lands.[45]

Better to stay here and manage than to stay there [where we were forced to displace to] and suffer.[46]

Amirthalingam & Lakshman (2012) also found that IDPs in eastern Sri Lanka were deeply concerned about their inability to return to their villages. This was of more concern to women than men, and was not based solely on feelings of nostalgia – there were strong socio-economic motivations behind it as well. One of these was the livelihood activities which FHHs had performed that required access to the local natural resources which they could access at home. As a case in point, growing vegetables would be difficult to do in IDP camps or anywhere they lived where the land was not theirs to use as they wished.

Many types of non-financial support were also provided by neighbours and other community members in their original villages, based on generations of such mutual exchanges and solidarity.W hile money was rarely given outside of family networks, other community support mechanisms such as childcare, use of household assets (e.g., water well for those who did not have access to drinking water), and allowing single women and their children to sleep in their homes at night to minimize risk of attack were commonplace[47].

I do not have a well on my land, so I have to go to other people’s houses to ask to use their well…They are kind, the people here, they usually say yes […] I spend a while talking to them while getting the water, we also stay friends this way.[48]

Sometimes, the worry that my husband has died comes. But then, my friends […] come to my house and they make me feel so much better. They take me to their house, and they cook for me. They buy snacks for my children. They come over just to visit. They are like my family.[49]

Thus, the almost visceral contentment that FHHs found in returning ‘home’, or the intense longing to do so if resettlement had not yet occurred was a widespread response to the extended periods of displacement that most of the FHHs had experienced. It clearly gave them a greater sense of security, control and general well-being – for legitimate psychological and socio-economic reasons, as discussed above – than remaining where they had displaced to. This general rule seemed to apply almost regardless of the state of habitability of their family houses or hometowns.

Conclusion

Although the Sri Lankan state has emerged as a key apparatus of gendered oppression, the norms of ‘traditional’ Tamil culture are equally culpable. One obvious example of this is the societal censure brought to bear on FHHs who dared to step outside of the two constrictive identities offered to them by Tamil culture: the virtuous ‘warrior woman’ or the ‘powerless victim’ of war and displacement. Whereas appropriate moral and social conduct of women and men was dictated by the LTTE during the years of conflict, Tamil patriarchal ideologies and recent national state-led domination have now collided and fused, resulting in the imposition of new and varied forms of (attempted) control over, and marginalisation of, FHHs’ lives.

On the other hand, this research also confirmed the substantial resiliency of FHHs in the north through an impressive diversity of strategies. These ranged from creating their own livelihood opportunities to accessing kinship and other ‘alternative’ sources for both financial and non-financial support. A range of everyday politics that contested and resisted the asymmetrical power relations in which FHHs are embedded were also identified, as were several mechanisms that they used to ‘normalise’ the highly adverse circumstances of their daily lives.

As it thus becomes clear that groups such as FHHs in the north are neither ‘fine on their own’ nor ‘helpless victims’, it also becomes evident that donors, aid agencies and the international public must continue their engagement with Sri Lanka – in spite of the World Bank recently labeling it as a “middle income country at peace” – and focus on helping to create the environment necessary for affected populations to rebuild their lives.

This could be done in several ways: with Sri Lanka being heavily export-oriented, foreign countries have significant leverage which they could use to insist that the government prioritizes meeting urgent, basic needs in the areas that were most impacted by the war, over mega infrastructure or tourism development projects). The international community could also build on the momentum that it created earlier this year by passing a resolution at the Human Rights Council which urged Sri Lanka to implement the recommendations of its own lessons learned and reconciliation commission. In March 2013, progress on the implementation of these recommendations will be reviewed by the Council – and perhaps even a new precedent set by passing a second resolution with the same aim.

The current situation in Sri Lanka – and in particular, the needs of those perceived to be among the most vulnerable within its population – demands that the international community does not disengage its attention from the country. In spite of encouraging macro-level socio-economic statistics, “pockets of vulnerability” do indeed exist, with FHHs in the north being high among these. However, better understanding the coping strategies that this group is already employing in response to the multi-faceted challenges it faces should also offer donors a better idea of the kinds of support that are most needed.

[1]Group interview 1, Site 4, 04/04/12.

[2] Not the real name.

[3] See IRIN news (September 9, 2010). SRI LANKA: Women take over as breadwinners in north. Accessible at http://www.irinnews.org/Report/90429/SRI-LANKA-Women-take-over-as-breadwinners-in-north

[4] Although the definition of ‘female head of household’ is debated, for the purposes of this project, it was defined to include those women who bore the primary financial responsibility for themselves, or for themselves and other dependents. This usually encompassed family members who lived under a single roof, with some exceptions (e.g., when a child had migrated elsewhere but was sending remittances back home). In this research, the most common routes into female headship were widowhood, disappearance of husband or desertion/divorce, in that order.

[5]These discussions eventually formed the basis of a thesis dissertation for a Master’s in Development Studies.

[6] P. 1, Giles, W. (2003). ‘Feminist Exchanges and Comparative Perspectives across Conflict Zones’. In W. Giles, M. de Alwis, E. Klein, N. Silva, & M. Korac (Eds.), Feminists Under Fire: Exchanges Across War Zones (pp. 1-14). Toronto: Between the Lines.

[7] International Crisis Group (ICG). (2011). Sri Lanka: Women’s Insecurity in the North and East. Accessible at http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/asia/south-asia/sri-lanka/217%20Sri%20Lanka%20-%20Womens%20Insecurity%20in%20the%20North%20and%20East%20KO.pdf

[8] BBC. (2012, March 9). ‘Alarming rise’ of sexual abuse in Jaffna. Accessible at http://www.bbc.co.uk/sinhala/news/story/2012/03/120309_jaffna_child_abuse.shtml

[9] Fonseka, B., & Raheem, M. (2011). Land Issues in the Northern Province: Post-War Politics, Policy and Practices. Colombo: Centre for Policy Alternatives. Accessible at http://cpalanka.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Land-Issues-in-the-Northern-Province-Post-War-Politics-Policy-and-Practices-.pdf

[10] See IRIN news (September 9, 2010). SRI LANKA: Women take over as breadwinners in north. Accessible at http://www.irinnews.org/Report/90429/SRI-LANKA-Women-take-over-as-breadwinners-in-north

[11] This was the only time that debt was ever mentioned as a survival strategy, likely indicative of the fact that no other forms of credit, such as microfinance with a low amount of required collateral, were available to them.

[12] These numbers cannot be summed to arrive at the total number/percent of FHHs interviewed who engaged in some sort of “independent” livelihood activity as interviewees sometimes engaged in more than one. Therefore, these numbers are not cumulative.

[13] For a further discussion of the underlying factors motivating men and women’s differing reactions to economic and other vulnerabilities, see later section on “Normalisation of horrific events”.

[14] IRIN news. (6 July 2012). ‘SRI LANKA: Donor interest in north waning’. Retrieved July 12, 2012, from IRIN news: http://www.irinnews.org/Report/95814/SRI-LANKA-Donor-interest-in-north-waning

[15] Brun, C., & Lund, R. (2008, November). ‘Making a home during crisis: Post-tsunami recovery in a context of war, Sri Lanka’. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 29(3), 274–287.

[16] Ruwanpura, K. N., & Humphries, J. (2004). ‘Mundane heroines: Conflict, Ethnicity, Gender, and Female Headship in Eastern Sri Lanka’. Feminist Economics, 10(2), 173-205.

[17] These numbers cannot be summed to arrive at the total number/percent of FHHs interviewed who engaged in some sort of “independent” livelihood activity as interviewees sometimes engaged in more than one. Therefore, these numbers are not cumulative.

[18] The sources of these fears were not always clear, and it is likely that some of these sources of violence existed before the end of the war, especially domestic violence. Cockburn’s conception of a “gendered continuum of violence” which flows across periods of “war” and (relative) “peace” comes to mind here.

[19]Individual interview 4, Site 8, 12/04/2012.

[20] Individual interview 3, Site 10, 21/04/2012.

[21] P. 198, Ruwanpura, K. N., & Humphries, J. (2004). ‘Mundane heroines: Conflict, Ethnicity, Gender, and Female Headship in Eastern Sri Lanka’. Feminist Economics, 10(2), 173-205.

[22] P. 232, Kerkvliet, B. J. (2009). ‘Everyday politics in peasant societies (and ours)’. Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1), pp. 227-243.

[23] P. 235, Schrijvers, J. (1999). ‘Fighters, Victims and Survivors: Constructions of Ethnicity, Gender and Refugeeness among Tamils in Sri Lanka’. Journal of Refugee Studies, 12(3), 307-333.

[24] Group interview 1, Site 1, 31/03/2012.

[25] P. 68, Blacklock, C., & Crosby, A. (2004). ‘The Sounds of Silence: Feminist Research Across Time in Guatemala’. Sites of Violence: Gender and Conflict Zones, 45-73.

[26]Individual interview 3, Site 10, 21/04/2012.

[27] Group interview 1, Site 5, 10/04/2012.

[28] Individual interview 1, Site 8, 12/04/2012.

[29] Individual interview 3, Site 9, 20/04/2012.

[30]Individual interview 1, Site 10, 21/04/2012.

[31] Individual interview 1, Site 8, 12/04/2012.

[32] P. 323, Schrijvers, J. (1999). ‘Fighters, Victims and Survivors: Constructions of Ethnicity, Gender and Refugeeness among Tamils in Sri Lanka’. Journal of Refugee Studies, 12(3), 307-333.

[33] P. 227, de Alwis, M. (2004). ‘The “Purity” of Displacement and the Reterritorialization of Longing: Muslim IDPs in Northwestern Sri Lanka’. In W. Giles, & J. Hyndman (Eds.), Sites of violence: gender and conflict zones (pp. 213-231). Los Angeles: University of California Press.

[34] P. 227, ibid.

[35] Husain, F., Anderson, M., Cardozo, B. L., Becknell, K., Blanton, C., Araki, D., et al. (2011, August 3). Prevalence of War-Related Mental Health Conditions and Association With Displacement Status in Postwar Jaffna District, Sri Lanka. Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(5), pp. 522-531.

[36] Galapatti, A. (2003). ‘Psychological Suffering, “Trauma,” and Ptsd: Implications for Women in Sri Lanka’s Conflict Zones’. In W. Giles, M. de Alwis, E. Klein, N. Silva, & M. Korac (Eds.), Feminists Under Fire: Exchanges Across War Zones (pp. 115-130). Toronto: Between the Lines.

[37] Translator, Site 6, 11/04/2012.

[38] Group interview 1, Site 1, 31/03/2012.

[39] P. 15, Walker, R. (2010, March). ‘Violence, the everyday and the question of the ordinary. Contemporary South Asia’, 18(1), pp. 9–24.

[40] Individual interview 5, Site 9, 20/04/2012.

[41] Individual interview 3, Site 10, 21/04/2012.

[42] Individual interview 2, Site 8, 12/04/2012.

[43]Puthumathalan, also referred to as Mathalan, on the northeastern coast of Sri Lanka, was one of the designated ‘no-fire zones’ towards the end of the conflict, where shelling by government forces is nevertheless reported to have repeatedly occurred and caused some of the most heavy civilian casualty numbers of the last phase of the war (see ‘Report of the UN Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka’ (2011)).

[44] Different women perceived “home” in different ways: usually, it was either their place of birth and upbringing, or the place they had been living in before being displaced during the last phase of the war.

[45] Group interview 1, Site 5, 09/04/2012.

[46] Group interview 1, Site 7, 11/04/2012.

[47] This does not necessarily imply that solidarity was always strong within villages or communities, or amongst FHHs. For example, in one of the fieldwork sites (Site 5, 09/04/2012), participants complained of the existence of army informants within the community and of selfishness among village members in trying to monopolize the aid that was offered by NGOs.

[48] Individual interview 2, Site 5, 09/04/2012.

[49] Individual interview 4, Site 8, 12/04/2012.