In less than two weeks since the Darusman Report (hereinafter referred to as the Report) was handed over to the United Nations Secretary General (hereinafter referred to as UNSG), a large number of articles have been written about the report, its motivations and on its impact on Sri Lanka. Except in several exceptions, the majority of these renderings seem to have lost the plot, in their failure to provide adequate attention to several key issues surrounding the report, or the ‘leaked’ version of it published in the Sri Lankan newspaper The Island. Public reactions to the leaked sections of the Report are best glimpsed from Groundviews, where comments made by readers include rather heated debates on issues such as the number of Eelam War IV casualties raised in the Report.

One such key factor is that the Report is critical of both adversaries of Eelam War IV, the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Reactions to the Report from Colombo accuses the UN over undue interference, and rejects the accusations laid against GoSL and the state military forces. The Tamil National Alliance (TNA), a political alliance that, during a substantial period of time, represented the Tamil cause in the Sri Lankan parliament, with a political discourse built on Tamil nationalism, oftentimes in relative alignment with the LTTE’s secessionist discourse of Tamil nationalism) fails to ponder on the accusations levelled against the LTTE in its communiqué on the Report.

Media reports show that Colombo is preparing for a campaign to raise a strong public opinion (read ‘Sinhalese’ public opinion) critical of the Report. Key arguments put forward to defend this position would be that the Report, the UN and UNSG are all elements of an international conspiracy against GoSL and Sri Lankans, and the Report is a vicious document intended at tarnishing the ‘image’ of the state military forces. Among the dominant arguments is the fact that the security situation in the ‘Sinhalese south’ has considerably improved since May 2009, with the virtual absence of a fear psychosis, devoid of suicide bomb attacks and frequent checkpoints. A quick look at comments made by readers on many a news website may suffice to notice that this view is strongly espoused by a significant segment of the Sinhalese community. Moreover, there can indeed be members of the Tamil and Moor communities who also subscribe to this viewpoint. In any case, it is clear that the Rajapakse administration will not face major problems in mounting a strong public outcry in Sri Lanka against the Report.

Some analysts have indeed touched upon the issues of credibility and transparency in terms of the international community. The West, and the UN for that matter, where Western power bases operate in a dominant position, with the veto of Russia and China in the Security Council being the most notable exceptions, tends to have an international agenda that responds primarily to Western interests. The best of current examples in this respect would be the Western intervention in Libya, as opposed to its tongue-tied and blindfolded attitude towards the extremely violent repression of popular protests in Bahrain, ruled by a trusted ally of the West, who, it is reported, will grace the British royal wedding coming Friday. One can also notice a Western media blackout on Bahrain, with only media houses such as Iranian Press TV broadcasting news regularly on the carnage in that country.

In terms of Sri Lanka, the Rajapakse regime has been at odds with the West for a good while. Relations with Washington DC have been ailing, while Assistant Secretary Robert Blake’s meeting with representatives of the Global Tamil Forum (GTF) seems to have added hay into the fire. Relations with the European Union (EU) have been slack since the days of Eelam War IV, with the rejection of a diplomatic visa to Swedish Foreign Minister Karl Bildt (during the Swedish presidency of the EU), and Colombo’s stern resolve to go ahead with its own agenda despite the Miliband-Kouchner combined effort to make Colombo change its strategy. The GSP Plus exportation benefit was brought up as a shield, which once again did not bring expected results. The infamous ‘Oxford debacle’ was yet another incident which, despite being a mere invitation from the Oxford Union – a student association at Oxford University and not an event that concerns UK-Lanka diplomatic ties, hinted at the ‘unwelcome’ reception of Colombo in the West. The ‘state’ of the Rajapakse regime’s relations with the wider ‘West’ can be glimpsed by comparing it with that of the Kumaratunga administration. Those were years when the President of Sri Lanka was a frequent and welcome guest at Palais d’Elysée and Hôtel Matignon (and in other Western first residences) regularly met with senior officials of governments and opposition groups, and maintained close links with the EU’s foreign policy bodies and international organisations such as the Commonwealth of Nations, where the UK occupies a historically significant position. The situation was quasi identical in the Ranil Wickramasinghe government (2001-2004), when the Prime Minister of Sri Lanka was warmly received at the White House, No 10 Downing Street, in Brussels and elsewhere in the West.

The clock has turned a full circle, with the West’s Sri Lankan allies of yesteryear in the opposition, and the Rajapakse regime colliding with the West. This situation can be explained as an ultimate consequence of a transformation of Sri Lanka’s internal politics vis-à-vis the ethnic conflict since 1994. While a strong public opinion in favour of a negotiated settlement dominated when President Kumaratunga was elected that year, it gradually diminished with the failure of the peace process of 1995. The situation further deteriorated with the failure of the Norwegian-facilitated peace process (2001-2006), when the government was accused of infringing territorial integrity, Norwegian facilitation was negatively perceived, and violence escalated, providing Sinhala nationalists fertile grounds to sow the seeds of a pronouncedly Sinhala nationalist political discourse – one that clearly maintained that only an exclusively military strategy could effectively address the ethnic conflict. In the persona of President Rajapakse, such forces found the ideal Sinhala Buddhist (and Sinhala nationalist) leadership to execute this agenda. The ultimate consequence has been paradoxical: strong and unprecedented power of President Rajapakse within Sri Lanka, and the Rajapakse administration’s international relations, especially with the West, not in the best of shapes – to say the least. The new order has had a profound impact on foreign policy, with the development of new strategic partnerships with southern states and emerging power-blocks. The conflicting relations with the West stand in contrast with friendlier ties with Libya, Iran, Myanmar, China and Russia, among others.

It is in such a situation, with Sri Lanka’s international relations at crossroads, that the Report has been handed over to UNSG. Latest news reports state that despite Colombo’s requests, the UN is planning to publish the full report. As legal luminary G.L. Peiris contends, the panel that investigated the issue of war crimes and drafted the Report was an ‘advisory’ panel appointed by Mr Ban-Ki Moon in his capacity as UNSG, and therefore does not equal an investigative body sanctioned by international law. Legally speaking, the Report per se could do little to press legal charges on the Rajapakse administration on war crimes.

Reconciling domestic pressures – when domestic groups pursue their interests by pressurising the government – and foreign policy concerns is a fundamental challenge that central policymakers cannot avoid. The Rajapakse administration’s dilemma with regards to the Report and the wider realm of foreign policy largely lies in its efforts to manage ‘the local’ and ‘the international’. The dominant political discourse that brought it to power, facilitated its major policy decisions and ensures its continuity, and those espousing that discourse need to be favourably dealt with on the home front. In terms of foreign policy and international relations, the administration faces new challenges in the backdrop post-May 2009 developments. Herein lies the rather tough task of managing domestic and foreign concerns. A news website with a dissenting voice reported a few days ago that President Rajapakse had expressed his dissatisfaction to the Attorney General and the Minister of Foreign Affairs over the failure of their mission to reach a working compromise with Mr Moon. The same news item also quoted the President noting that it is at such circumstances that the absence of the late Lakshman Kadirgamar is deeply felt (i.e. in this case, the Report issue). While the veracity of this news item remains questionable, the very fact that there remains space for it to be in the news points at a problematic situation in terms of foreign affairs and foreign policy management. While the ministerial portfolio in question is in the hands of an outstanding scholar and experienced politician, the problem seems to stem from a wider complication, related to the overall policy orientation of the Rajapakse administration, and to its strategies of effectively managing domestic concerns and what Robert Putman describes as adverse consequences of foreign developments.

One columnist notes that the Rajapakse administration will develop the ‘anti-UN’ discourse to keep the general public occupied, as prices of essential goods are on the rise. The point would be to stress and re-stress the fact that the ‘freedom’ prevalent in present-day Sri Lanka is a hard-earned one, that the people should be grateful to President Rajapakse, and that he (and his government) should be protected in the name of freedom and peace. This may certainly be the objective of the Rajapakse administration on the home front. As the Report stems from the realm of Sri Lanka’s international relations, what is the Rajapakse administration’s strategy on the international front?

One of the most advisable suggestions that this writer has come across so far is from a citizens’ group called the Friday Forum. In a communiqué drafted on behalf of the Friday Forum by distinguished retired diplomat, it is noted that Colombo ought to exercise minimum restraint, effective diplomacy and dialogue in responding to the Report and to UNSG.

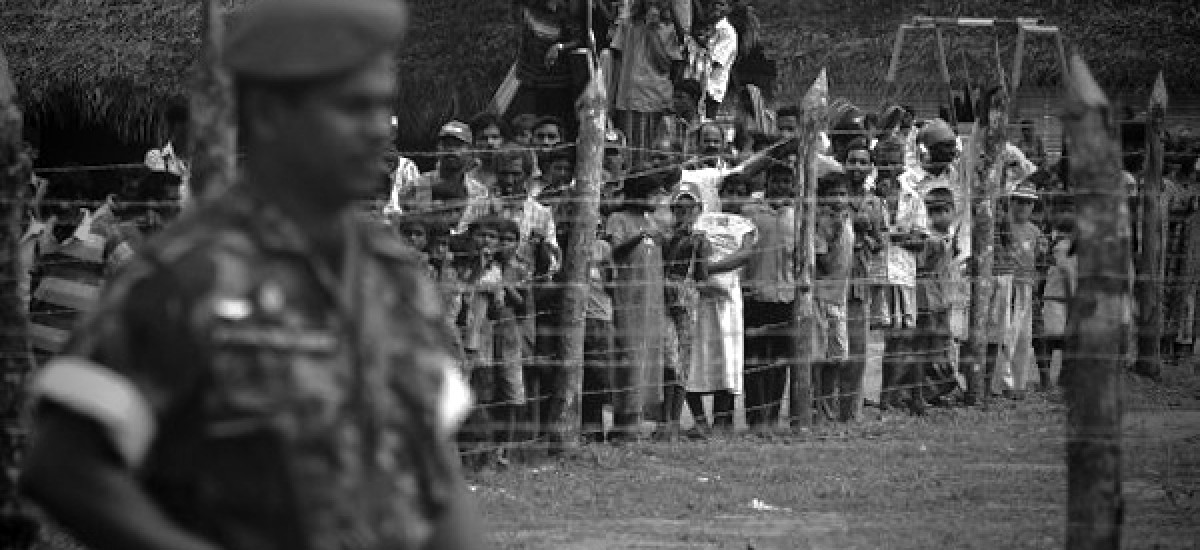

The focal point raised by the Report is that of reconciliation, coupled by a repeated highlighting of the challenge of reaping the best dividends of peace. In order to reach this objective, a sustained strategy is required, and such a strategy essentially calls for a consistent national policy on reconciliation. Such a policy should be sufficiently multi-faceted to encompass the complexity of the issue – ranging from public security in the Northern and Eastern Provinces to the management of hardline nationalism/s and engaging with diaspora communities. A reconciliation policy cannot take off in the absence of sufficient engagement by the highest authorities concerned over public security situation in the North and East (especially the North – which has lately witnessed an upsurge of crime including murder and assault). Despite political positions and affiliations, citizens of all ethnic and religious groups should be enabled to feel and live the sense of ‘freedom’ and ‘peace’ felt by Sinhalese people in the Sinhalese south, as referred to earlier in this article.

A starting point of this nature would enable Colombo to keep on the right track, and maintain a level of balance in terms domestic and foreign policy – and avoid questionable gaps. Intense military activity inevitably results in casualties, and it is not detrimental to the state or to the security apparatus to carry out transparent and impartial investigations into questionable policy decisions and acts during Eelam War IV and include the results of such processes in the public record. It is also of primal importance to develop a strong public opinion in favour of a collective reconciliation process, similar to the movement that facilitated the collective public endorsement of Eelam War IV within Sri Lanka. Reconciliation is a quintessentially two-way process, and despite Colombo’s victor-psychosis, it is not well disposed to carry out a one-way reconciliation drive, exclusively on its own terms. Inconsistent measures of that nature will result in the West seeking possibilities of exercising leverage on the Rajapakse administration, which they perceive, as leaked Wikileaks amply show, a rather boisterous and uncontrollable entity.

In the final reading, this writer maintains that Colombo has every right to question the Report and its underlying motives, thereby questioning a broad range of hypocrisy that characterises the international system. Nevertheless, such questioning needs to take place in the backdrop of a consistent post-war reconciliation policy, that constructively brings the pieces of the messed up puzzle together, thereby ensuring that next to no cracks are left for any external force to infringe what could be deemed ‘Sri Lankan interests’ by all Sri Lankans, irrespective of ethnicity, religion or divisions of any other sort.