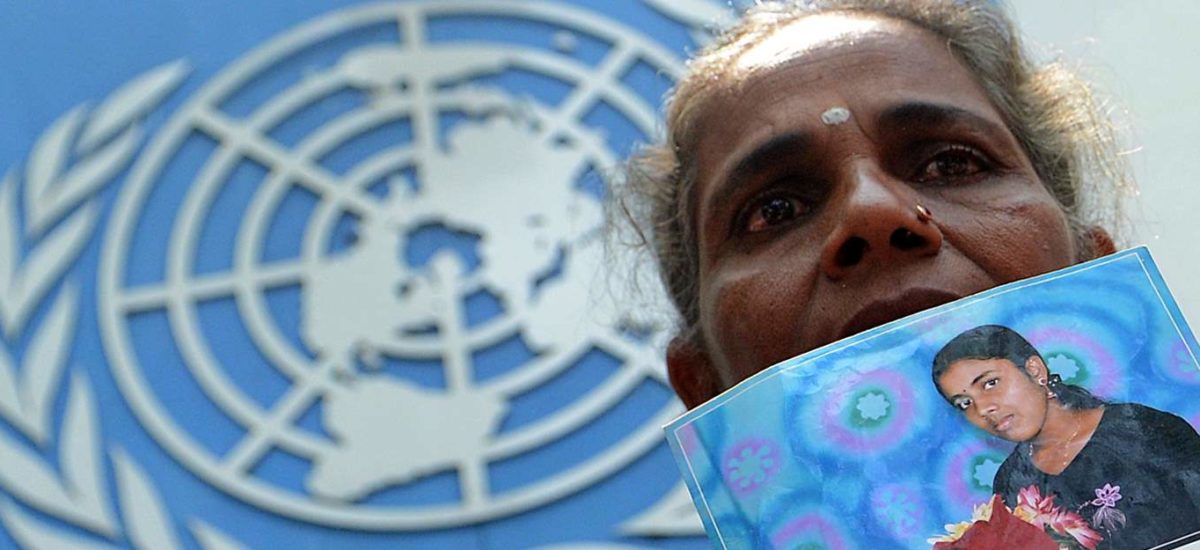

Photo courtesy of Amnesty International

The Sri Lankan government, faced with grave international concerns about human rights, has made little effort to soften its confrontational approach at home or abroad. As a result, it faces a highly critical resolution at the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) which, despite its efforts, may well be passed.

The effects of this hardline stance will shortly be clearer. Any defeat for the Rajapaksa government may well be shrugged off, indeed boasted about to gain popularity with the majority community. A victory, however narrow, would lead to deeper despondency among survivors of historical and recent abuses and, almost certainly, further violations.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and those he favours may claim his position is about protecting national sovereignty. But history has shown that this is weakened and all communities harmed when human rights are disregarded (and the government’s attempts to pander to the Chinese and Indian regimes hardly signal independence). And the agreement of the resolution would be a major diplomatic defeat at a time when international cooperation is vital in dealing with the effects of the pandemic, as well as having been entirely avoidable.

No major compromise, though maybe minor concessions

A report in January by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights underlined the regime’s refusal to address war crimes committed by both the armed forces and Tigers during the civil war and worsening situation for human rights and democracy. A Core Group of other states had approached the Sri Lankan government to try to draw up a consensus resolution in an attempt to find a way forward but had been rebuffed. This tack of worsening repression in the country and defiance abroad continued, along with attempts to persuade powerful allies to use their influence on the regime’s behalf to protect it from being held accountable for its treatment of those in its power.

By early March, although the Core Group had kept trying, the government refused to make any major concessions on improving the lot of ordinary Sri Lankans; however the cruel ban on letting Muslim families bury COVID-19 victims was removed. The Indian government, perhaps predictably, has shown reluctance to throw its whole weight behind that of Sri Lanka, given the risk of offending many of its own citizens, while the Chinese leadership is supportive of the Rajapaksa regime. One newspaper account claimed that, in negotiations, Sri Lanka’s ambassador to the UN went out of his way to antagonise officials and representatives of other countries. If true, this might indicate a government preference for confrontation rather than consensus.

The wording of the resolution became slightly stronger but some human rights campaigners and diaspora groups felt it was still too weak.

A high risk strategy

There is a strong possibility that later in March, the HRC will pass a resolution highly critical of the Sri Lankan government. Myths and misinformation about the process are widespread in Sri Lanka and the leadership may be able to persuade many of its citizens that the criticisms are unfair. Yet, if more Sinhalese Buddhists who are not rich or well-connected lose faith in the Rajapaksas over the next few months, this could be a risky strategy. So far, human rights campaigners have often failed to make connections among the many ways in which erosion of social, economic, political and cultural rights are affecting diverse people. If those links are more widely understood, the grip of the current leadership may be loosened, however violent its defence of its own power.

Alienating other governments and large sections of the public internationally may prove awkward for the government amidst economic and social pressures, while the price for support by China and other allies may be high. A more conciliatory approach, as well as easing the suffering of those bereaved, displaced or intimidated, might have healed divisions as well as gaining a broader support base worldwide.