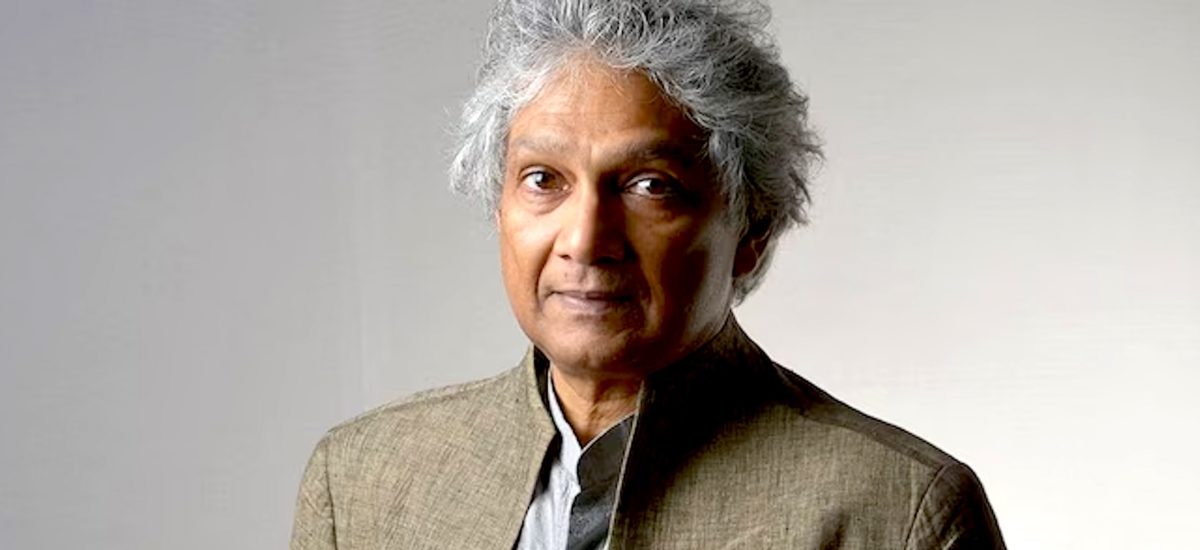

Photo courtesy of Reader’s Digest

Sri Lanka authors have been in the limelight recently, hitting a peak with Shehan Karunatilaka’s 2022 Booker Prize for The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida. Kanya D’Almeida won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize two years ago and this year New Zealand based Himali McInnes has been shortlisted for the same prize.

But it has been a well-trodden path with Michael Ondaatje winning the Booker Prize in 1992 for The English Patient and Romesh Gunesekera shortlisted for the same prize in 1994 for Reef. Other award winning Sri Lankan writers include Shyam Selvadurai and Anuk Arudpragasam whose novel, A Passage North, was shortlisted for the 2021 Booker Prize.

Many of these authors have one thing in common – they live in another country but write mostly about their birthplace. But do they create, as Salman Rushdie said, an imaginary homeland based on stereotypes coming from a colonial past, stuck in an unrealistic time warp?

Rushdie’s collection of essays, Imaginary Homelands, describes the dilemma of diaspora writers as they attempt to reconnect with their birthplaces. However, the reconnection often fails due to incomplete memory. They are out of touch with their homelands and this alienation is a theme running through much of their work.

Rushdie believes that the migrant, whether from one country to another or from one language or culture to another, “is, perhaps, the central or defining figure of the twentieth century.”

Born in 1954, Romesh Gunesekera is a double migrant, leaving Sri Lanka in 1967 to join his father who was one of the founding members of the Asian Development Bank in Manila and then in 1971 going to study in England, where he has been living ever since.

For 15 years, he wrote unsuccessfully until gaining recognition for his collection of short stories Monkfish Moon in 1992 and his first novel Reef in 1994. At that time, there was very little writing in English about Sri Lanka and what people knew of the country was based on the violent civil war. One reviewer said Monkfish Moon was “a vivid portrait of a largely unchronicled corner of the world.”

Groundviews spoke to Romesh, who is in Colombo as Chair of the Jury for the 30th Gratiaen Prize, on how he depicts his homeland, his hopes for Sri Lanka’s future and wanting to be a pilot.

The themes of migration, exile and identity come up frequently in your work. Do you feel displaced?

I don’t feel displaced, not in the way some people do or others think I do. I was lucky as a child to have travelled a lot. I actually felt displaced growing up in Colombo in the 1950s and 1960s because of the kind of kid I was. I used to read a lot so I was living in another place, not here. In my head now, I am often back here. Home not a place, it’s in my head. London where I live and Colombo are not so separate but just one big place at other ends of the world. Coming to Colombo doesn’t feel that different. In fact when I was leaving this time, the temperature was the same and there were thunderstorms in both countries. But of course the challenges are different.

Other than entertainment, what impact do you want your writing to have on your readers?

I don’t think of my writing in those terms but I do want my writing to entertain. Good writing should both delight and inform, as they say. Imaginative writing should give people a sense of self and sensitise them to the world we are all living because it is the same world.

Do you have any misgivings when writing about Sri Lanka’s violent past? Do you sometimes self-censor?

No I don’t self-censor but I am a careful writer and think a lot about the words I use so as not be unfair or use stereotypes. It is a matter of how you confront violence and what you do with it. Memories are very short and in Sri Lanka, even shorter. Politics shows us how short memories are and how little we learn. I have chosen to write books where the characters are as real as possible so you feel that they are real people you have met. I look through the eyes of the characters and give them a voice.

You wrote a moving poem about the aragalaya which ended on a note of hope. One year later, are you still hopeful for meaningful change?

You can’t live if you lose hope. I have lived long enough to have seen big, big changes all over the world. Hope doesn’t go away but there are always new challenges. We have big challenges coming and it is not going to be easy. When there are immediate challenges, it is humanly difficult to think of other people’s challenges and bigger challenges.

Do you write keeping in mind that you are addressing non Sri Lankans?

It depends on the setting and the novel. It’s been almost 30 years since Reef where I used words such as kolla. It has now come to pass that Sri Lankan writers can write in a language we recognise and everyone can understand. It has happened through food and cricket. You can buy kottu rotti in London; people have learnt to pronounce cricketers’ names. Gunesekera is a difficult name and ironically misspelt more here than abroad.

Why has it taken some time for Sri Lankan authors to get recognition?

It is now looking good for Sri Lankan writers in English but it has been tough. When Monkfish Moon came out in 1992, people were not interested; even here newspapers had a small article about this person who had written a book. Now we are known outside and inside Sri Lanka. India is different because of its size. In the 1990s, when Indian writing was being acknowledged, there was a photograph of several authors in the New Yorker, where I was also included as coming from Sri Lanka in brackets. It is a slow process.

The early years before you became established must have been difficult. Did you ever think of giving up?

I teach writing at workshops. I don’t like to discourage people by saying how difficult it was for me. I wrote for 15 years writing without being published. Suddenly one day in the 1980s for the first time I wrote a story with Sri Lankan characters, and they were real people. It made me realise that this was where my imagination worked best. It was me trying to understand the Sri Lanka I belong to and belongs to me and that can belong to anyone else. The writing brought me closer home and taught me something about me. Writing used to be a one way conversation but now with social media there is more interaction with readers. But what matters is not the talk but that someone reads your books and feels something about them.

Did you have a particular moment when you knew you wanted to be a writer?

Living in Sri Lanka made me a reader because I wanted to get away from everything. Living in the Philippines made me want to be a writer, which came from reading books. These books were written by people who were interested in being writers; people who did this as a thing they wanted to do. Once I was in England, I read more widely.

Do you have a favourite book of yours?

I don’t have a favourite but the early books such as Monkfish Moon and Reef were important. The day it was printed I was on stage with Salman Rushdie. The book was brought into the auditorium and he said it looked nice but that it was very small. Reef brought me a readership. At that time there were few Asian writers and very few books that got noticed. It was the book that made a difference.

What’s the most enjoyable part of the writing process?

The early part of writing is a joy for me and it’s what I protect the most. Writing is the best thing in the world but don’t do it unless you enjoy it.

What are you working on now?

I am working on several writing projects – a novel, short stories, poem and a play. I live in my world. I am writing because I like to write. That’s all.

If you hadn’t been a writer what would you have been?

When I was a kid I wanted to be like Elvis or the Beatles but I knew it was unrealistic so I decided I wanted to be a pilot. I wanted to go to the airport to see the planes taking off and my mother asked why since I had been on planes and I said when I was inside the plane, I couldn’t see it taking off. Once I went to a pilot’s house and he had chocolates and ice cream he had brought back at a time when you couldn’t get anything in Colombo. Unfortunately in those days you needed 20/20 vision to a pilot and I needed glasses to see.

What sort of a writer do you want to be remembered as?

A good writer.

Read Romesh’s poem on the aragalaya here – https://groundviews.org/2022/05/02/galle-face-green-2022/