News broke on the morning hours of October 18 that Shehan Karunatilaka had become the first Sri Lankan author since Michael Ondaatje to win the Booker prize. The following hours, days and weeks saw Sri Lankans bask in the glory and recognition this had brought the country. Amidst a tired and difficult year, this was something to be happy about; a Sri Lankan making the news for the right reasons.

Along with the novel’s increasing appeal and recognition came a process of meditation on the past (if you will). A process of revisiting tragic and dark times marked by senseless atrocity and indiscriminate violence but also of re-learning through retrospection marked with cautious hope and fond remembrance. Sharika Thiranagama tweeted her appreciation for Karunatilaka for the way he had captured the subtleties of her mother as she read through the book on the anniversary of her mother’s murder. Elsewhere, readers began to note how the novel’s protagonist closely mirrored the life of Richard De Zoysa. Kris Thomas of RoarLK tweeted on the novel’s brief mention of the Southern Mothers’ Front that formed after the second JVP Insurrection. In a follow up tweet, Thomas quoted Namal Rajapaksa’s congratulatory tweet for Karunatilaka: “Guess who founded the front? Two SLFP MPs, Mangala Samaraweera and Mahinda Rajapaksa. One of whom was later accused of disappearing more sons, husbands and brothers when he became President.” Not to be outdone in the irony however, President Ranil Wickremesinghe, who was part of the then UNP government that allegedly murdered De Zoysa, followed suit and also tweeted his congratulations.

It goes without saying that the praise for the book is warranted. The way in which Karunatilaka guides his reader through a sensitive topic with wit and due respect is worth the adulation; the Booker prize win a testament to that. And yet, one can’t help but note the great deal of irony in how The Seven Moons of Mali Almeida has been received in Sri Lanka. A book that details how an era of mass killings and the pattern of impunity that followed defined our island during the late 20th century; these which have neither been addressed, widely recognised or taught, let alone impartially investigated to provide relief to victims. The Education Ministry’s priority as of now seems to be teaching Artificial Intelligence to O/L students while Sri Lanka’s history curriculum still continues to harp on the achievements of Dutugemunu and D.S. Senanayake, without reflecting on the more pressing periods of our history that define the Lanka we live in. Within such a climate Karunatilaka’s novel is a source of recognition and praise; although apparently not for its tackling of these topics but for its contribution to placing Sri Lankan literature on the global stage. All this well wishing was topped off by the congratulations Karunatilaka received from Sri Lanka Tourism. For writing a book highlighting the systems of injustice and impunity within our country, the author was bestowed with a tweet of an image of himself and his prize with #VisitSriLanka #SoSriLanka proudly stamped underneath.

On the same week of Karunatilaka’s win at London, in Colombo the loved ones of those who disappeared during the 87-89 JVP insurrection gathered for a media introduction of sorts. It was a rare moment where these families in the south had come together to appeal their cases directly to the media; a media that has often failed to hold account of the atrocities that have black marked Sri Lanka. At the meeting were 15 victims of the beeshanaya era. Some were mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers of those who had been abducted and disappeared. Three others were those who were lucky enough to escape the torture houses and prison cells that had earmarked them for a violent death 30 years ago.

Britto Fernando, chair of the Families of the Disappeared in his opening remarks states that the families want to communicate to the public that the atrocities that have defined their lives occurred regularly in the past, and have the ability to happen again if not discussed and taught. Part of this process involves the families revisiting their lowest moments again and again so that these stories will, if nothing, inform future generations of what has occurred in the past. Many of those present had given up hope on securing any form of justice for what they have endured, and so it is their stories and the power that they bear that carry some sort of currency.

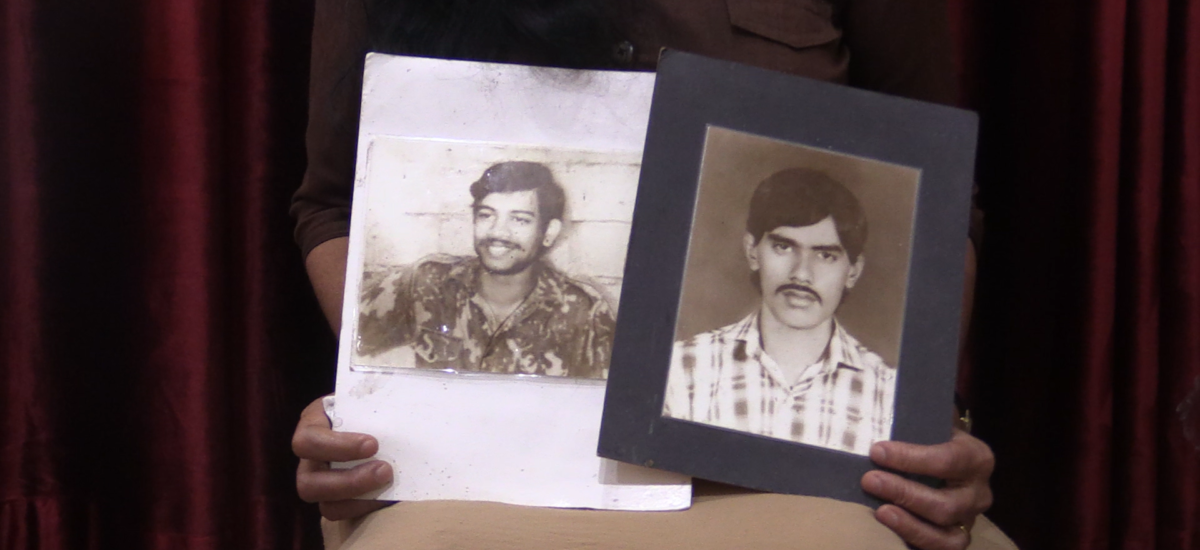

Jayanthi Amarasinghe, whose son and husband were taken away from their home in Mirihana had some hope when President Mahinda Rajapaksa was elected president for the first time in 2005. She had personally spoken to him and told him how the Mirihana police had even refused to take down an entry of what she had seen and heard. “He took the photographs of my son and my husband, too.” She held out hope. Rajapaksa’s work with the Mothers’ Front and his reputation as a human rights defender was something she could place her trust on.

“But to date, nothing has happened. Whenever a politician thinks of coming to visit me, I chase them away. What is the point?” she asks.

As Mahinda Rajapaksa was working with the Mothers’ Front to help mothers pursue justice for their missing loved ones, his brother Gotabaya was behind a spate of disappearances in the Matale District. Britto Fernando relates a story of how a former soldier whose brother had been abducted and held by the army approached the then Lieutenant Colonel Rajapaksa when he was serving as the District Military Coordinating Officer and asked for his brother’s safe return. What the soldier got in return was the threat of a similar fate to that of his brother.

Chandrika Kumaratunga had campaigned with the Mothers’ Front in her first appearance as a presidential candidate, as a widow aligning herself with the pain of many of those in the front. Her victory brought about some hope that justice might be within reach. Her government created three regional Presidential Commissions of Inquiry into involuntary removals and disappearances. These went on to find a number of security personnel behind the abductions and made recommendations that if pursued could have revealed the truth and ensured justice, reparation and non-recurrence but, needless to say, none of these were delivered. Security officials implicated in these crimes continued to be in active service and, in a cruel twist of fate, with the restart of hostilities with the LTTE in 1995 saw promotions come their way.

The politics and the people

Justice for the disappeared has been a point in an election manifesto rather than an actual moral responsibility. Stories that make good on first time election campaigns promising the reform of a corrupt political culture lose their purpose after victory. Almost all those who had gathered at the meeting could attest to this; especially Sinhalese mothers, who have been platformed for sympathy on the basis of the language that they communicate their loss in. There are no such concerns for the disappeared families in the North. And so when revisiting these stories, patience sometimes wears thin. There is exasperation, sometimes suspicion, but always pain. Pain in the knowledge that answers are elusive and time unforgiving. Pain in the knowledge of the silence that follows no matter how many tears are shed. There is still difficulty in holding on to a past that is marred by violence and leaving that behind for what the present holds. Deewasi Kotikawatta lives with her son who has forbidden her from speaking of what happened to her brothers in the late 1980s. “I came here without his knowledge,” she says, after relating her story.

“If he found out he would be quite upset. Most young people don’t know what happened then. Others have no interest in finding out. I can’t forget what happened, even though I have a life ahead of me with my son and his family,” she says.

This isn’t a luxury offered to all, however. For those like Jayanthi Amarasinghe, who lost both her son and husband and was continuously harassed by the police after that fateful day, the idea of letting go of the past is not an option. The pain is in the present, readministered each day. When she relates her story it cuts through time. It isn’t placed within that December night in 1989 or the beeshanaya era or any other defined period of time. Memories don’t seem to be triggered by the mention of a place, person or time. It’s present in the here and now as it was thirty years ago. She has no hope of finding out the truth of what happened to her husband and her son but she will live with it.

It’s a similar case for Karuna Ekanayake. Her two sons, Nishantha and Samantha, were abducted while she was working abroad. Her only connection to those last moments her children were safe is somewhere in the frail mind of her husband, Sirisena, who lost his senses after he was assaulted and beaten while trying to stand in the way of his sons’ abductors. She came home to a broken and empty home, a disoriented husband and two missing children. There is uncertainty and confusion in every second. As Karuna convey’s her story, Sirisena interrupts, “Where are we? When are we going home?”

“If at least I knew what happened to them, we could have something to remember them by. We could have at least organised an almsgiving in their name,” she says.

Three stories among fifteen. Fifteen among thousands. There is little hope in the political process or the politicians’ word in finding answers to Sri Lanka’s disappeared. Instead, the violence of the beeshanaya era has now found a purpose in the narratives of populist politics; a tool to invoke fear of the past and justify state violence. Mahinda Rajapaksa, in one of his final days as prime minister, addressed the nation and equated the violence (purportedly) inherent in the aragalaya to the JVP insurrection. It must have seemed especially cruel to some who had gathered when Rajapaksa in his televised address invited the youth of the country to ask their parents of what occurred during the late 80s. It is apparent that Sri Lanka’s political class sees the past as a political tool which can be repurposed, forgotten, buried but never objectively studied, taught or investigated.

It perhaps explains the efforts by the families to appeal their cases once more to the media.

It in some way can be taken to indicate the families giving up on securing justice and aligning their efforts towards ensuring non-recurrence and finding closure. All these connect to how their stories are related to by the general public. Even at GotaGoGama during the height of the aragalaya, justice for financial crimes took centre stage over human rights issues.

Where politics has exploited and the media forgotten, It is the people’s stance that tells the story. The plot of Karunatilaka’s novel provides us with a question and a contextual answer that sheds some light here.

In the case of this article, it provides both a beginning and an end.

A novel which for all its widespread acclaim revolves around the futility of a dead man trying to retrieve irrefutable proof to convince an oblivious population that his country is embroiled in an endless cycle of death, violence, hatred and atrocity.

View this post on Instagram