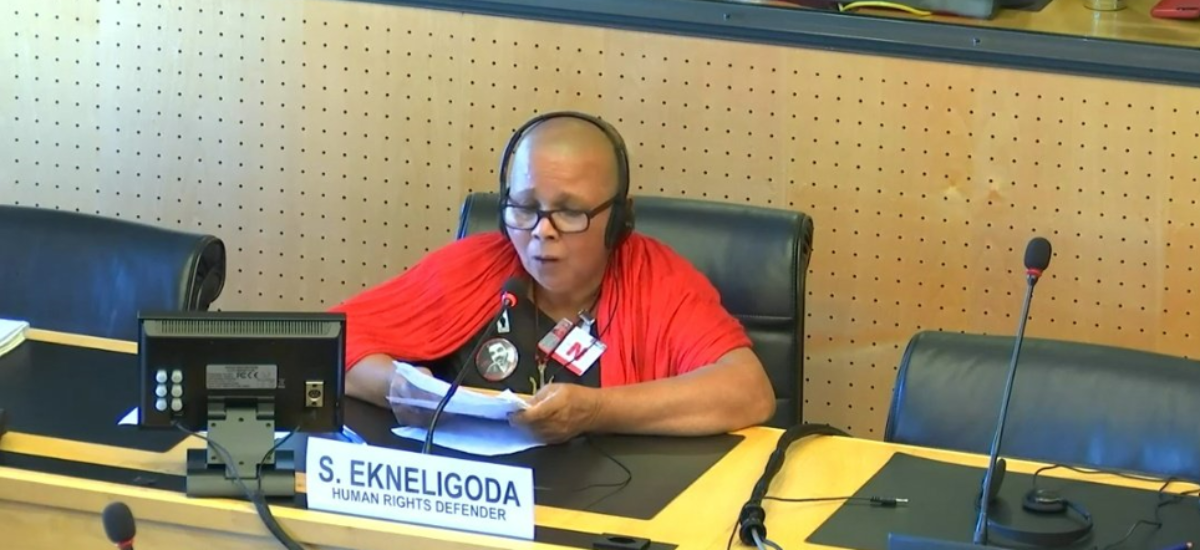

Image Courtesy: Sandya Ekneligoda/Twitter

“How many more years should we come to Geneva?” Sandya Ekneligoda, wife of disappeared journalist, at “informal” consultation on UNHRC resolution on Sri Lanka, in Geneva, 16th Sept. 2022

Among the many international institutions in Geneva is the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), set up in 2006 through a decision of the UN General Assembly (193 UN member states including Sri Lanka). It replaced the UN Commission on Human Rights. The 193 UN member states elect 47 states to the UNHRC from the states that present candidatures. Sri Lanka was a member of the UNHRC from 2006-2008, but in 2008, with mounting allegations of rights violations, its candidature to be elected to UNHRC was defeated. Since then, Sri Lanka never presented itself as a candidate to be elected to the UNHRC.

Another key UN human rights institution in Geneva is the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), with staff members led by the High Commissioner. This was set up by UN General Assembly resolution in 1993.

UNHRC resolutions and OHCHR reports

In 2009, nine days after the end of the war, the UNHRC adopted a resolution along lines requested by the then Sri Lankan government whose overall tone was to praise the government. In 2012 and 2013, UNHRC resolutions expressed mild criticism of the human rights situation and reconciliation and called for domestic measures to address concerns. In 2014, the UNHRC resolution decided to ask OHCHR to conduct a comprehensive investigation on Sri Lanka. The government vehemently opposed these resolutions.

In 2015, the government made a series of commitments towards reconciliation which were reflected in a “consensus resolution” with no voting and with the support of the Sri Lankan government. In 2021, after a new government had declared they would no longer honour the 2015 consensus resolution, a new resolution was passed through voting to gather evidence and advance accountability.

The voting on five resolutions on Sri Lanka between 2009 and 2021 indicates the dramatic loss of support for the government at the UNHRC with the number of countries supporting the government decreasing from 29 out of 47 in 2009 to just 11 out of 47 in 2021. The loss of support was mostly in Latina America, Africa and Asia, which countries comprise 34 of 47 members of the UNHRC.

The 2012 UNHRC resolution and all the subsequent resolutions on Sri Lanka asked OHCHR to monitor the human rights situation and report back to the UNHRC. OHCHR reports have captured key human rights concerns of different Sri Lankans such as the war affected communities in post war North and East with significant focus on Tamils, emblematic cases such as the Welikada prison massacre, murder and enforced disappearances of journalists and youth, militarization, COVID-19 related concerns, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, freedom of religion, situation of human rights defenders, civil society and most recently, Easter Sunday attacks and economic crimes. Reports have also highlighted institutional, legal and policy changes and initiatives, scrutinising both positive and negative implications on human rights of Sri Lankans. OHCHR recommendations have included referring Sri Lanka to the International Criminal Court and use of Universal Jurisdiction to promote accountability as well as measures like asset freezes and travel bans.

The new resolution

The highlight at the UNHRC on Sri Lanka last week was the OHCHR’s most recent report on Sri Lanka. As this has been written and talked about, I will focus on the draft resolution, which had been shared with the government and subsequently published and opened up for discussion.

Two consultations known as “informals” were held in Geneva on September 16, led by the core group consisting of a small group of countries, namely the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Malawi. Government representatives dominated the proceedings, rejecting the draft resolution. But perhaps understanding that the majority of governments at the UNHRC may support a resolution along the lines of the draft presented, the government also made proposals to drastically dilute the resolution’s text. It rejected any form of international involvement to advance accountability and reconciliation as well as reference to the commitments the then government had made in 2015 under premiership of present president Ranil Wickremesinghe and insisted that the 2021 resolution was beyond the mandate of the UNHRC. The government also claimed that the economic crisis was beyond the mandate of the UNHRC despite the UNGA resolution establishing the UNHRC explicitly referring to its mandate to promote all human rights, including economic, social and cultural rights.

States such as Cuba, Russia, China, Pakistan, Philippines, Vietnam, Iran and Ethiopia supported the Sri Lankan government position. Countries such as Ireland, Finland, Sweden, Norway, France, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Lichtenstein, Australia and New Zealand supported the draft resolution but didn’t offer suggestions towards strengthening the draft resolution.

Government representatives, including from Sri Lanka, were given priority to speak during the two consultations lasting more than three hours in total. In about 15 minutes allocated for non-governmental speakers, Sandya Ekneligoda wife of disappeared journalist Prageeth Ekneligoda, was one of the four who spoke. Recalling her travels to Geneva in search of justice for more than 10 years, she asked how many more years governments were expecting her and others like her to come to Geneva.

Strengthening the text of the resolution

The UNHRC process on Sri Lanka has seen slow progress since 2009, with landmarks being the OHCHR led investigation of 2014, government commitments in 2015 and the evidence gathering process in 2021. Hence, it is disappointing that the 2022 draft resolution does not indicate any progress from the March 2021 resolution 18 months ago.

The draft resolution as of now is very similar to the 2021 resolution with some new language to reflect the economic crisis, large protests and violations of rights to freedom of assembly and expression.

As noted above, there were hardly any proposals to strengthen the resolution. Below are some ways the draft resolution could be strengthened to better reflect the situation in Sri Lanka;

- Compliment the tasks entrusted to OHCHR with the establishment of an independent expert mechanism to monitor ongoing rights violations, progress made on accountability within and outside Sri Lanka and report back regularly to the UNHRC and to the General Assembly for two years.

- Call on the government to cooperate in the implementation of the resolution (such a call was there in the 2014 resolution, but was absent in the 2021 resolution and in the present draft).

- Call on the government to protect Sri Lankans cooperating with the UN in implementing the resolution.

- Call on UN member states and UN officials to establish protection and support mechanisms for those who may face reprisals for cooperating with the implementation of the resolution. This is essential for the implementation of the resolution.

- Use the word “economic crimes” in the resolution, one of the most significant new additions in OHCHR’s latest report.

- In referring to the importance of preserving and analysing evidence to advance accountability, make specific reference to wartime atrocities, Easter Sunday attacks and economic crimes (OP 8).

- Caution on potential negative implications on human rights due to International Monetary Fund (IMF) conditionalities when welcoming the staff-level agreement between the government and the IMF (PP 8).

- Note the importance of considering public input and work done in previous efforts of constitutional reform when acknowledging the government’s commitment to constitutional reform (PP 13).

- Call on the government to implement (not just give due consideration) recommendations of UN Special Procedures, and include recommendations made by UN treaty bodies (OP2).

- Make specific reference to student activists, trade unionists, religious leaders, lawyers, and families of disappeared when expressing concern about surveillance, intimidation and harassment of civil society and calling for their protection (OP 5 and OP 13).

- Mention the withdrawal of charges by the Attorney General and the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption in reference to undermining justice for emblematic cases, in addition to delays and presidential pardon (OP 7).

- When referring to prosecution of emblematic cases and corruption, remove the words if / where warranted as prosecutions must happen in relation to all these cases (OP 10 and 11).

- Request OHCHR to present the next oral update on Sri Lanka at the 52nd session of the UNHCR in March 2023 instead of at the 5rd session in June 2023 (OP18).

The way forward

Sri Lanka’s approach at the UNHRC appears to be to demand more time and make new promises. But promises without actions on the ground are unlikely to be taken seriously. Making and breaking promises to its people and international bodies such as UNHRC has been a hallmark of successive governments. For example, the then Foreign Minister at the last session of the UNHRC three months ago announced a moratorium on arrests under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) but three student leaders were arrested last month under the PTA and remain in detention. In 2015 the then government (with Ranil Wickremesinghe as the prime minister) had agreed to set up a judicial mechanism with foreign judges, defence lawyers and authorised prosecutors and investigators but did not even present a draft legislation to parliament.

The only way to stop or reduce scrutiny and critical commentary by UNHCR and OHCHR is to stop or at least minimize ongoing rights violations and ensure truth and justice for past violations, including wartime atrocities, Easter Sunday attacks, economic crimes, corruption and crackdown on dissent.