Photo courtesy of Global Giving

Sri Lanka has long been known for its positive human development indicators in the health sector including low infant mortality, low maternal mortality and good nutritional status of children. However, the past two years has seen a steady decline in the health and wellbeing of the majority of people as food prices rocket and there are shortages of essential food supplies.

Children are particularly hard hit. With the closure of schools for long periods children had no access to school feeding programmes while the supply of nutritional items such as thriposha had to halted for lack of funds.

It is expected that malnutrition will rise in the face of increased poverty and high food prices brought about by the economic crisis. Currently, the levels of poverty have risen bringing it to 14% from 6.7%. This amounts to 700,000 families out of approximately 4.9 million who are “nutritionally at risk”.

“Families are skipping regular meals as staple foods become unaffordable. Children are going to bed hungry, unsure of where their next meal will come from – in a country which already had South Asia’s second highest rate of severe acute malnutrition…Almost half of children in Sri Lanka already require some form of emergency assistance,” said George Laryea-Adjei, UNICEF Regional Director for South Asia, after a recent visit to the country.

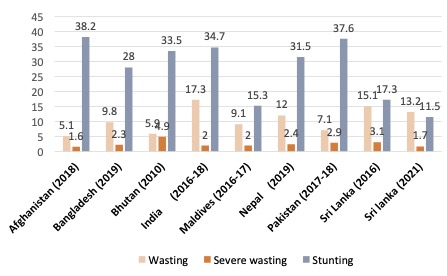

UNICEF ranked Sri Lanka sixth in underweight children under five years of age and second among the countries facing severe malnutrition in South Asia. However Health Ministry Secretary Janaka Sri Chandraguptha dismissed the UNICEF report, saying that he was not satisfied with the data used to compile it. A national survey conducted by the Medical Research Institute in 2021 found that the malnutrition status of children under five years of age had actually decreased by 13.2 percent, he pointed out.

A statement by the Sri Lanka Medical Nutrition Association, the Nutrition Society of Sri Lanka, the Dieticians’ Association and the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) People’s Forum said that before the current crisis, Sri Lanka had the least number of stunted children under five years in South Asia with a prevalence of 11.5% (Stunting denotes low height for age as a result of chronic malnutrition).

(Source: UNICEF/WHO/World Bank, Joint child malnutrition estimates country level, modeled and survey estimates, May 2022 and Medical Research Institute, nutrition status and gaps in the diet of Sri Lankans during the pre-economic crisis Period)

There are three measurements of malnutrition used to compare the nutrition status of a country and the various regions. These measurements are assessed among children under five years since all children grow in the same pattern and speed at this age as genetic differences do not come into play. Children under five are considered as the observation group of the whole population’s nutrition status. Any change in the diet is quickly reflected among children, especially of this age. The measurements are weight for age, weight for height (thinness-wasting) and height for age (shortness-stunting).

Over the past 30 years stunting, also known as chronic or long term malnutrition measured as height for age, has continued to reduce, seeing a marked improvement among children in this age group. This improvement was because the other form of childhood malnutrition, which is acute or short term malnutrition measured by weight for height, was arrested before it converted into stunting or loss of height, the group’s statement said.

The reduction in chronic malnutrition could be attributed to successive governments supporting public health programmes that arrested wasting at the right time before it converted to stunting. These measures included supplementary and therapeutic feeding for children under five, micronutrient supplementation for pregnant and lactating mothers and children of this age group and beyond, growth monitoring and promotion meticulously done, food assistance programmes and agricultural assistance to farmers.

The group called for a systematic programme of intervention targeting vulnerable households, without piecemeal approaches, on the part of state and non-state actors and urged all entities working on food and nutrition to act fast with a coordinated approach to arrest the deterioration of vulnerable families.

It recommended these interventions:

- Immediate supply of therapeutic food to approximately 27,000 children under five years who are severely malnourished.

- Support by way of supplementary feeding for the approximately 207,000 moderately malnourished children under five years.

- Accelerate the existing mechanism to early identification and correction of growth faltering of children under five years to prevent acute malnutrition.

- Household food and agriculture support should be provided to families of children who have begun to falter in their growth in order to prevent them from reducing into the pile of the undernourished. Supplementary food is also important for these children. These growth faltering children amount to approximately 500,000 as seen through regular growth monitoring reports. It is also important to identify these children on time and take necessary corrective measures very soon.

- Support the popularising of healthy and creative menus which include mixed curries and dishes, one dish meals and healthy snacks which are less cost intensive and easy to prepare.

- Identify certain food commodities that are essential in fulfilling nutritional requirements and open shops that sell these food items at an affordable price to all income groups.

- Establish and multi-stakeholder coordination mechanism to implement a multi-sector approach and action plan national and district level to address the current nutrition problems.