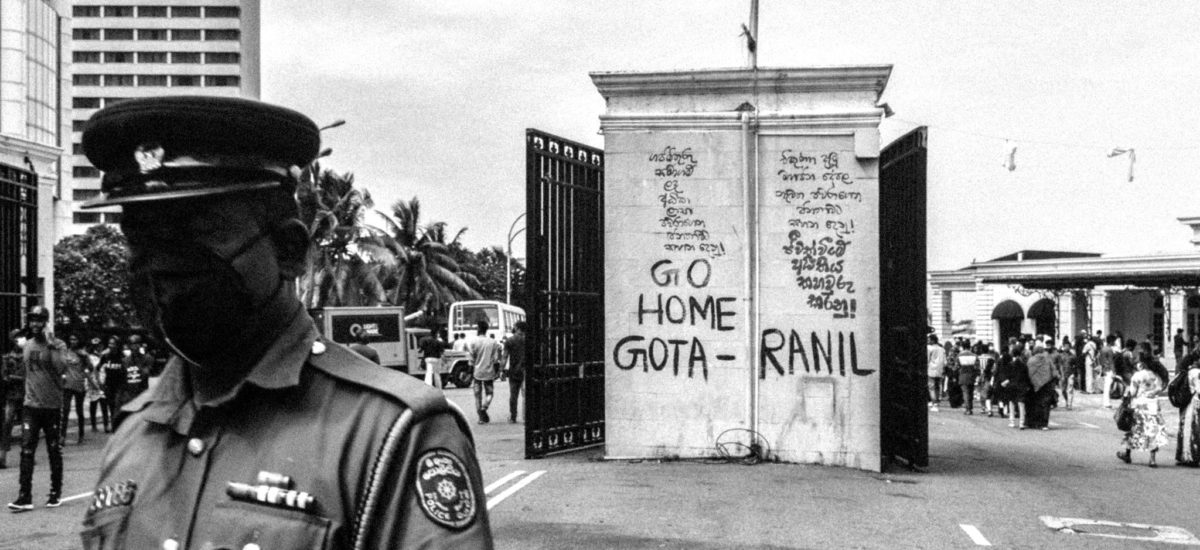

Photo courtesy of Kris Thomas

Arrests, amidst a wider crackdown on protesters in Sri Lanka, threaten progress in tackling the economic crisis. Although a show of repressive force may be intended in part to promote stability, in reality it exhibits bad governance and will lead to worsening unrest. Political leaders and their backers should learn lessons from the grim events of July 1983 – when Ranil Wickremesinghe first become well known – and their aftermath. Those seeking greater justice may also find valuable learning points in a sombre past.

Cracking down on protests while ordinary people suffer

Shortages of necessities, soaring inflation and loss of income continue to cause misery to many people. Corruption and serious errors of judgement by a harshly authoritarian ruling family and their inner circle brought about catastrophe. People from minority communities are still waiting for news of loved ones forcibly disappeared by the state or faced other forms of mistreatment. The ousting of former president Gotabaya Rajapaksa through people power was a critical moment, offering fresh hope.

His replacement, Ranil Wickremesinghe, whom he had previously chosen as prime minister to help prop up his regime, came to power through the backing of ruling party MPs – not the break from the past that many sought. The new president is widely mistrusted. Yet some people, weary after months of hardship and harsh uncertainty, are willing to give him the benefit of the doubt.

However he has so far squandered opportunities to distance himself from the Rajapaksa family’s self-seeking and repressive ways and lack of concern for ordinary people. The police and army have attacked Galle Face and other protest sites, arrested several prominent protesters such as Dhaniz Ali and Veranga Pushpika and harassed journalists. Organisations and individuals have issued a civil society statement on attacks and reprisals against peaceful protesters, condemning “ongoing attacks including violence, false labeling and legal reprisals against unarmed peaceful protesters” and calling for “an immediate end to reprisals against those exercising their constitutionally protected rights to advocate for change.”

This wave of repression has been aided by draconian emergency regulations that seriously undermine human rights, giving the state greater powers of surveillance and control, make it easier to detain people for long periods on flimsy grounds and mistreat them when in custody and increase penalties for a range of offences including same sex acts, a relic of colonial-era oppressive laws. They were endorsed by Parliament, although voted against by some of the opposition.

Former Sri Lanka Human Rights Commission member Ambika Satkunanathan filed a fundamental rights petition that challenged the declaration of the state of emergency and the emergency regulations. She claimed that the regulations restricted the fundamental rights of the people and offered powers of search, arrest, detention and interrogation that were too broad.

People may understandably have varied views about what might be the most effective way, at this point, to take action on the hardships facing so many and make ongoing progress towards a more just and equal Sri Lanka. And the Aragalaya protest movement, like any other, is imperfect. However attempts to remove safeguards against abuse of state power threaten everyone. A statement by 1,640 Catholic priests, monks and nuns on the potential arrest of Father Jeevantha Peiris warned that “both the executive and legislature are now on a repressive path.”

President Wickremesinghe has tried to drive a wedge between those who continue to protest publicly and the wider public, claiming that the unrest in recent weeks has delayed a bail out by the International Monetary Fund. This may have limited success. Yet international partners are less than impressed by a government still under the sway of Rajapaksa loyalists and unwilling to take tough decisions that inconvenience the elite so that others can survive, let alone thinking creatively about a people-centred economy. And, while the corrupt and incompetent in, or connected with, government might find it convenient to be able swiftly to silence or punish whistle blowers and critics, this hardly encourages confidence.

According to the Federation of University Teachers, “Without political legitimacy this government cannot and will not be able to stabilize the Sri Lankan economy and due to its repressive actions, it is further eroding its stock of international goodwill and therefore jeopardizing economic aid and other support the country can potentially receive.”

Indeed the Sri Lankan authorities have been urged repeatedly by international partners to abide by basic standards of human rights and democracy. For instance the United Nations Human Rights Office criticised a raid on the protest camp near the president’s office in which journalists and lawyers were assaulted. Actions such as physically attacking a BBC journalist are unlikely to give the wider world an impression of stability and reliability. US Ambassador Julie Chung called for enhanced relations and pointedly tweeted that “Our countries and our people have been friends and partners for more than 70 years, relationships that will flourish in a Sri Lanka that embraces good governance, respects human rights, and listens to the aspirations of its people.”

In what might appear a conciliatory move, President Wickremesinghe wrote to MPs inviting them to join an all-party national government to help tackle the economic crisis. He also proposed starting a dialogue on reintroducing the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, which would reduce the powers of the executive president. While some outside the dominant Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) seemed interested, others were not. As well as not wanting to let down many people seeking justice, perhaps they recognising that it could be ultimately damaging to them if they ended up sharing blame for future failures, betrayals and violations of social, economic and political rights. This might include changes to the economy, which ended up deepening the plight of the worst off while the rich and upper middle class enjoyed the benefits, and further waves of repression which may trigger wider resistance.

Remembering July 1983

President Wickremesinghe has had a high media profile in recent months. This brings back unhappy memories for some of us who are old enough to remember when he first became widely known, in the early 1980s.

He had become an unusually young cabinet member in the United National Party (UNP) government headed by his relative J.R Jayewardene and, by 1983, was education minister. The regime had become increasingly undemocratic and repressive towards members of the Tamil minority, trade unionists and others while economic reforms had been hard on many ordinary people. He was closely allied with another minister, Cyril Mathew, who openly promoted racial hatred against minorities, making out that Sinhalese Buddhists had the only true claim on the country. A pro-government “trade union” became a source of thugs who could be unofficially deployed to intimidate rivals.

In July, a carefully orchestrated wave of violence was unleashed mainly on Tamils. In often horrific scenes, some were killed (although others were sheltered by Sinhalese friends) and many more displaced. Ministers such as Mr. Wickremesinghe made it clear that they had little sympathy with the murdered, injured and bereaved and those who had lost their homes and livelihoods. In parliament he focused on lamenting the hardships that Sinhalese entrepreneurs had supposedly endured over the years while other communities were said to be given unfair advantages. In fact, many of those who suffered had been far from privileged even before the catastrophe that hit them.

The government at that time exploited what had happened to suppress some opposition parties, both Tamil and Sinhalese-led. Yet far from ushering in an era of order and stability under the ruling party, anger among Tamils at state racism, and many young Sinhalese from poorer communities at lack of opportunities, denied expression through the democratic process, turned to armed rebellion. These movements in turn descended into intimidation of, and violence against, opponents, worsening the plight of civilians.

Mr. Wickremesinghe continued to rise politically and later abandoned the extreme Sinhalese nationalism of his youth. But lack of empathy with those outside his social circle who were suffering persisted. If so sadly that was not unique.

He now has an opportunity to do the right thing and turn from the damaging path of enforcing repression and violating rights, instead embracing democracy and justice for all, although that might mean letting go of power and enabling a shift towards greater democracy. His political associates and members of the ruling or upper middle class who support him have the chance to push for an approach that is humane and prudent.

Perhaps enough Sri Lankans have discovered the effectiveness of non-violent direct action to reduce the risk of the worst consequences if and when enough people feel betrayed or desperate. But there are many risks in a scenario in which a handful of leaders hold excessive power and militarism flourishes while divisions of various kinds deepen. Fixing the current crisis will not be easy yet respect for human rights offers a solid foundation for progress to be made.

For the ordinary people too, there may be lessons to be learned. There have been moments of shared commitment and solidarity but, in the 1980s and early 1990s, all too often those who suffered in different ways and in different parts of the country did so separately or were even antagonistic to one another. Perhaps there was some sense of competition as to who was most victimised despite the degree of overlap.

To some extent this pattern remains. Part of this may be because political parties are often quite narrow in focus and mistrustful of movements over which they feel they have little control or which do not focus so much on their key concerns. But also there is a human tendency to relate more easily to those similar in identity or experience.

Certainly many Sinhalese Buddhists have grown disillusioned with the Rajapaksas and come to see that extreme racism is not in the interests of ordinary people of whatever ethnicity yet find it hard to grasp aspects of what Tamils and Muslims have been subjected to. And ethnic and religious minorities may be shut off from the plight of certain others while numerous people who are more prosperous are largely oblivious to the insecurities affecting their poorer neighbours and the risks if public services were cut or prices of basics continued to outstrip incomes, plus class exploitation and alienation.

When discrimination based on gender, caste, disability or being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender are thrown into the mix alongside individual differences, the challenges of being able to build ongoing fellowship and solidarity are all the greater. Yet the movement of recent months has opened up important opportunities: the question is whether it is possible to keep up and expand this aspect, reaching and engaging with a wider range of people and enabling them more fully to hear, understand and support one another. This may occur in parallel with practical measures to join in caring for those in most need.

Otherwise there is a strong chance that individuals and sections of the population may be picked off one by one by a state that maintains much of former president Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s contempt for human rights, sharing of power and accountability. Or militarism and a culture of violence (both the blatant kind and other sorts of preventable physical harm such as malnutrition, lack of hygiene and healthcare) could potentially spiral.

The crackdown on protesters and introduction of measures that could in future be used against large swathes of the population makes it harder to find a durable solution to the economic crisis and political instability. Those with higher levels of power, status and wealth would be wise to seek a way forward that is not at the expense of their less secure and fortunate neighbours or the situation may unravel again in damaging ways. And for others in country as well as all across the world who care about Sri Lanka, promoting mutual understanding and solidarity is crucial.