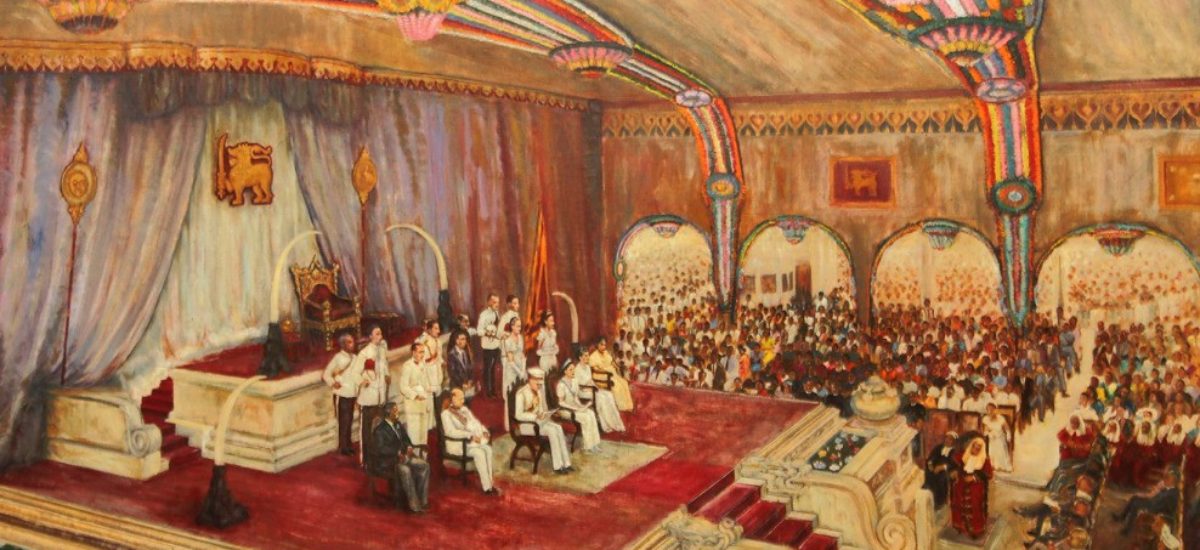

Image Courtesy: The Sunday Observer

Sri Lanka burns — and we slap on the national bandaid.

There is genuine disillusionment in the political establishment, and these feelings are valid. From COVID-19, to the 20th Amendment, to an unprecedented centralization of power and the worst economic crisis since independence, Sri Lanka faces a dire reality with no clear end in sight. We apply a bandaid to deep-seated wounds and trudge on.

Post-independence Sri Lanka tells a bloody history. As a nation, we ask if we are resilient or forgetful, negligent or complicit. We confront these questions amidst the brazen return of the Rajapaksas. As the administration backslides on promises, we puzzle over how we expected anything different.

Is it political apathy? The exodus of Sri Lankans proves concrete evidence of growing resentment towards the political establishment. But come the 2024 presidential elections, a successful voter turnout rate as seen in 2019, 2015, and years before is not unlikely.

The answer seems to lie not in political apathy, but rather the contrary: an active electoral base that is time and time again co-opted as a bargaining chip for dynasty, authoritarianism, and Sinhala-Buddhist hegemony.

As unabashed proponents of Sinhala-Buddhist supremacy, the current administration has mastered the co-optation of Political Buddhism. The political force of Buddhism is sacral. It supersedes an election season, enjoying unbroken support as a pillar of the modern state. It permeates political spaces not only through formal legislation and policies, but through its linkage to civil society. Informal relationships fund, maintain and ensure the protection of the Sangha. Sizeable donations are made via the Sangha Council, but also through private funding by political elites, parties, private sector business and civil society. Buddhist institutions intercede where the state fails, often serving as the immediate social welfare net for local communities.

Should Buddhism fall under siege, so too shall the benefits it provides. Not only as a cultural lighthouse, but as an entrenched force in civil society. And this presents a serious threat (and bargaining chip) for the zealous political mastermind.

Indeed, the Rajapaksas continue to play a foolproof gamble using the majority as a bargaining chip. A network of powerful political, business, and elite families form the foundations of unshakable, dynastic bureaucracy. Harnessing the political power of Buddhism, the Rajapaksas are buttressed by a Buddhist bloc that offers the ultimate endorsement for any despot. It bestows an unshakable, unbroken supranatural power, transforming a leader into a king or god.

Bidding for Buddhism

By 1947, British colonial rule in Sri Lanka had imposed a secular administration that sought to disestablish historic Sangha-State symbiosis. The Sangha held political legitimacy and continuity that the kingdoms of pre-modern Sri Lanka did not, while also exercising a sacral, supranatural sphere of influence over the masses. As such, the Sangha held great capacity for politicization and could potentially undermine any colonial administration. To curb political resistance, the colonial order prioritized Western secularization, particularly via the proliferation of missionary schools and the inculcation of Christian norms and virtues. Sangha-State relations were reduced to a pre-Ashokan relationship between an isolated clergy and the political realm.

Post independence, the internal forging of a cohesive national identity became a central vision for state-building. This identity was to be free of the colonial gaze; a desire to emphasize Sri Lanka as the heartland of Buddhism, and the only land of the Sinhalese, became recurrent messages in constructing the Sinhala-Buddhist character of the state. Reinstating the centrality of the Sangha and Buddhism in the state apparatus became a crucial mechanism for nation-building in post-independence Sri Lanka. Belligerent nationalism was conceived.

The Sinhala-Buddhist ethos captivated the majority. Those who enjoyed elite political and economic status under the colonial administration were quickly immersed into the new political system. The elite families who became leading political dynasties in Sri Lankan politics harnessed their Sinhala-Buddhist identity as political leverage to merge the gap between their own elitism and the general population. And despite the growing seeds of partisanship, both the UNP and SLFP emerged from a Sinhala majority and yielded candidates from an elite network of Sinhala Buddhists at the turn of independence. The 1948 Ceylon Citizenship Act, the 1956 Sinhala Only Act, and the anti-Tamil pogroms of 1956 sent a recurring message – Sinhala Buddhist hegemony, as sanctioned by the state, was here to stay.

Unlike their polarized stances on economics, the SLFP and UNP were equal proponents of policies that enshrined Sinhala-Buddhist supremacy. Thus, political actors began engaging in ethnic outbidding — a strategy whereby politicians seek to ethnically outbid the dominant majority for the favorable electoral payoffs they provide. From independence onward, parties position themselves in proximity to Sinhala-Buddhist interest while dampening their stance on partisan issues.

Capturing the voter

Political elites have an incentive to ethnically outbid their opponents by guaranteeing the success and power of unfettered Buddhist nationalism, and Buddhist militancy, in formal politics. In turn, extremist factions sacralize and legitimize the political administration.

Racial or ethnic outbidding refers to an electoral strategy whereby politicians engage in an “auction-like process” to create platforms and programmes that ‘outbid’ their opponents on the anti-minority stance adopted (Devotta 2005). Rather than appeasing minorities, politicians can maximize electoral gains by outbidding their promises to extremist factions of the majority. In Sri Lanka, securing the Sinhala Buddhist population (74.9%) will ensure an electoral victory, while advocating for policies that prioritize minorities would only target 25.1% of votes at best. Minority groups are plural themselves, and vote-splitting is probable — policies prioritized by urban groups are likely to be different to those of rural communities, and so on. Even if a portion of the majority supports pro-minority policies, it is unlikely that this would be enough to tip the vote share in favor of minorities, nor is it likely that support for contentious issues that could actually incite tangible change (such as land rights, devolution of powers, or regional autonomy) would be supported by a significant portion of the majority.

Put simply, a combination of moderate + extremist policies will always win over a moderate + pro-minority agenda. Thus, politicians can best maximize their payoffs by outbidding extremist sects of the majority — which, in the case of Sri Lanka, is represented by Sinhala-Buddhist supremacists, racist monks holding enormous political leverage, and patriarchal Buddhist institutions.

Take, for example, the 2010 elections that cemented the Rajapaksa racket. Though Fonseka carried the Northern and Eastern vote, his leniency on questions of devolution and postwar healing signalled a weak alternative to the Rajapaksa bloc. Make no mistake — neither candidate abandoned the race and religion card, recognizing the normative force that is Sinhala-Buddhist legitimacy. Indeed, both shrouded Sinhala-Buddhist fervor with vague assurances of a harmonious postwar world, omitting for whom this new world would truly serve. The “moderate” minority stance was a losing game in the face of Rajapaksa’s ethnic outbid, leading to a landslide defeat at 57% of the vote share.

Or consider 2015. The UNP-led UNFGG alliance emerged as a multi-ethnic, multi-religious coalition that outwardly presented itself as polar to the UPFA. Advocating for increased transparency, due process reforms, and support for human rights investigations became popular platforms of the UNFGG. Support for the UNFGG therefore represented a protest vote against the increasingly authoritarian Rajapaska administration, and a rejection of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism that had come to characterize its government.

But backsliding on progressive, seemingly pro-minority policies quickly ensued. Promises to investigate the Rajapaksa family under the CIABC were annulled. The government became embroiled in corruption schemes that it initially sought to demolish, and neglected any commitment to human rights investigations. The constitutional coup of 2018 exposed the UNFGG and UPFA as two sides of the same coin, equally complicit in power grabs and empty promises. Securing the majority, and outbidding the extremists, has become the recipe for political legitimacy.

Looking to 2024

In times of political turbulence, ethnic outbidding represents a sinister political tact. The current administration is flopping on promises and flailing in popularity. A disastrous economic reality confronts the nation, and its leaders offer support in the form of private jet trips, lavish parties, and out-of-touch development schemes that feed corrupt egos. They place their bets on Sinhala-Buddhist supremacy, but also on the hope of collective memory loss. For Sri Lankans to forget, to simply accept negligence and abuse as intrinsic to local politics. They wager on the ethnoreligious trump card that guarantees political longevity.

But so long as the political pendulum swings, parties will continue to ethnically outbid one another. As we sway from opposition to incumbent, it is crucial to recognize the constant force of the Sinhala-Buddhist bid.

In the case of weak states, belligerent nationalism offers a strong ideological blueprint for cohesive state-building, which binds an otherwise fractured state in the absence of effective political institutions. Appealing to nationalism becomes a primary source of legitimacy when other instruments – parties, legislatures, courts and a track record of good governance – are ill-equipped to respond to divisions within the state.

The ethnic bid will be used again. It will cloud political judgment, appealing to a more immediate, more personal cause. It will first secure the majority, and then push society to the brink of rupture by endorsing and complying with militant demands. There is no place for good governance, minority rights, devolution, land rights, and postwar reintegration efforts in this equation.

74 years since independence, and the electoral base continues to fall to ethnic outbidding. Until 2024, the best opportunity for resistance takes the form of disengaging the formal state apparatus and divesting. Feeding the divine appetite of a single leader (or family) cannot sustain our political future. How we strengthen our opposition, our local political actors, and community-based alternatives for justice will tell whether Sri Lankans will once again be a chip in a political gamble, or instead dictate the terms of the bargain.