Featured image provided by the author

“I shall wake up from these long decades of war and begin to see what we can do in peace, what sort of creature we are when the mask of lion or tiger fall from us”

Nayomi Munaweera, Island of a Thousand Mirrors

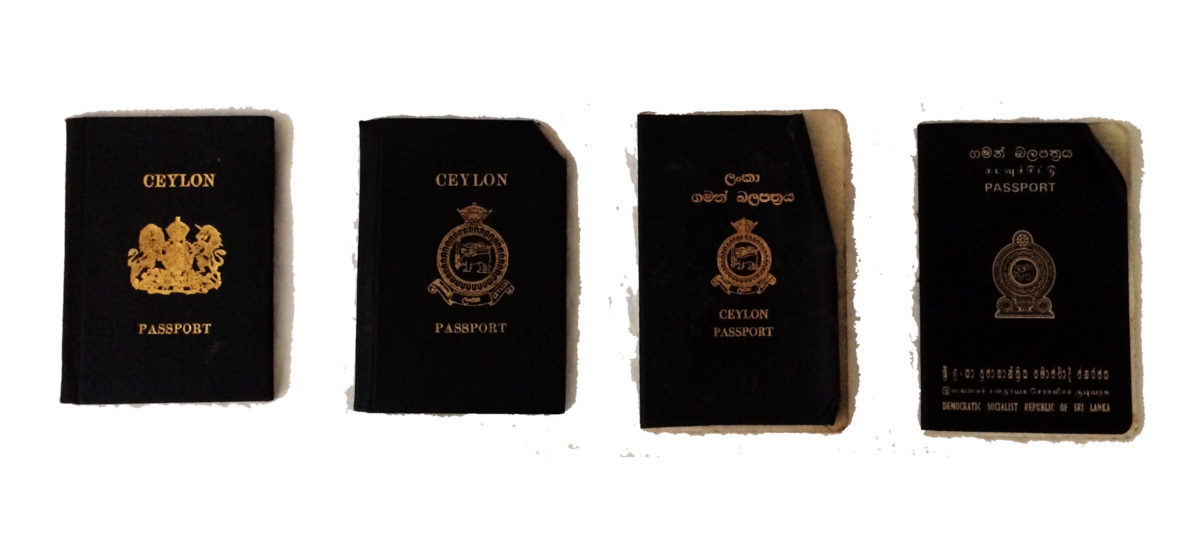

The passports I held were all similar. Bound in black worn leather; scented with that particular smell of aged books; tattered and stained with age apart from the gold stamped emblems on the front covers. A story 66 years old, to be precise.

From the British royal coat of arms, a reminder that we were once a colony, to the Emblem symbolising the Dominion of Ceylon to the familiar gold insignia of Sri Lanka we have all come to know and identify with.

This is how I became acquainted with my great grandfather, a chartered accountant by profession. A Ceylonese by descent. A Muslim. An avid reader and book collector. I never knew my great grandfather, he passed away prior to my birth, though I could picture him abruptly and lucidly through the stories told by Dada and my uncles.

This sense of urgency to learn more about my personal history was a result of the rise of anti-Muslim rhetoric at the beginning of the year 2013, which escalated into riots the following year. Reflecting on it now, I think I was looking for some sort of proof that I belonged here. I remember Mama and I having a (hypothetical) argument on migrating to another country to avoid any future riots. Her priority was the safety of her family (understandable given that she bore witness to the atrocities committed in her predominantly Tamil neighbourhood on 23rd July, 1983). Her pleas were urgent, insistent and to her, justifiable, while being completely blown out of proportion and absurd from my point of view. Yet, for the first time in my life, I felt like a second class citizen. It was the strangest feeling. Call me naive, but I had never considered myself as an immigrant or an outsider. Why should I? I was born here as were my parents, my forefathers before them and so on. Sri Lanka is the only home I know.

Since my time here, I have come to know fragments of multiple Sri Lankas. Memories from my early childhood. Long walks with chooti akka to the Appa kadey. The fiery sky caused by an oil tank bombing which made us pack our bags overnight and seek shelter at my grandmas. The long serene hours spent at art classes in the Gothami Viharaya dharmasalawa. After school shenanigans playing Tharadi and Adi kuthu with the neighbours down my lane. Early morning chapel visits with my school friend. This Sri Lanka was one of pluralism. Or so I thought in my childish naiveté.

Fast forward two decades, and I am faced with a Sri Lanka that glorifies gentrification at the price of demolishing the identities and social memories of entire communities. This Sri Lanka reminds me of those paper origami fortune tellers we used to make at school; systematically selecting memories deemed worthy, discarding the rest and then asking us to choose from these dictated choices. The absurd assumption that somehow there is a monopoly on truth. A Sri Lanka keen to transform into a sort of glamourous paradise, rebranding its own landscape. Whitewashing the past.

This island is a journey through time. Tattered at the seams like my great-grandfather’s passport, pages heavy with over 20 million narratives and histories, each of them precious. This is the legacy we inherited. The story of our genesis. It is time these stories are told and for once, for all of us to really listen.