Sri Lanka’s separatist war was one of the longest insurgencies of modern times. It was also one of the most destructive insurgencies in the region, causing the deaths of tens of thousands of combatants and countless civilians and destroying property worth billions of rupees. A war of such duration and impact should have been a goldmine to military historians and researchers, yielding countless papers, scholarly articles and monographs. Yet, to date only a handful of books and research articles have been written on the military events of Sri Lanka’s savage internal conflict. The few that have been written in English include several histories of the military conflict as well as a few specific studies and some memoirs. There are also a few studies that would rank as official and semi-official histories of the different forces and corps. More has been written in Sinhalese but whether any of these amounts to serious studies is arguable. The IPKF’s brief involvement has received more attention from Indian historians than what Sri Lanka’s long war has gained from students of the country’s military history.

The reason for this is partly a lack of interest among academics. Sri Lanka has few if any historians who have an interest in military history. There are people with an interest in military history but whether they are historians is arguable. Foreign academics have shown some interest but access to sources seems to be a major issue. The problem with a lack of literature on the war is that there is little that researchers can depend on at the start of a study. Mapping out the sources itself becomes part of the research.

But perhaps the biggest obstacle to studying the war is that the story of the war is already ‘known’. There is already a dominant narrative of the war in the South. With slight variations it runs as follows:

The separatist war was started by the Tamil terrorists who had their eyes set on a separate state. The majority of the Tamils were not supportive of this but they had little choice but to submit to the terrorists out of fear. The brave Sri Lankan forces struggled against heavy odds, including international betrayal, lack of political will and financial constraints. The terrorists were never interested in peace and always used the genuine efforts by Sri Lankan governments to strengthen their position. Finally, after 2006, under a strong political and military leadership, the brave Sri Lankan troops vanquished the enemy and brought peace to Sri Lanka. The final campaign was a humanitarian mission which was conducted with little harm to the civilian population in the North.

This narrative has been created and sustained largely by state propaganda and the mainstream media which has been firmly behind the state in its drive against the Tamil separatists. As such, it is a narrative that is based largely on the uncritical acceptance of government communiqués and reportage that confirms rather than challenges Southern prejudices and assumptions. Post-military conflict, this narrative has been generally accepted in the South as the history of the war. Interestingly, many military officers and soldiers also subscribe to this view, adhering to it so faithfully to it that one is often left wondering if their version of events had been scripted by one of many ‘war correspondents’ responsible for ‘telling’ the story of the war, especially during the final years of the conflict.

As a consequence, writing about the war is now little more than filling in the voids of this story and fleshing out the details if there are any arguments or disagreements it is about the role of individuals and regimes, not about the general conduct of the security forces or the validity of the key assumptions that sustain the story. And the possibility of a different perspective or reading of the entire military conflict is rarely, if ever, considered. Using the methods of historical inquiry to investigate the causes and courses of events is almost non-existent. After all, why bother to investigate a story that is already known? Besides, there is also the risk of challenging the dominant narrative and raising the ire of the powerful guardians of that narrative.

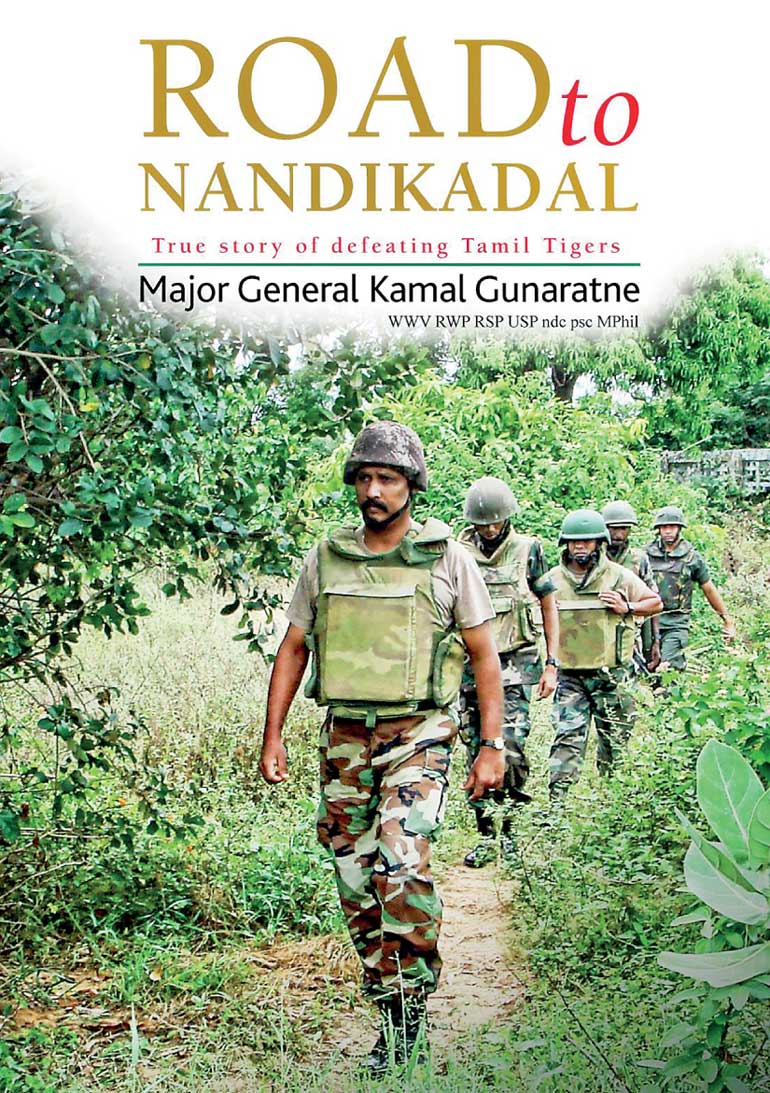

Major- General Kamal Gunaratne’s memoir The Road to Nandikadal (Author publication 2016) is another attempt to reinforce this dominant narrative with a first-hand account given by one of the key figures in the war. Armed with the authority of a key military leader in the drive against the LTTE, the author takes us through the history of the military conflict, providing a fairly detailed and often stirring, narrative of the main military events. Naturally, the operations he took part in receive greater attention and as a result the reader is treated to very detailed and graphic accounts of some events. But the tenor and the focus of the work are that of the dominant narrative. There is no doubt as to the righteousness of the security forces mission and the perfidy and the cruelty of the enemy.

In this sense, the strength of the work lies mainly in filling in the details of the dominant narrative with the authority of a first- hand perspective. Events such as the loss of Mankulam in November 1990 and the successful defense of Silvathurai in 1991 in which Gunaratne took part are described in great detail and for the first time. The final phase of the war in which Gunaratne played a major role also receives considerable attention but there is little that has not been written before – except the details of the fighting. Even the account of the death of Prabhakaran hardly deviates from what has been generally accepted since the end of the war – that the Tiger supremo died in a shoot-out with the security forces in a mangrove swamp. The author’s tactical and strategic assessments are also worthy of serious attention, as he was well-placed to make them. Such is his observation that the LTTE made a serious strategic miscalculation by not attacking the Vanni before the army could focus on the region in 2007. Naturally, there is nothing about the fate of Prabhakaran’s son, Balachandran. Nor is there anything about the deaths of civilians in the final phase of the war. That is not part of the dominant narrative.

In short, the great strength and weakness of Gunaratne’s work lies in his ability to add details to an already ‘known’ story. On the one hand there is a lot that is new but on the other hand the new details tell the same old story.

To be fair to Gunaratne we must grant that one cannot expect a retired army officer to speak as openly and candidly as we would like him to about the events of the war. And he is not a historian and is writing only about what he has experienced. However, if his pronouncements following the launch of his book are any indication Gunaratne is also a firm believer in the dominant narrative. He has also tacitly admitted to the sanitized nature of his narrative in a media interview by saying that he has only told the public what the public needs to know. It is evident from the book that he is not talking only about revealing military secrets.

Here is a sample of what Gunaratne wants the public to know, and think, about the LTTE leader Theepan and by extension, the LTTE itself:

When my soldiers carried the body of Theepan up to me, my joy knew no bounds. Theepan had led all the battles in Muhamalai against my troops while I was commanding the reserve force of the Air Mobile Brigade and thereafter as division commander of both 55 and 53 Divisions. In the Muhamalai battles he commandeered his terrorist cadres to inflict indescribable destruction on my soldiers. The highest number of soldiers to be killed and injured in the entire history of the Ealam war was in Muhamalai and the carnage was led by Theepan throughout. He gave leadership to battles which caused injuries to thousands of our soldiers who will live for the rest of their lives without legs, arms and other body parts, or lie helpless for decades unable to get off a bed or chair, wishing they were actually dead. The heartrending images of the slaughtered bodies of our soldiers and the wounded, wailing in unbearable pain, all caused by the murderous actions of Theepan, flashed through my mind like a movie. Looking down at the body of Theepan, the deadliest and most evil man at my feet, I remember having only one wish, that one day, the terrorist leader Velupillai Prabhakaran, the person behind the carnage, the mastermind responsible for the massacres unleashed on our nation for decades, and the devil personified, who victimized thousands of our soldiers and countrymen, would also one day soon, lie at my feet. (pp.691-2)

One can appreciate the relief and joy Gunaratne, and indeed all army officers and soldiers, may have felt at seeing the body of one of their arch enemies. But to call him evil for killing his enemies in battle is unprofessional and shows how the dominant narrative is skewed. The verbose style is also typical of the author’s pitch to a public that is yearning for the injection of another dose of triumphalism.

The problem with the dominant narrative is that it is filled with assumptions that are untested. I have no doubt that Sri Lankan troops have behaved with remarkable courage and resilience on many occasions but was it only they who were brave? And was it only the enemy who behaved like bloodthirsty murderers at times? Was it only the Sinhalese in the border villages who quaked with fear? And were Tamil people simply hostages of the Tigers or was their relationship with the ‘terrorists’ more complex? When we have a sanitized story that is not challenged or is not allowed to be challenged by interrogating its key assumptions, what we have is little more than propaganda.

But those who have done a little more than reading and listening to the mainstream media and those who can read between the lines in the copious reportage of the war know that there is more to the story of the war than the official, sanitized version. There is enough evidence in the mainstream media itself to suggest that there is a lot more to the Ealam war than the ruthlessness of the Tamil Tigers and the bravery of the Sri Lankan troops. That the Sri Lankan forces behaved atrociously towards civilians in the north especially during the early years of the war is fairly well documented, and disappointingly, largely ignored by Gunaratne. We also know that bravery, like cruelty, was not the monopoly of the Sri Lankan troops and that the Tamils were not always passive participants in the war. There is enough evidence to show that the Tamil Tigers did not exist in a social and political vacuum – they were the sons and daughters and sometimes guardians of the people of the North and the East -and that the people in the North and the East, like any population caught up in events which were not always their own choosing, negotiated their survival with both warring parties. Such threads are missing from the dominant narrative and few, if any attempts have been done to follow them and explore competing narratives of the war.

Interestingly, Gunaratne’s book also inadvertently provides hints of the existence of alternative narratives. At one point he describes the extraordinary means used by LTTE cadres to reconnoiter military positions at Muhamalai. “One way was to lie flat on a raft and paddle out to sea from a point about one kilometer out to sea, then turn north and while maintaining a gap of about one kilometer between the raft and the beach they would paddle another 6-8 kilometers towards kadaththane area and land surreptitiously on the beach” (p. 634). This was no doubt a superhuman effort and would have been lauded as an act of exceptional bravery and courage had the cadres been Sri Lankan soldiers and placed them among the ranks of the ‘ greatest of the great”, an adulation Gunaratne reserves for the commandos and the special forces of the Sri Lankan army. The last stand of the Tiger leadership as described by Gunaratne, will also surely rank alongside similar acts of defiance by Sri Lankan forces. And we are also told that among the LTTE dead were cadres who had prosthetic limbs, a sign of a fierce commitment to their cause which, to his credit, Gunaratne acknowledges in a rare recognition of the enemy’s grit. They remind us that the vanquished too have their stories and their causes.

The persistence and constant reinforcement of this dominant narrative is a reflection of the continuing the North-South tensions despite the destruction of the LTTE. The ‘Terrorists’ have been defeated but the fear of the enemy remains. This insecurity is partly due to the activities of the Diaspora to exert a pressure vastly disproportionate to its real strength. Along with that fear is the urge to assert control over the vanquished North that once spawned the ‘terrorists’. It is due to this tacit admission of the past relationship between the Tamil people and ‘terrorism’ that the dominant narrative feels the need to deny that very connection and to diminish the humanity of the enemy by reducing all their actions to mere terrorism. Forcing the enemy into the straight jacket of ‘terrorism’ itself is a means of keeping the Tamils in line by reminding them that any sympathy for the enemy or any recognition of their own in the ranks of the enemy runs the risk of being identified as terrorist sympathizers. It is a sign of a lingering fear of the beaten Tamils and a desire to keep them cowed. It is a crude way to keep the peace and avoid another war and certainly does little to enhance our understanding of the military conflict and its causes.

At the same time the narrative that dehumanizes the Tigers also robs the Sri Lankan troops of their humanity in a different way. Just as the Tiger cadres are branded terrorists the Lankan troops are lauded as war heroes with an implied infallibility, particularly when it comes to dealing with Tamil civilians, and whose bravery in battle is generally unquestionable. It is a notion which Gunaratne does a lot to promote and which is readily embraced by the public as it comes from a respected war hero himself. It does not bode well for the reputation and professionalism of the armed forces for the shortcomings of their members to be glossed over or ignored. And soldiers who are above reproach are the stuff of hagiography, not military history.

For the military historian the utility of Gunaratne’s book lies in its key strengths. The detailed descriptions of some of the military operations coming from someone who was in the thick of them are reliable and useful. So are the author’s strategic and tactical evaluations. But at the same time, Gunaratne’s work also reminds us of the continuing poverty of the historiography of the Ealam Wars and the need to enrich it by asking questions rather than simply accepting feel-good narratives. In Gunaratne’s work the old story has been repeated, albeit in greater detail and color providing few new insights and without raising any questions that might upset the official history. The immense popularity of the book suggests that the public likes what they have read, which augurs ill for the reception of anything other than the same old story in the future. The book also reminds us of the need to be cautious when reading first-hand accounts if the authors are too close to the causes behind the events they are describing, and that the history of the Ealam War is too serious a subject to be left to former military officers.