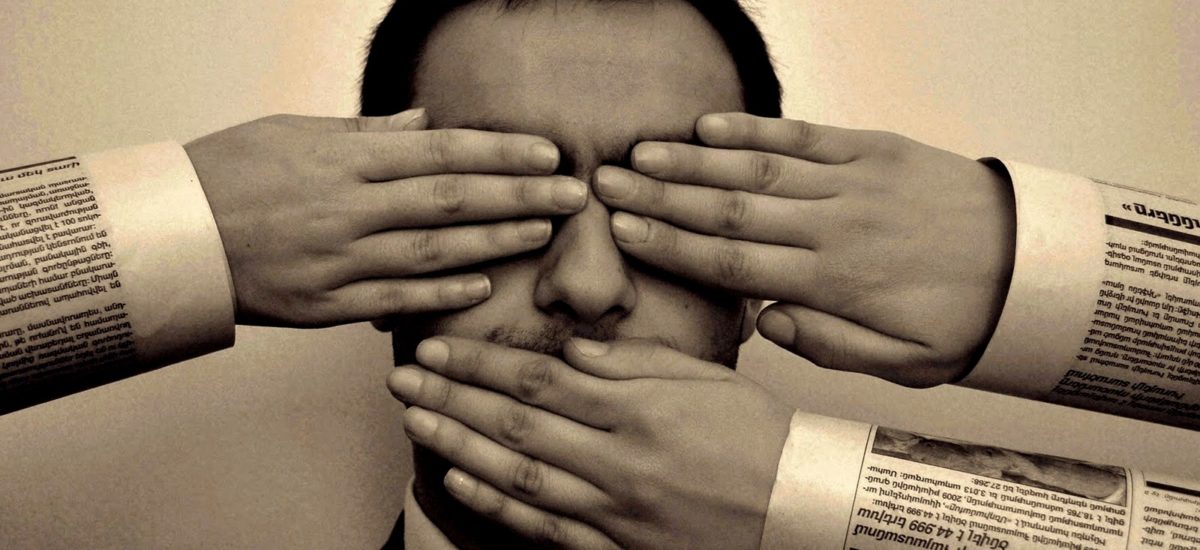

Featured image courtesy NewsFirst

Former editor in chief of the Nation in Thailand, Kavi Chongkittavorn received an unexpected scoop when visiting Sri Lanka in the 1990s. The source – Minister of Foreign Affairs Lakshman Kadirgamar, who challenged, “If I give you stories… stories which involve Thailand, will you write them?”

Chongkittavorn replied that it was his duty to do so. The subsequent story he filed – revealing that Phuket was being used as a base for the LTTE to smuggle weapons to Sri Lanka – surprised Kadirgamar, who never thought that he would write a story implicating his own country.

“He thought I would never write the story as something might befall me. But a good story is a good story,” Chongkittavorn says.

Kadirgamar could be forgiven for thinking Chongkittavorn would fear for his safety – since 1992, 19 journalists have been killed in Sri Lanka in the pursuit of their jobs, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Many of these cases are still unresolved, as Groundviews has reported in the past.

This is pertinent to remember as World Press Freedom Day fell on May 3. However, Chongkittavorn says he has seen a vast improvement since his last visit.

During the era of Mahinda Rakapaksa, the former editor in Chief of the Nation said, media freedom ‘had been turned upside down, including media structures.”

This isn’t the case today.

“Journalists are not being jailed, or murdered, or kidnapped. I think the [Sri Lankan media landscape] has changed a lot since the new government,” Chongkittavorn said.

He’s not alone in thinking so. Sri Lanka has made significant gains in the World Press Freedom Index, compiled by RSF, ranking 141 out of 180 countries in 2016 compared to 165 the previous year.

A recently published report by Freedom House noted that Sri Lanka had made major gains in media freedom, unlike many of its neighbouring countries.

“Journalists faced fewer threats and attacks than in previous years, investigations into past violence made progress, a number of websites were unblocked, and officials moved toward the adoption of a Right to Information bill,” the report noted.

However, Sri Lanka remained purple – classified as “Not Free”.

Speaking at the launch of “Rebuilding Public Trust” a report led by the Secretariat for Media Reforms in collaboration with International Media Support, assessing Sri Lanka’s current media landscape, TNA MP R Sampanthan said there was a need for “courageous, fearless, independent and objective” journalists, particularly now that the country was in the process of creating a new constitution.

R Sampanthan speaking about violence against journos at "Rebuilding Public Trust" #lka #SriLanka #WPFD2016 pic.twitter.com/m5Ie311QYZ

— Groundviews (@groundviews) May 3, 2016

On a somber note, he pointed out that 12 journalists had been killed in the Northern Province in recent times.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, commenting on this, added that it was ‘an unpleasant truth’ that the people of the South didn’t care about the plight of Tamil journalists, seeing them as different.

Chongkittavorn thinks that this mentality needs to be changed. “I think journalist’s number one priority now is to promote awareness… so that the Sinhalese and Tamils understand they have to spend their lives together. There is a need to create a shared destiny, and journalists need to write stories that share that vision, while writing in a way that reflects reality,” he said.

However, there’s a long way to go before this can be achieved, since Sri Lankan journalists mostly look inward, at their own government, instead of linking with the rest of the world. “Sri Lanka is not alone. There is a lot that can be learned from other countries, especially those in the South East Asian region.” he adds.

#lka media facing a huge challenge: Kavi Chongkittavorn #SriLanka pic.twitter.com/8vmLwuPUnA

— Groundviews (@groundviews) May 3, 2016

Key among these learnings is Thailand’s Freedom of Expression legislation – Thailand was the first in the ASEAN region to adopt such legislation. World Press Freedom Day this year also marks the 250th anniversary since freedom of information legislation was first passed in Sweden and Finland.

Journalists should be able to access the information they need in as short a time as possible. “In Thailand and Indonesia, it’s a long process. Ideally, the time should be less than one week. Not one month, or three months, as in the case of Thailand,” Chongkittavorn said. The state should also proactively disclose sensitive information in the interests of transparency, including the granting of tenders, he said. Most surprisingly, the former editor revealed that many journalists did not choose to make use of the legislation, in the interests of time. In fact, since the passage of Thailand’s freedom of information legislation, just 2% of all journalists had made RTI requests. The majority of requests came, ironically, from government officials, who wanted access to assessment reports, particularly from the Ministry of Education.

“We have to increase awareness, too, that freedom of information is for everyone. It’s not just for journalists. It is for the wider public, so that they know what’s going on. Keeping national secrets on issues should be the exception, not the rule,” Chongkittavorn said.

Minister of Mass Media and Information Gayantha Karunatilaka meanwhile said that the government hoped to debate the RTI Bill in Parliament next month. Speaking about the media culture in the past, he said it was a ‘moot point’ whether the current media culture could positively contribute to political and social change. “We have failed so far in creating a coherent media culture of mutual understanding and reconciliation between ethnic communities, post-war.”

While expressing hope for Sri Lanka in terms of media freedom, Chongkittavorn also had concerns on how polarized many journalists were. “Sri Lankan media are very colourful. Many journalists also write with a fixed mindset. It’s important to keep an open mind. Apart from the ability to write good stories, sticking to the facts and timeliness is so important. Most journalists want to be the first to break a story. I took a different approach to most, which is why I have continued in the field for such a long time,” he said. “Most importantly, journalists need to be intelligent, understand the dynamic, and ask themselves why they got into the field. It’s not about the spin.”

These sentiments were echoed by many speakers at the event on Press Freedom Day, particularly Prime Minister Wickremesinghe, who lambasted sections of Sinhalese media for fear-mongering and branding missing journalist Prageeth Eknaligoda as a supporter of the LTTE.

While Sri Lanka has made strides forward in terms of media freedom, the battle isn’t over – many of the cases of journalists killed or missing remain unresolved. In addition, as human rights activist Ruki Fernando pointed out, journalists in the North were threatened and assaulted recently – although many of these incidents were later amicably resolved. In an amusing fracas, the Secretary to the Media Ministry issued a circular with some “advice” on reporting on the Opposition – with Prime Minister Wickremasinghe having to intervene on the issue.

However, this Press Freedom Day, it was interesting to note that the focus was on reconciliation and moving forward, rather than solely focusing on the past.

So what will the media landscape look like in 2016, and beyond?

“Rebuilding Public Trust” notes the continued importance of civic media, stemming from a time when many were too reticent to voice their opinion on traditional media. In the 1990s, Sri Lanka saw a new phenomenon – blogging, which arguably birthed citizen journalism. As time went on, the rise of social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter and even WhatsApp and Viber became a source of news.

As Krishan J Siriwardhana of the University of Colombo Journalism Unit notes in the report, “Media consumers had a very limited opportunity to convey feedback, share their views and comments in traditional media due to the inherited characteristics of newspaper, television and radio. Websites, blogs and social media have not only given the opportunity to its users to comment and share their thoughts, but also users are given the opportunity to generate their content as journalists.”

This has led to interesting changes in the media landscape – for instance, incidents which might not the reported in mainstream media will often be highlighted on social media or online. Scrolling through your Twitter feed, for example, you will find everything from details of a train delay to stories of tragic road accidents, and even news and analysis – all from citizens reporting on issues that matter to them. As more people move away from the printed word and towards their computer or smartphone, it seems certain that this new breed of journalism is here to stay. Will the new government welcome this new breed, or regard it with suspicion? Earlier this year, the Media Ministry called on news websites to register, decreeing that those who didn’t would be deemed ‘unlawful’. This demonstrates a woeful lack of knowledge about the nature of social media, where anyone with a smartphone can report the news. It also restricts the potential of civic and social media as an equal playing field. However, the new report handed over to Government ministers called for self regulation, including through the Code of Professional Conduct – which is an encouraging sign.

As Deputy Chairman of the Board, Sri Lanka Press Complaints Commission, Sinha Ratnatunga says, “Neither the Editors’ Code, nor the Press Complaints Commission of Sri Lanka are the ideal. There is, no doubt, room for improvement. But the principle of self-regulation remains steadfast and true. The alternative – a statutory body of Government appointees is not the answer. It is a sine-quo-non for a Free Press in Sri Lanka, or what is left of it, that its well- being is in its own responsible hands. It is up to those in the profession, and the industry, to protect it and foster it in their own interests and in the interests of their countrymen.”