Featured image courtesy the author

There is a place, unassuming and quiet on the pristine Southern coast; white sand fringed by blue sea under the shade of an unbroken line of coconut palm trees.

Weligama, ‘sandy town’.

There is a place, hidden and hiding a few miles inland from the Northern shore; palmyrah grows in the scorching sun and vines entwine abandoned houses.

Valikamam, ‘sandy town’.

They look nothing alike; fine white dust covers the shores of one and hard-packed red dirt fills the land of the other. But at the very heart of what gives them identity – their mark on a map, the words that string together to form their names – they are very much the same.

As are these two men, who, at first glance and after a few assumptions coloured by social stereotypes, one would never assume to have anything in common. Not only do they speak two different languages, they also reside hundreds of miles apart, virtually on two different ends of an island and for the most part have known two different ways of life.

One wears a well-worn sarong and shirt as he makes his way to the small school he teaches at every morning.

The other dons the sharp creases of a pilot’s uniform before taking to the skies to his destination for the day.

Their dreams – to feed, clothe, educate and raise their children to be the best they can be while protecting them from all harm – are the same.

And so are their nightmares.

In the dark of the night, lying on his mat on the cold floor of his simple house, he shakes in a cold sweat. Ears filled with noises that have plagued his sleep for seven long years.

In the blinding light streaming through a hotel window in a country far from his home, he stares into nothingness.

The fevered sparks of the last two decades flashing on the inside of his eyes.

When uniformed men drove into his village a month ago, slowly cruising past houses, stopping for longer in front of some, he could feel his heart cease to beat and the blood drain from his face. His breath remained caught in his throat until the wheels sped away, their dark armoured bodies snaking through the tall palmyrah trees that sheltered his home.

He watched one news story after the other about planes shot down – both by accident and targeted for destruction – and the forces behind their end. Hijack, crash landing, nosedive; terms his friends gasped at, terms his colleagues knew better than to bring up in his presence, especially before takeoff. His expression remained unreadable as he took his place in the cockpit.

He wished he could tell someone these nightmares, the sights and sounds that deigned to invade his thoughts even when he did something as simple as cycling into the kovil in town at the start of the day. No one ever said anything; those who didn’t know assumed his stint in a state-controlled rehabilitation facility had miraculously vanished all the physical and emotional scars he carried and those who did know were too afraid, assuming him to be far beyond repair.

He’s sat in the interview chair at human resources year after year, as was protocol, and year after year his evaluation proclaimed a clean bill of health in both mind and body. Walking out of the office and onto his next flight, he recalled his wife’s tearful voice whispering the curse ‘PTSD’ in a hushed conversation to his sister over the phone before she too, like him, chose to erase this option before it became real enough that she had to admit and accept it.

His smiles were reserved for his family and the villagers that knew and shared his pain because it was so similar to theirs. He was wary with them otherwise, maintaining an unreadable expression between seriousness and disconnect whenever he was forced to talk to a journalist who didn’t understand the depth of the questions they were asking or a politician who didn’t understand the damage of the promises he was making, ones that he was destined to break.

He went places because his wife pleaded with him, stepping out to be entertained at lavish parties with extravagant friends, nights that most usually left him drained. He preferred to be surrounded by peace, reading stories to his children or taking walks through chilly hilltops with his family, far away from people and their feigned, misunderstood pity.

He didn’t read the newspapers anymore, but he knew that people who came to speak to him always published articles on his meagre lifestyle, using him as a prop in their harangues to either praise or criticise one state actor or another. Ideally he wouldn’t want his children to remember the darkness of his past in this manner but it was only a matter of time before it cast its shadow upon them. The stories preferred to leave out the fact that his hairs stood on end at the sound of a loud noise, or when he heard his child scream, only to realise later that it was the makings of delirious laughter at having been caught while playing hide and seek. Then again he never spoke of this, so maybe he was dictating his story to them in the way he preferred – eliminating the painful details so he could suffer them in silence.

An award sat on a shelf in the house he had built for his family – the gold, gleaming along with the clean lines of metal, glass and concrete that constituted his home. He remembered the solemn yet celebratory speeches, the fanfare of a thousand camera flashes and the president’s smiling face; he also remembered rushing home, tossing the statue aside and sitting under the scorching water of a hot shower, washing away the guilt that the unnecessary pomp had added onto the weight he already carried on his shoulders. His children’s inquiring eyes when he suddenly slumped into bouts of silence, staring into the distance, the one reminder he needed that he had to live for someone else now, that his wounds had to be nursed in a way that didn’t cause any injury to them. Even if it meant sacrificing his healing.

He had heard one social worker after another translate his story to visitors; fair-skinned foreigners who knew not the languages of his country and brown-skinned brethren, who understood what the nation spoke, they just didn’t understand him.

‘This man, oh his is a sad story. It starts with the fact that he was once in the LTTE, I know, it’s very difficult to find many of them who are willing to speak. He says he is now a teacher in a school close by, but he doesn’t want to tell you what he did for them, better left unsaid I think. Please don’t take his photograph, he doesn’t want to be identified. As it scaled to a close, he wished more and more that he was just a civilian like the rest of his village, not a recruit carrying the weight of the cause on his head, because he loathed their actions in combat. The shelling left this shrapnel lodged in his leg, debris from weapons that the government swore they never ever used. He says the same attack blinded his daughter. Most of his wounds, the ones you can see, he say came from the first two years of ‘peace’. Yes yes, the government rehabilitation camps. Yes. Now you know what they were really used for.’

He overheard the whispers of a colleague who thought he was asleep on their ride home from the airport, telling a new attendant the story behind their brooding pilot, who smiled but always seemed to prefer solitude.

‘He was serving in the air force long before he joined us, for most of the twenty-six years. He left when things started escalating towards the end. No, not abandoned as much as he had an…accident. He was flying in from the East, meant to land and unload supplies, when he found himself in an ambush. What was supposed to be a deserted strip of seashore was teeming with armed vessels. When they opened fire…it’s a miracle he stayed alive and wasn’t killed mid-air. Apparently his plane crashed into the sea and ran aground on some rocks close to shore. The two others with him in the plane didn’t make it, one was hit mid-air and the other crushed when it hit the rocks. He was the only one who survived.’

Main points covered, they thought as they listened to what was being said about them. The highlights of their stories were painted in black and white, drawing up the crucial incidents that when strung together completed the experiences that made them who they are today. Facts and figures checked out. That elusive grey area was the issue.

Missing was the detail that he couldn’t take his kids to play by the seashore without panicking when they ran out of his peripheral vision.

How he looked in doubt at the strapping young lad who courted his daughter, questioning if they’d once been linked to the same movement and how badly he wanted to protect his child from his past.

How sitting behind the wheel of an airplane sent shivers up his spine, drowning out an orchestra of memory in his head as soared through the air on every flight.

They failed to mention that standing on the edge of that bridge brought tears to his eyes every time, his blood pumping at a rate that could not be safe.

Paranoia when he was close to the ocean.

Misery that overcame him near that lagoon.

They both hated the water.

An ex-rebel from the North East and an ex-officer of the armed forces, born in the South and raised in the West. Everything about them screams boundaries, polar opposites that don’t meet at a central point on any axis. Yet the cold sweats, the sleepless nights, the ghosts that gleam brighter in the tropical sun tie them together with something far from fragile. War can’t distinguish between one fighter and another before it casts its darkness on someone’s life. Trauma doesn’t differentiate when it exerts its painful force.

Divided by the lines of conflict, united in suffering its aftermath.

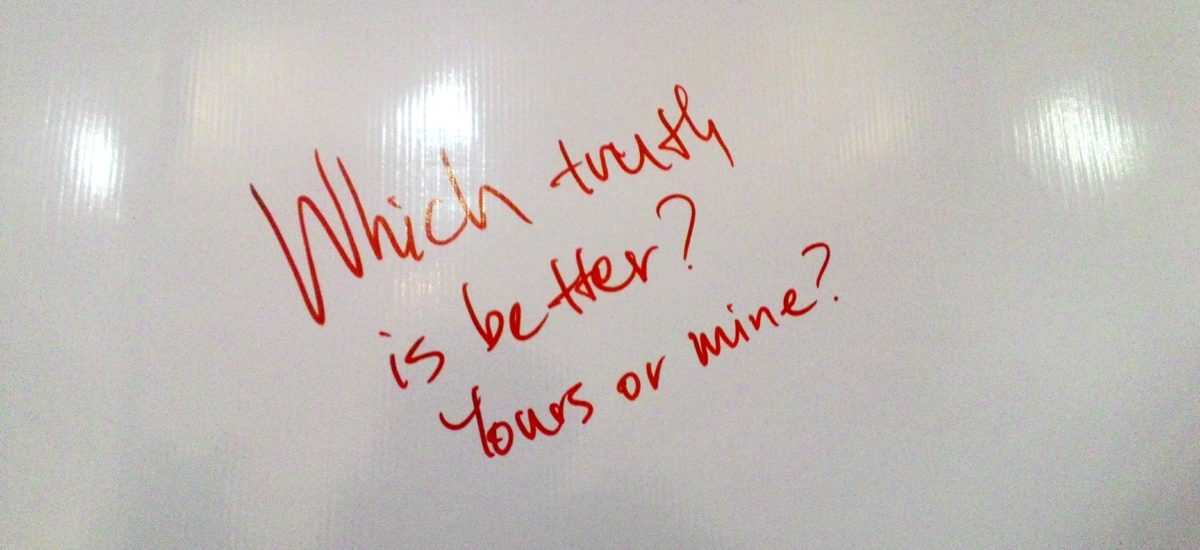

Two different sides of the story converging to the same lingering truth.

[Loosely based on true stories.]