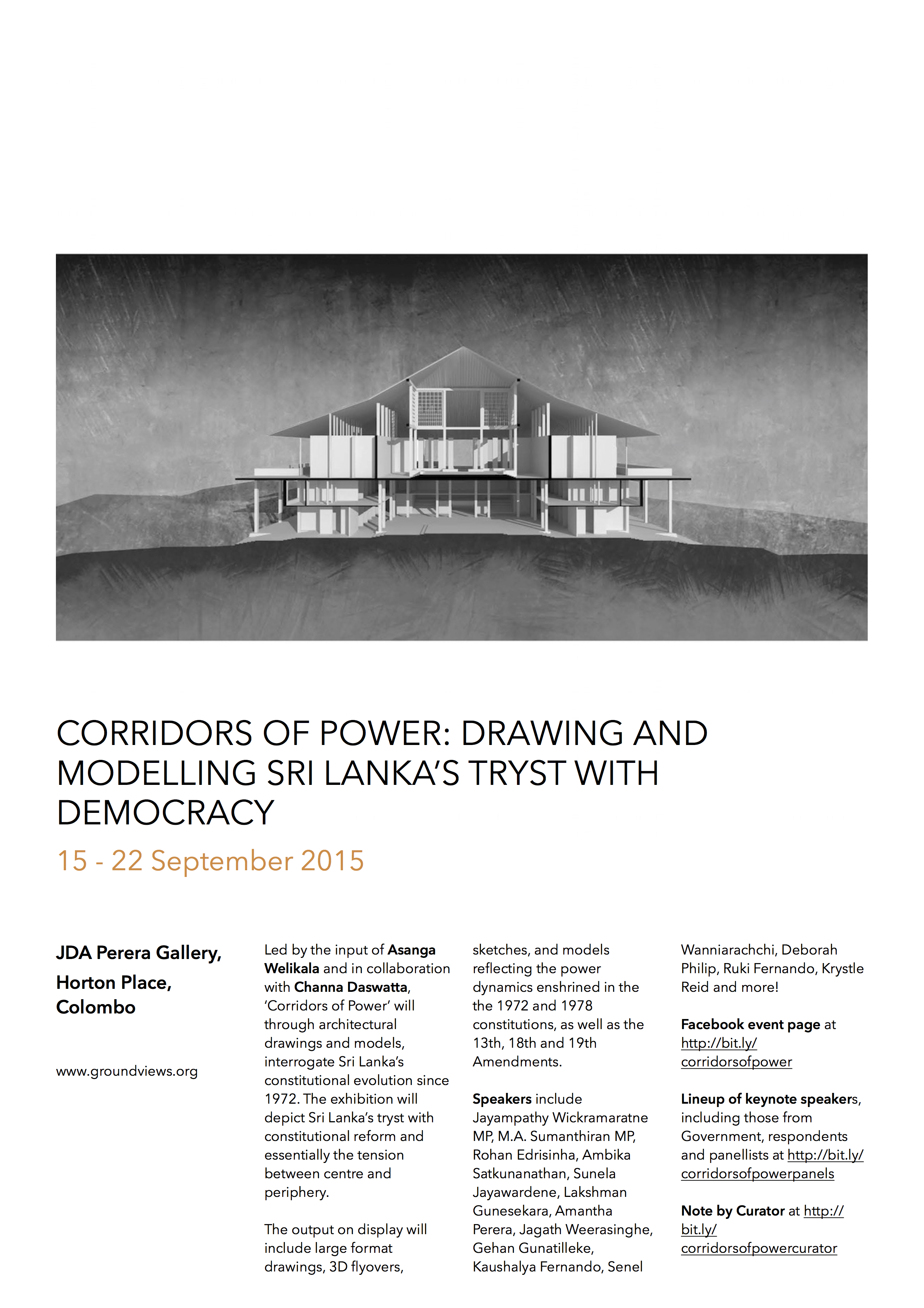

15 – 22 September 2015, JDA Perera Gallery, Horton Place, Colombo

Free and open to the public. No tickets. Limited seating at venue.

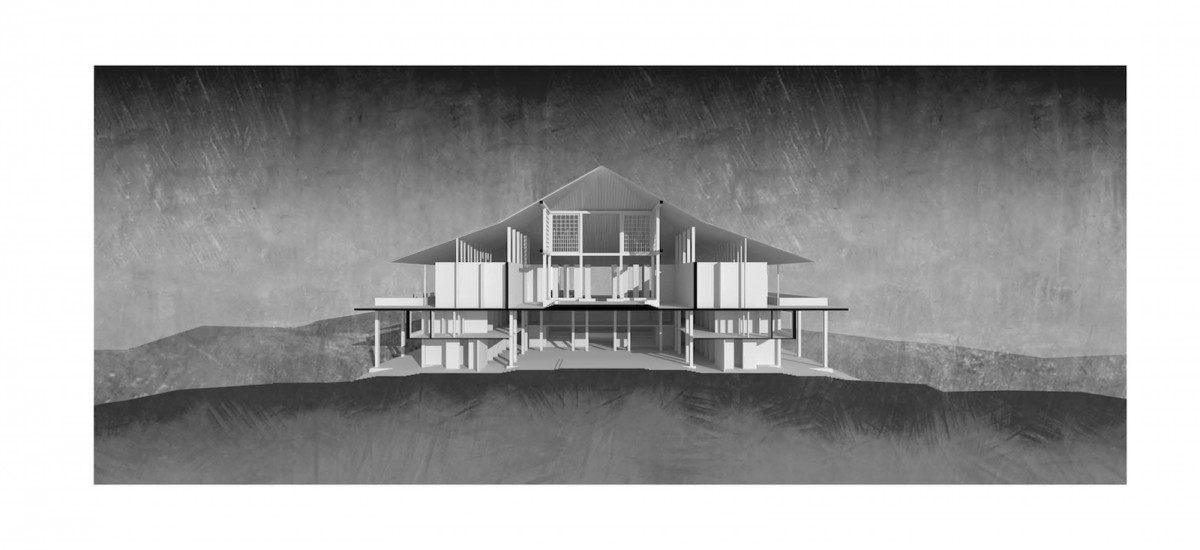

Led by the input of Asanga Welikala and in collaboration with Channa Daswatta, ‘Corridors of Power’ will through architectural drawings and models, interrogate Sri Lanka’s constitutional evolution since 1972. The exhibition will depict Sri Lanka’s tryst with constitutional reform and essentially the tension between centre and periphery.

The output on display will include large format drawings, 3D flyovers, sketches, and models reflecting the power dynamics enshrined in the the 1972 and 1978 constitutions, as well as the 13th, 18th and 19th Amendments.

Speakers include Jayampathy Wickramaratne MP, M.A. Sumanthiran MP, Rohan Edrisinha, Ambika Satkunanathan, Sunela Jayawardene, Lakshman Gunesekara, Amantha Perera, Jagath Weerasinghe, Gehan Gunatilleke, Kaushalya Fernando, Senel Wanniarachchi, Deborah Philip, Ruki Fernando, Krystle Reid and more!

Panels and keynotes

All panels, keynotes and discussions will run from 5.30 – 7pm. The opening night reception will be from 6pm to 9pm.

15th September, Opening night

- Sanjana Hattotuwa, Introduction to exhibition and curation

- Channa Daswatta, The centre cannot hold: Centripetal evolution, centrifugal desires

- Asanga Welikala, The cartography of change: Constitutional reform and the imagination

16th September, The constitutional vision of the new government (Keynote)

As reported in the media in May this year, Jayampathy Wickramaratne, the leader of a three-member team that prepared the 19th Amendment, called for a new Constitution which will include a fresh Bill of Rights and address the issues of devolution of powers to provincial councils and power sharing at the Centre. After the General Election on 17th August, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe was reported in the media expressing hope that a political consensus could be reached within months on a new Constitution for Sri Lanka, because in his opinion the issues that needed to be resolved were fairly narrow. This triumph of hope and optimism over bitter experience may not last long, and the window for substantive changes in Sri Lanka’s constitutional fabric is small. If our present constitution is fundamentally unsound, what can be done in imagining a new one to ensure the flaws are addressed? And if in addressing these flaws, hard choices have to be made, how can a constitutional reform process secure the requisite political will, above purely parochial and expedient considerations, to stay the course? How will citizens be a part of this process – as mere onlookers, or as active participants? What are the core values the government will anchor the new constitution to and seek through its passage, the entrenchment of in the popular imagination? Ultimately, independent of the success or failure of the project around a new constitution, what does the new government aim to achieve around constitutional reform in a manner qualitatively different to attempts in the past?

- Jayampathy Wickramaratne MP

- Respondent: Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu

17th September, The challenge of constitutional reform: Mediating change and managing continuity (Keynote)

The process of constitutional reform in Sri Lanka, if only just the 18th and 19th Amendments are taken into account, is deeply problematic. The opposition to the 18th Amendment, in terms of substance as well as the way in which it was pushed through the legislature, was in comparison to the 19th Amendment far more pronounced and widespread. And yet, even with the 19th Amendment, significant concerns around the lack of information in the public domain around the draft bill, the resulting lack of strategic, planned, public consultation or debate and the perplexing inability (or unwillingness) to translate into Tamil and Sinhala in a timely manner the substance of the Amendment is indicative of enduring challenges. Negotiations over substantive and core issues aside, the failure to architect a robust process of constitutional reform seriously risks the needless strengthening of spoilers, and the eventual derailment of the best intentions. How can one manage to secure public trust in a constitutional reform process? What can be done to encourage public interest in issues and considerations that so many see as largely peripheral to more existential concerns? How does a reform process deal with the legacy of the present constitution, and the common law jurisprudence that pre-dates it with the need to reimagine the State, nationhood and citizenship? What is the role of compromise, and at which point does necessary compromise turn into expedient connivance? How can vital substantive issues around the reform process, even if they don’t find direct expression in a new constitution, be publicly discussed, also leveraging the raft of technology tools available today?

- Rohan Edrisinha

- Respondent: Ambika Satkunanathan

18th September, The chiaroscuro of power: Architecture’s role in hegemony and change (Keynote)

Channa’s note on this exhibition avers thst “the premise has been that architecture is essentially about creating relationships between various spaces occupied by people and thus making the potential for interaction between them.” When the Design Museum in London named world renowned Hahid’s Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku, Azerbaijan, the winner of the Design of the Year award in 2014, critics noted that Hahid’s lack of concern over who commissioned the edifice, and who it commemorates, was deplorable. As Russell Curtis, a founding director of London-based architects RCKa, an award-winning design practice noted at the time and in response to the award, “It’s naive to believe that architecture and politics are mutually exclusive: the two are inextricably linked.” What is an architect’s role, if any, in critiquing the status quo? Is there a greater social or civic responsibility around public projects, for example those commissioned by the State, or does the client, which could be an authoritarian government, to the exclusion of all other voices, determine the final structure and order of things? What are instances where architecture, through design or appropriation and in terms of the geo-spatial organisation of space, has fuelled reform and even revolt? And if that is possible, is the converse also true – can architecture create more harmonious social relations through spatial relationships?

- Channa Daswatta

- Respondent: Sunela Jayawardene

19th September, The ‘F’ word and the Tamil National Question (Keynote)

In Sri Lanka, merely acknowledging federalism’s role and relevance in constitutional reform risks derailing the process comprehensively. The popular imagination in the South invests in the term an almost unshakeable fear of eventual secession. Years of vilification, negative stereotyping and misinformation have been – at least for those vehemently opposed federalism– successful. Opposition to the idea, and indeed, a clear understanding of its central place in architecting a new constitution, remain, respectively, high and low. On the other hand, much of this opposition stems from the enduring inability of some of federalism’s greatest champions to clearly address some of these fears, and communicate clearly what it is, and is not. Lawyers often assume society writ large to have as good a knowledge of the law as they do, and politicians often support or decry federalism based purely on parochial, electoral gain. Principled, reasoned arguments around federalism, embracing for example concepts that call for the recognition of multiple nations within a united Sri Lanka, are central to meaningful answers around the Tamil national question. And if the Tamil national question is seen as central to realising the democratic potential of Sri Lanka post-war, federalism and its discontent needs to be tackled head on. How can this be done? Given an electorate in the South largely unable and unwilling to support federalism prima facie, what can politicians do to strengthen critical reflection and support? Why is it even necessary, if as some would argue, existing provisions in the constitution are entirely adequate? Can there be meaningful debates around the Tamil national question without resorting to federalism and its promise? If maximalist demands continue without any compromise, and reciprocally, majoritarian fears around secession continue to hold hostage meaningful debates around a new constitutional framework, what is the fate of federalism in Sri Lanka and indeed, if it fails, the prospects around addressing the Tamil national question meaningfully?

- A. Sumanthiran MP

- Respondent: Ameer M Faaiz

20th September, Framing discourse: Media, Power and Democracy (Panel)

The architecture of the mainstream media, and increasingly, social media (even though distinct divisions between the two are increasingly blurred) to varying degrees reflects or contests the timbre of governance and the nature of government. How can and should media reflect on its complicity in or contestation of cycles of violence? How can ‘acts of journalism’ by citizens revitalise democracy and how can journalism itself be revived to engage more fully with its central role as watchdog? In a global contest around editorial independence stymied by economic interests within media institutions, how can Sri Lanka’s media best ensure it attracts, trains and importantly, retains a calibre of journalists who are able to take on the excesses of power, including the silencing of inconvenient truths by large corporations? Simply put, what is the role of media in securing democracy against its enemies, within the media itself and beyond?

Moderator: Asoka Obeyesekere

21st September, Drawing power: Framing the inconvenient, imagining the impossible (Panel)

Framing violence, and drawing an audience’s attention to it, can be powerfully achieved through the arts. In this reading, art inhabits a space under constant risk of expiration or asphyxiation – licenses can be revoked, scripts can be censored, art can be banned and artists can be silenced. On the other hand, art is also resistance – a space for contestation. If the pervasive architecture of authoritarianism is invisible to most, and society’s capture is through the power of deceit, art serves to decry, dissent and deconstruct. The most critical art risks pushback, whereas art that offers the illusion of critique often flourishes the most. As panellist Gehan Gunatilleke avers in his review of a very popular English play during the Rajapaksa regime, art can by design or inadvertently help strengthen the status quo: “Pusswedilla is damaging our political culture… Instead of compelling audiences to question the absurdity of their reality, Pusswedilla encourages them to accept the current political dispensation as the best on offer. This is dangerous because there can be no change without discomfort. Pusswedilla is… cleverly packaged propaganda.” How can art frame the violent without giving rise to more violence? How can, in a context of hopelessness, art contribute to a triumph of optimism in the capacity for change, over bitter experience? In critiquing loci of power, do artists lose their agency or independence by accepting funding from various interest groups, who hold and seek to expand their own power? Or is the choice contextual? How does one cultivate the imagination within repressive terrains, and frame the necessary, even when violence reigns? How can critical art’s power be strengthened, its appeal expanded, its production strengthened?

Moderator Gihan Karunaratne

22nd September, Designing the future: Plotting change, planning reform (Panel)

If architecture is a vector to interrogate the past, present and future, how can we architect (pun intended) a more just, equitable and democracy future? At its simplest, can the design of public spaces militate against social exclusion and resulting frustration spilling over into violence? Conceptually, what can be done to fully grasp Sri Lanka’s democratic potential post-war? To what extent can our future be engineered, and to what degree can this political, cultural, economic and social engineering accommodate multiple narratives, identities and competing ideas? Youth are often said to be the architects of a better tomorrow – but what role do they have in shaping the present? How should we look at the past, and yet not be held hostage by it? How can we imagine the future, not forgetting what we have been and done in the past? The avowed mission of the world renowned magazine The Economist, as noted in its pages, is to “take part in a severe contest between intelligence, which presses forward, and an unworthy, timid ignorance obstructing our progress.” How can this idea take root and find expression in our public life?

Moderator Amjad Mohamed-Saleem