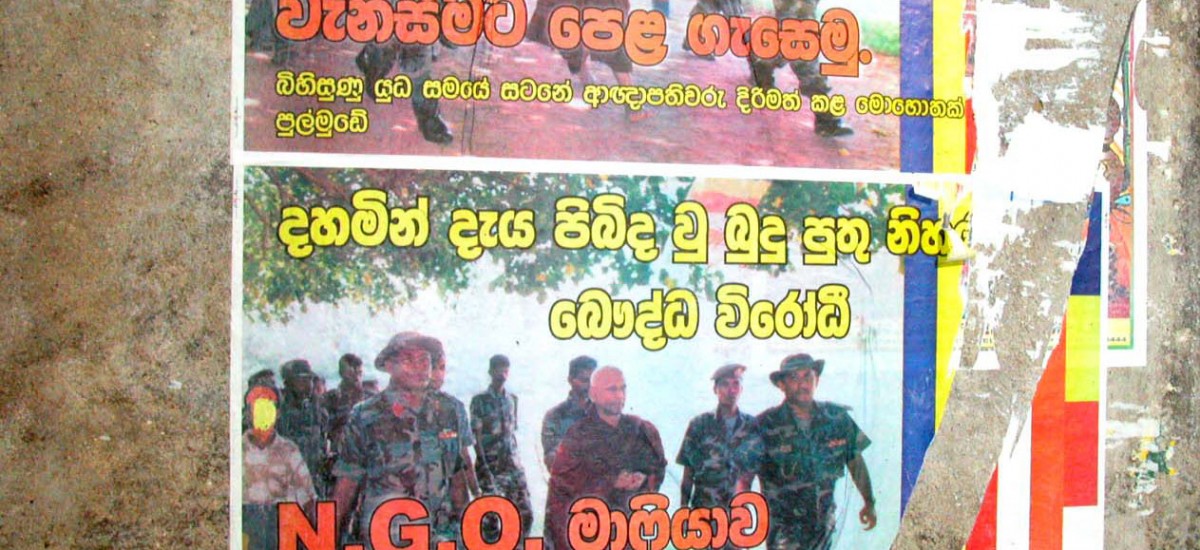

Photo courtesy JDS

Just as a criticism of the Ministry of Sports or the Cricket Control Board, are in no way a critique of Sri Lanka’s cricket team or its sportsmen and women, I must clarify that my critique of the Defense bureaucracy is in no way a critique of the Sri Lankan armed forces.

The low growl of the Defense bureaucracy in the direction of the NGOs is a dangerous portent. A growl could be followed by snarl and then a bite. What applies to the NGOs could then be tried out on other autonomous civic institutions and associations, which would include the mass media, trade unions, students unions, teachers unions etc.

What is at issue here is nothing less than the character of our society and state. Is our society one in which freedom of voluntary association, expression and activity prevails so long as these do not violate existing laws, starting with the Constitution? Or is it a society in which activity is permitted within rules and regulations as interpreted by the security bureaucracy? What is the role of the state? Is it to guarantee and defend existing freedoms and expand the realm of those freedoms or is it to circumscribe the freedoms we are accustomed to enjoy? If the former, the state is a democracy without qualifications; if the latter it is a quasi-authoritarian democracy.

One may readily anticipate the counterargument of the state’s security managers, namely that the West uses a playbook in which civil society is used for the undermining of security and sovereignty. While this has a large measure of truth, it is the case that the existence of a liberal democracy rather than an illiberal one gives the state a legitimacy and a profile that makes it far easier to defend against Western de-stabilization which uses the lack of freedom precisely as a weapon of critique and a justification for sanctions if not worse. It is far more difficult to defend from outside intrusion, a state that has delegitimized itself by reducing the area of social freedoms.

Much more than anything President Rajapaksa has done, it is the doctrine, discourse, actions and inactions, of the current defense officialdom, that have changed Sri Lanka’s target profile from May 2009 when the country had an effective diplomatic shield. It is the hardline defense bureaucracy and the even more hardline Sinhala Buddhist lobbies such as the BBS and its allies that have made Sri Lanka less, not more defensible from its powerful global critics and foes.

Which poses a worse danger to the image and interests of the Sri Lankan state, of Sri Lanka as a country and indeed of the Sinhala majority: the unchecked BBS, Sinhala Ravaya et al, or the unchecked NGO community?

The more legitimate a state is perceived as in the world system, the more difficult it is for external actors to target it. The less legitimate it is perceived to be, the easier it is to target it. Panama’s Noriega, Iraq’s Saddam and Libya’s Gaddafi are just a few examples

The freer and democratic a state is, the more legitimate it is perceived to be and therefore the more difficult it is to target it. A free society and a democratic state are a hard target, not a soft one.

A free society and democratic state possess far greater ‘soft power’ than an illiberal or authoritarian democracy. The greater the ‘soft power’, the greater the total national power of the state, the harder the target; the lesser the soft power, the softer the target.

It is far easier to defend the sovereignty of a manifestly or demonstrably free and democratic state in which institutions function impartially and independently, than it is to defend the sovereignty of a less than free and democratic state.

I must confess a weakness. My late friend Dr. Newton Gunasinghe, one of Sri Lanka’s most brilliant and literate Marxists minds (second only to the great GVS de Silva), used to say when I was a founder member of the Social Scientists Association (in my late teens) that my one methodological weakness was that I “always assume rationality”. That weakness probably abides. Irrationality in public policy, especially in matters of the national and state interest, troubles me. When a state acts irrationally in the strategic realm, and does so continuously, with sporadic intervals of lucidity, it worries me.

Any regime that could, in the wake of the international outcry over Aluthgama and its aftermath and while a UN International inquiry is about to commence sittings, snap at the ankles of the local NGO community and thereby give the world’s sole superpower another criticism to level against the Sri Lankan state, is acting more than a little weird. There is something wrong with its wiring. But then again it had to have been faulty wiring that sent heavily armed soldiers in battle-gear into Rathupaswela while the country was under international scrutiny.

The ominous growl of the defense bureaucracy with regard to the NGOs raises the inescapable question: if things are heading this way now, before the elections, what will the situation of autonomous civic associations and dissenting civil society in general be, on the morning after the parliamentary elections and when the government has won handsomely, as it will if the darling of Colombo’s cosmopolitan civil society, Ranil Wickremesinghe, is the opponent and alternative?

The only way to save civil society from being ground under by the state security apparatus which will put in place an undeclared ‘state of siege’ as the international inquiry gathers momentum, is if the parliamentary balance changes at the election. A new ratio in parliament and a new governing coalition can appoint a deputy minister of defense who will be responsible to the legislature. In any case, the legislature’s control of the purse-strings can hamstring the authoritarian apparatuses.

A new balance in parliament is however, contingent upon a strong showing at the presidential race. If the opposition’s showing is weak, the president’s victory by a large margin will have a domino effect on the election to the legislature.

Chronic counterproductive irrationality is not the preserve of the state’s security managers. Surely there is a clear logical contradiction between the interests—including the existential interests of survival—of dissenting civil society and its socio-political or politico-ideological preference for the UNP’s existing leadership which cannot slough off the opprobrium of un-patriotism and/or come within light years of the audio-visual advantage, public communication talents and social semiotic skills of President Rajapaksa?