Submitted to Groundviews as a response to Kalana Senaratne’s assertion that Buddhism does not have a means for contemporary political engagement, in The ‘Mad Monk’ Phenomenon: BBS as the underside of Sinhala-Buddhism.

###

Being Sinhala to the village folklorist Farmer Mudiyanse Tennekoon was not a matter of religion or ethnicity, it was the practise of an elevated or exalted (arya) way of living: if you live in dhamma, dhamma will protect you. A nation of sunworshippers from a time before time, this general or common consensus (Mahasamatta) formed the bedrock of the incorporation of Buddhist precepts into arya Sinhala.

Joseph Campbell described four key functions of mythology: metaphysical, cosmological, sociological and pedagogical. The metaphysical function evokes a sense of awe at the mystery of existence. The cosmological function presents an image of the cosmos that maintains and elicits this experience of awe. The sociological function is to validate and maintain a sociological system with a shared sense of right and wrong. The pedagogical function of myth must provide the psychological support of the individual through the various stages of his life and to do so in accordance with the social order, the cosmos and the mystery of his group.

The institution of Mahasamatta represented the recognition of the supremacy of the unseen god, King Mahasamatta, who oversaw the sharing of grain in exchange for a portion. The King set the standard for the nation and as the King was not seen it was the rightness of his rule that proclaimed his adhesion to the ten royal virtues, the Dasa Raja dhamma:

- Aviroda: Non-revengefulness

- Khamthi: Patience

- Avhimsa: Non-violence

- Akkodha: Non-hate

- Tapa: Restraint

- Maddava: Courtesey

- Ajjava: Integrity

- Pariccaga: Recognition of talent

- Sila: Morality

- Sharing:Dana

The Four Noble Truths and the Eight Fold Path are the means for the ultimate comprehension of the mystery through the individual cultivation of unbounded loving kindness. Arya Sinhala is essentially meticulously living the five assertions (from Pancha Sila by Asoka Devendra):

- I assure all Beings that, their lives are safe in my presence.

- I assure all Beings that, their possessions will be safe in my presence.

- I assure all Beings that, their moral goodness will not be violated by me.

- I assure all Beings that, their confidence in me will not be betrayed.

- I assure all Beings that, I will not abuse my own moral goodness.

While the individual is seen as secondary to the community the nature of a consensus requires cooperation not coercion. Accordingly this understanding of what dhamma is to the individual is of paramount importance to the community as a whole. Isaline B. Horner in the essay Dhamma in Early Buddhism:

“Primarily dhamma means the natural state or condition of beings and things, the law of their being, what it is right for them to be, the very stuff of their being, evamdhammo. If they are what it is right for them to be, if they are right without being righteous, they are true to themselves. So dhamma also means truth, with the derived meaning of ‘religious’ truth, hence the Buddhist doctrine, dhamma or saddhamma, the very or true teaching, our own teaching. If things and beings are true to themselves they will know how to act, or should know how to act, although dhamma may still have to be pointed out to them…

“Truthfinders not only gain a full comprehension and knowledge of dhamma, but in virtue of this they become dhamma: ‘dhamma-become’, Brahma-become, these are synonyms for a Truthfinder’… it is not peculiar to Buddhism, that when, and only when, you completely comprehend, then you become that which you comprehend…

“So, if you fully know dhamma you become it, and if you fully know truth you become it. Hence Gotama is not only spoken of as dhamma-become (dhammabhūta); he has as one of his epithets, ‘He whose name is Truth’, Saccanāma.”

From the same collection of essays edited by Ranjit Fernando, Frithjof Schuon specifies the perennial solution:

“To discern the Real, to concentrate on it, or more precisely, on so much of it as is accessible to us; then to conform morally to its nature; such is the Way, the only one there is.”

(from The Unanimous Tradition, Ranjit Fernando Ed., Sri Lanka Institute of Traditional Studies, Colombo, 2nd Edition, 1999.)

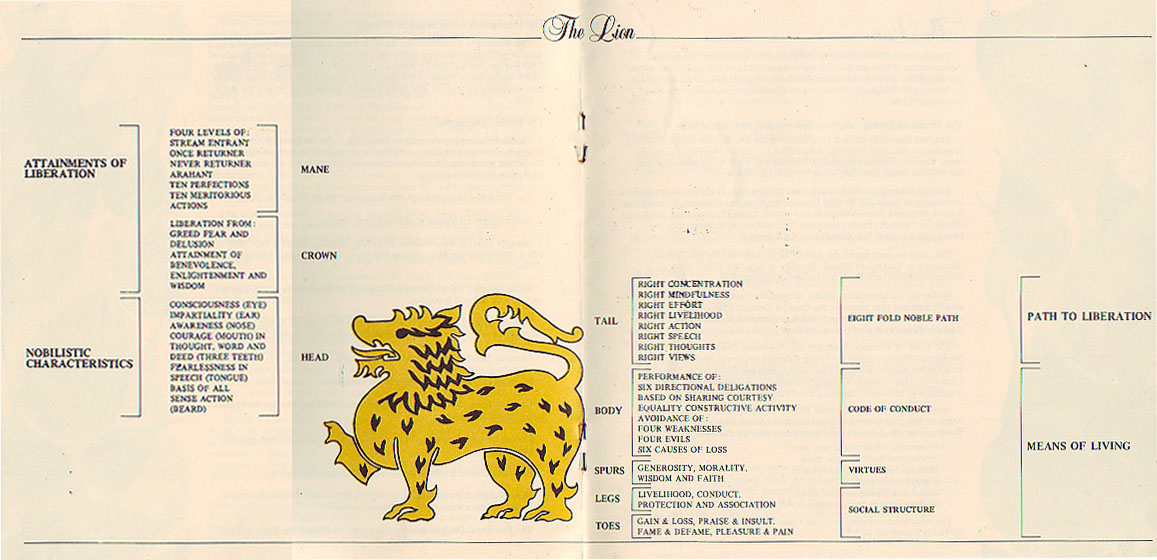

The Lion flag symbolises this understanding:

(From The Lion Flag by C. Upali Senanayake. Click here for larger image.)

Farmer Mudiyanse Tennekoon accordingly could not agree with Kalana Senaratne’s statement:

“…the inadequacy of the true Buddha-teaching for contemporary political engagement, especially in an identity-seeking, identity-promoting multi-ethnic and pluri-national political setting. In other words, the teachings of the Buddha woefully lack those elements with which you can zealously promote, protect, construct your own identities, your own political interests and prejudices, or engage in contesting those promoted by other ethnic and religious groups (more so, in the contemporary state-centric geopolitical framework).”

Arya Sinhala necessitates constant mindful awareness and if practised properly increases sensitivity and discernment. The restoration of the common wealth of Lanka required no less than a return to the Village council and the rule of Mahasamatta. Only if the rights of the peasantry to live a traditional life was honoured could any semblance of democracy return to Sri Lanka. It would be honoured when all living things were protected from the depradations of man. When our clean waters ran free nourishing the land and all that lived in it. When the people had leisure to pursue their interests, Tennekoon often said, “Everyone must dream their dream.”

A pamphlet Tennekoon co-authored with a retired civil servant Mr. Luckuruppu titled, Universal Welfare Organisation, (UWO) describes the four types of villages in Sri Lanka prior to 1833:

- The Gabadagam (or royal villages) owned by the King and benefiting both the inhabitants and the rulers by way of mutual obligations. These provided the revenues for the good governance of the country;

- The Nindagam (or villages) entrusted to the chiefs and officials for the common sustenance of themselves and the resident people. Mutual obligations enabled the social hierarchy to co-exist peacefully;

- The Viharagam (or temple villages) which were administered by the lay officials for the maintenance of buddhist institutions, monasteries and places of worship, to provide a blessing to the people;

- The Devalegam (or villages) dedicated to various local deities, and administered by lay officials for the maintenance of rituals and ceremonies which formed an integral part of the traditional culture, its arts and crafts.

Village elders constituted an ad hoc village council or Gansabha that conducted the affairs of each village. These were essentially the fulfillment of their individual obligations called Rajakariya, nominally service to the King, but in reality community service on behalf of the village. The gansabha also formulated the village Cultivation Plan and the regulation of irrigation water. The gansabha adjudicated disputes and dispensed justice and was entrusted with the conservation and maintenance of all natural resources. A network of village councils were grouped together as korales or divisions, next in to districts or disavas and finally a rajaya a kingdom or commonwealth with community ownership of land and natural resources.

“…The legal administrative and social reforms initiated by the Colebrook-Cameron Commission in 1833 set in motion the disappearance of the traditional social system that had prevailed from the 3rd Century B.C.E… The Colebrook Reforms opened the way for the expansion of the colonial plantation economy with resultant wholesale degradation and destruction… of the forests, waterbodies and waterways, soils, flora, fauna and humanity nurtured by 2500 years of Buddhist civilization…” – Tennekoon, UWO.

Tennekoon said that the restoration of the Commons of Lanka required direct political involvement by the universal adoption of Mahasamatta. Each individual must recognise Mahasamatta as the only legitimate ruler of Lanka. The key was not to consider the objective but simply to live it. He believed that once a majority of Sri Lankans began practising it, a tipping point would be reached and it would again become distasteful (appirri) to act outside it. We must restore the inherent sustainability of the puranagama system of life with the application of appropriate modern technology. It was crucial that such technology was from the public domain and capable of being built locally.

As I said above, Tennekoon believed that everyone had a dream, and his was the resurrection of Dharmadvipa, the adhesion to arya Sinhala in a modern idiom, and saw among the first steps in this direction the adoption of the principles of ahimsa by society at large. He especially felt that it was wrong to kill cattle but allowed that one could follow the Kataragama tradition and eat fish or fowl.

Tennekoon’s revolution is a passive one, its weapons are the banishment of ignorance and an aspiration to arya Sinhala. Despite colonial attempts to systematically destroy the arya way of Sinhala some semblance of it yet remains. There is still something worth saving. He dismissed as profane what he called the Galle Road culture and its post-colonial dystopia. His reality was a different one: “There is a way to behave and we learn it at the feet of our Mother.”