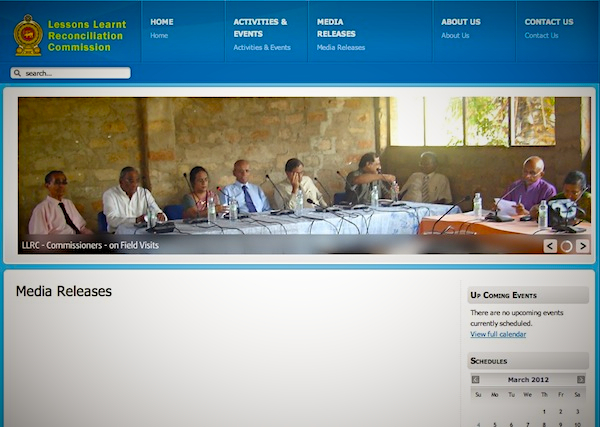

The official media page of the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) tells its own story. It’s blank. There’s literally nothing on the official website of the LLRC that provides information on public statements by the LLRC and coverage of its proceedings in the media. Furthermore, it’s impossible to find the interim recommendations or the final report of the LLRC on the official website.

The interim recommendations of the LLRC were first published in full on Groundviews. The most comprehensive record of media coverage on the LLRC, from domestic and international media, is also on Groundviews. Long before the LLRC’s official website was launched, Groundviews collated and published official submissions to the LLRC. With 214 submissions, it’s far more comprehensive than the records currently on the official LLRC site (the LLRC site does have a record of field visits – more on this partial set of records later). Groundviews served as a platform to correct mainstream media misreporting and misrepresentations of key submissions, and translated into English disturbing official testimony and Tamil media coverage of the proceedings, which were, at best, under-reported in the English and Sinhala mainstream press.

When the LLRC’s Final Report was made publicly available, it was placed on a decrepit government server that promptly crashed due to the high volume of traffic. We managed to download a copy, mirror it, and publish it. Today, the report and annexes can be downloaded, in theory, from the website of the Policy Research & Information Unit of the Presidential Secretariat of Sri Lanka. However, given that the site is so unreliable and slow, we again spent some time downloading all the annexes and mirroring them for easier access, linking and embedding on other sites. This isn’t rocket science, and as noted before, they are impossible to find on the LLRC’s official website.

Even though most, if not all of the LLRC’s public sittings and submissions were recorded, not a single recording is available on the LLRC’s official website. Again, this content is available on a website created and curated by the International Centre for Ethnic Studies (ICES), along with other content around the LLRC.

The LLRC’s Final Report was released to the public in December 2011. Today, the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) released a Sinhala translation of Chapter 9 of the report, which reiterates points made earlier in the report and has some interesting recommendations. Up until the public release of this unofficial translation, the government has not released to the public domain a translation of the report in Tamil or Sinhala. Bizarelly, Azzam Ameen, a Sri Lankan journalist on 1st March publicly tweeted that the President’s office has official translations of the report in all three languages, which if true, begs the question as to why a more public release of the report in Sinhala and Tamil hasn’t occurred and isn’t encouraged.

At around the time the LLRC was constituted and began its work, Chandra Jayaratna (former President of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce and LMD Sri Lankan of the year 2001) wrote to the commission and to Groundviews on how Information and Communications Technologies could help the LLRC’s proceedings, and reconciliation writ large in Sri Lanka. His submission fell on deaf ears.

Warts and all, the LLRC was a process that generated a lot of public debate, both within and outside the country. It elicited revealing submissions, including from women and men in the Vanni and Jaffna. From the get-go, it was voices from civil society, not government, who called upon the LLRC to leverage modern technology to ensure that the information it received wasn’t lost. Sadly, much of it is already lost. There’s no record of what happened to the official audio recordings. Hundreds of written submissions by those in the Vanni and Jaffna in particular, in Tamil, aren’t available online or on the official website of the LLRC. What’s featured on the LLRC’s website under field visits is really a sub-set of a much larger corpus of submissions. Whether or not they fed into the LLRC’s Final Report, they are an invaluable record of Sri Lanka’s history, expressed through the public. There is no record of these submissions in the National Archives. These are vital records for posterity, but quite possibly already irrevocably lost.

What remains of the LLRC’s proceedings and output – its interim report and recommendations, the accessibility and translations of its Final Report, most of the public submissions in Tamil, Sinhala and English, audio recordings and detailed records of media reports – are all, without exception, carefully curated and published online for public access by the very NGOs and platforms, including this site, that have been openly and repeatedly vilified by those in and partial to government. And all the government itself has managed to do was to establish a website for the LLRC – that too rather late into the LLRC’s activities and bereft of vital records.

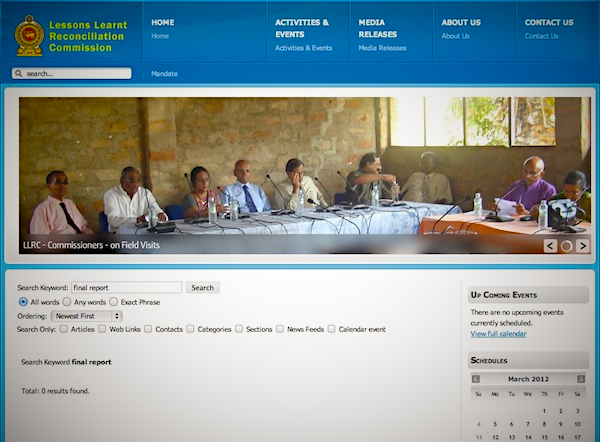

Since the LLRC was constituted and ended its mandate, there’s been more public debate and discussion around reconciliation Groundviews and Vikalpa alone than on any official mechanism or online platform established around the Panel’s proceedings or to examine its findings. Search for the LLRC’s final report on its official website. The search result (0 results found) is a prescient indicator of the government’s ability and willingness to pursue and implement the panel’s recommendations. And all the while, they will continue to employ a language of vicious hate and harm against civil society actors, who have in fact done more to support the LLRC’s proceedings and output.

Post-war Sri Lanka in a nutshell.