Updated 2.15pm, 30th November with added analysis of tags

“The first is that, in Sri Lanka, it would never be possible for any one to play “Julian Assange” and dare face an open media briefing in Colombo, to justify his or her claims on war crimes and torture. Right or wrong, excessive or not, that “democracy” is nowhere within the shores of Sri Lanka and would not be, for many decades to come. There is also no possibility of any lawyer, any public litigant, requesting Courts to “order” relevant authorities to begin investigations into allegations of crimes committed during war, as in Britain. Relevance if any on such democratic practices, is almost naught.” – From WikiLeaks to WikiLanka: War Is Definitely Savage Though “Accusations” Differ, Kusal Perera

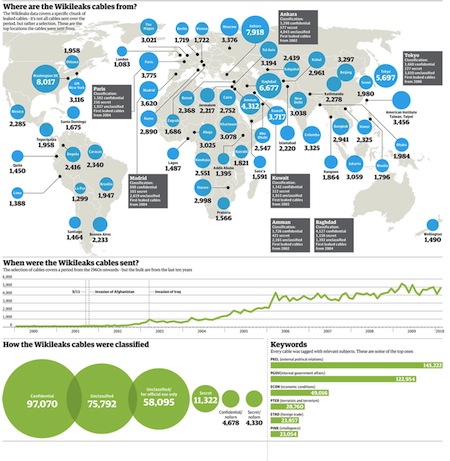

The unprecedented release of US diplomatic cables (i.e. confidential briefings) by Wikileaks is, at the time of writing this, only just making it to global news media. Called Cablegate by Wikileaks (which was subject to a massive denial of service attack earlier in the day, but is now back online), it is quite simply the world’s largest classified information release, breaking a record Wikileaks itself had set earlier with the release of documents pertaining to the Iraq war earlier in 2010. As noted on Wikileaks,

“The cables, which date from 1966 up until the end of February this year, contain confidential communications between 274 embassies in countries throughout the world and the State Department in Washington DC. 15,652 of the cables are classified Secret… The cables show the extent of US spying on its allies and the UN; turning a blind eye to corruption and human rights abuse in “client states”; backroom deals with supposedly neutral countries; lobbying for US corporations; and the measures US diplomats take to advance those who have access to them.”

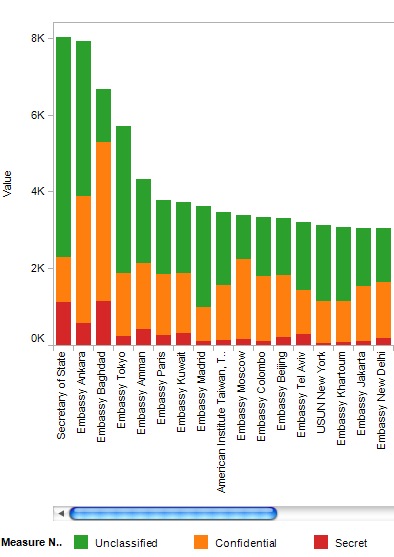

What is interesting for us is that material about Sri Lanka, and from the US Embassy in Colombo, constitutes a significant section of the dataset. This includes thousands of cables classified Confidential, hundreds classified Secret and many more that are unclassified, but not obviously meant for public consumption.

Image courtesy Wikileaks, Cables by Origin

Contained in the dataset are 3,325 of cables from the US Embassy in Colombo, from 1986 to 2010. There is one cable on 19 May 2009 (the end of the war) and 4 on 26 January 2010 (the day of the presidential election in Sri Lanka). The last 3 cables are from 26 February 2010.

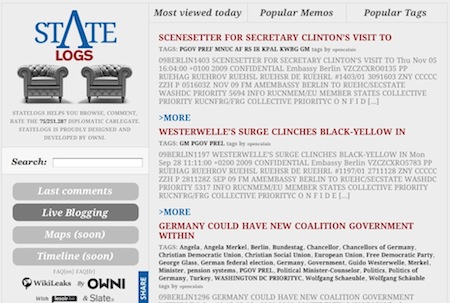

This visualisation / infographic by The Guardian gives an idea about how large the dataset is.

High resolution version here.

Meta descriptions and associated tags of all the cables from the US Embassy in Colombo can be accessed here. Groundviews has also compiled this list as an Excel spreadsheet. The full body text of the cables is part of the original data file that no one save the likes of the New York Times in the US, The Guardian in the United Kingdom and Der Spiegel in Germany have had access to at the moment. Wikileaks itself says that,

“The embassy cables will be released in stages over the next few months. The subject matter of these cables is of such importance, and the geographical spread so broad, that to do otherwise would not do this material justice.”

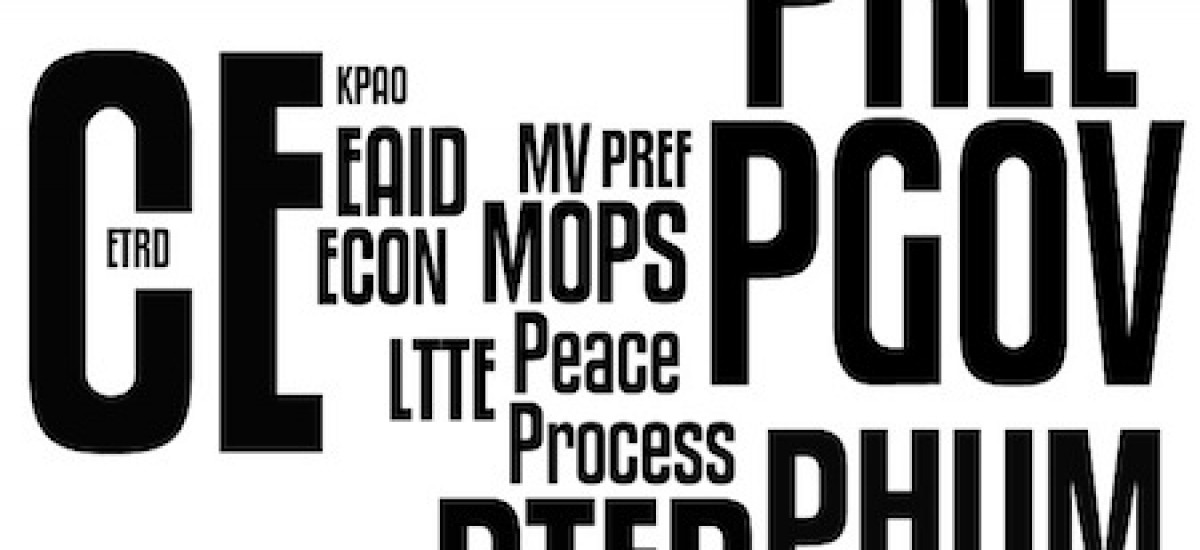

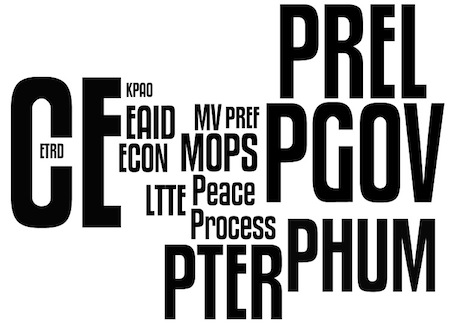

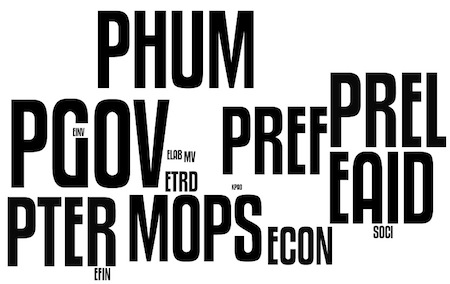

Groundviews visualised the classification tags of all the 3,325 cables since 1986.

CE stands for Sri Lanka. Cables on PREL (External Political Relations), PGOV (Internal Government Affairs), PTER (Terrorists and Terrorism) and PHUM (Human Rights) feature heavily, with ECON (Economic Conditions) also significant. Cables tagged with LTTE and Peace Process, unsurprisingly, also feature heavily.

However, from 1 January 2010 to the date of the last cables in late February, neither the tag LTTE nor peace process make a significant appearance. Revealingly, what the US is more concerned about during this time – which also saw the presidential election, the re-election of Mahinda Rajapaksa and in early February, the arrest of Sarath Fonseka – is human rights, internal government affairs and external political relations. Given that the war is now long over, it is also interesting that a significant tag in these cables is MOPS, military operations. One assumes these cables deal with military operations from the previous year(s). There is also a significant increase in the mention of EAID, or Foreign Economic Assistance, which when read together with the other key tags, suggests contextualisation of aid within analyses of internal government affairs and its military operations of yesteryear.

A full glossary of the tags can be accessed here.

Through Google, one can see an overview of the frequency of the cables over 2009 – 2010.

But it is not just through the US Embassy in Colombo that Sri Lanka falls into the spotlight in Cablegate. As reported in The Guardian, the US state department asked US diplomats around the world and at UN heaquarters to provide detailed technical information, including passwords and personal encryption keys for communications networks used by UN officials. This included,

“Views and intentions of UNSC, UN human rights entities, and members regarding Sri Lankan government policies on human rights and humanitarian assistance; UN views about appointing a Special Envoy for Sri Lanka.”

Clearly then, the US is very interested in war crimes in Sri Lanka. But what does this mean for human rights defenders and activists in Sri Lanka, particularly those who may have confidentially, or in fora under the Chatham House rule, divulged information reflected in these cables that even today, if revealed, places their lives at great risk?

The New York Times, in what it already has and will publish, first sent material to the State Department for them to react, though it did not always follow ‘recommendations’ for content to not be disclosed. Questions posed by readers to the NYT Editorial Board are essential reading in this regard. As noted in an editorial note justifying the publication of the Wikileaks cables, the New York Times avers,

“The Times has taken care to exclude, in its articles and in supplementary material, in print and online, information that would endanger confidential informants or compromise national security. The Times’s redactions were shared with other news organizations and communicated to WikiLeaks, in the hope that they would similarly edit the documents they planned to post online.”

But the point is that the dataset is even today available as a torrent file directly from Wikileaks. It is unclear to what extent Wikileaks itself has redacted information that can compromise the safety and security of individuals, and this includes human rights defenders. It is likely they have not, since it is impossible for any one organisation to make a judgement call about this kind of information without deep, localised knowledge and context. This means that over the coming weeks and months, there is a high probability that some of the cables – and these include cables from the US Embassy in Colombo – will place human rights activists, already under scrutiny and a Damoclean Sword at even greater risk.

Here again we recall Kusal’s words,

“The Obama and Cameron governments are no different to the Rajapaksa regime in denying and accusing those who throw up issues relating to war crimes and breach of international human rights law, where they conduct war. Their “national safety and security” rhetoric, politically allies with “patriotism” in Sri Lanka. They too therefore imply the “war against terrorism” they are involved in, “is a humanitarian war” in liberating the people from “terrorism” as Rajapaksa claimed his war was.”

On 22nd November 2010, Wikileaks on its Twitter feed noted, “The coming months will see a new world, where global history is redefined.” They weren’t kidding. The implications of Cablegate are global and profound. For professional journalism, as the questions to the New York Times alone suggest, it is new ground they too are struggling to define and defend. For data visualisation, the dataset offers an unprecedented array of information to make sense of, and present. OWNI’s outstanding work in particular with Cablegate stands out in this regard, and will only grow in utility and usefulness over time.

For the US in particular, that which it would have loved to keep secret is now in the open. Not all of this is progressive. Much of it will in fact be very problematic and ironically, immensely helpful for the very governments Wikileaks seeks to name and shame. It raises the question as to whether what is in the public interest in the US, and defined by say the New York Times, is in the public interest for other countries. Without editorial oversight, mature judgement, curation and contextualisation, this information can be used in any number of ways to further erode democracy and human rights. How this will play out will be interesting, but there is no closing Pandora’s box.