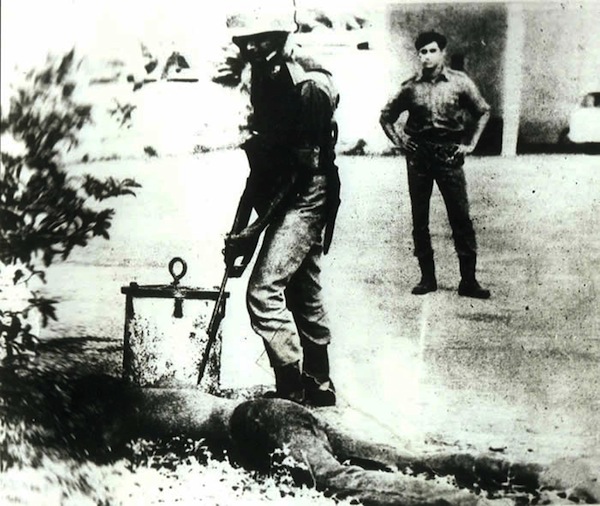

Photo courtesy Tamil Guardian

First, the colours. My memories of July are full of dark colours, foreboding and angry. Grey dominates. Grey, the colour of the smoke that is everywhere, even in your tears. Then there is red, bright and angry, the colour of blood, like a crimson spray on the grey smoke. Lastly there is the orange of the flames, fiery and frantic, lapping up the blood and the groans of collapsing masonry, before disappearing into the smoke. Dark and sharp colours that daub the memories of the horror.

Then the crowds. I remember they were mostly young men, with crowbars and clubs. Knives too there may have been but the crowbars I remember well. Crowds of young men roaming High Level Road, gathering around the shops owned by Tamils. I also remember the crowds watching, some cheering, some puzzled but none intervening. Then came the flames, roaring and raging, enveloping the two grocery stores near the Kirulapona bus stand. And as the flames rage some men are seen washing the Sinhalese owned store next door with buckets of water. Men as eager as the men with the crowbars. Through the throngs of people a man is running, his white shirt and sarong drenched in blood. And the air begins to choke with smoke.

I also remember the police jeep, an officer getting out and pointing a pistol at the crowd, trying to intimidate the young men, and the indignation of the boys at the temerity of the man. Then comes the passing army truck, full of soldiers with guns. And the soldiers scream at the police officer to back off. The officer obeys.. ‘Jayaweva!’ the crowd roars and the soldiers raise their guns in salute before the truck moves on. ‘Jayaweva!’

I also recall the body. The body of Mr. Mudiappa, a long time resident of Kirulapona. They set fire to his house and he died in the blaze, refusing to leave the house he had lived in all his life. The next day when the curfew was lifted, a man, a total stranger, took me to the burnt out house and showed me the body. We asked the fool to run he said. But he decided to die. Then he took me on a guided tour of a landscape littered with ruins. I remember the cars, burnt out, some overturned, the vehicles that belonged to either Tamils or to Sinhalese who refused to give the arsonists petrol. Here we burnt one alive the man said pointing to a car. And there two more. The bravado of a killer who had nothing to fear.

I remember the neighbours. Three of them, two men and a woman who had jumped from the rear balcony of their upstairs flat behind our house as the mob ransacked the place. They were not the most agile people but they had jumped to save their lives. And they came to our house. They never begged for refuge but they came hoping, probably because they felt we were different to the mobs that rampaged. Or they just hoped for the best.

And we gave them shelter, for several days until we found them a place in a camp. What happened to them after that we do not know. I hope they survived the war that was about to break out.

These are poignant memories. Refusing to go away. But they are not the most enduring.

When school reopened after several days my classroom was abuzz with mates chattering away about their own memories. Apart from me and one other friend no one else condemned the horror without reservation. It was horrible, yes, they agreed. But the bloody Tamils had asked for it. These were not kids who had been brought up in shanty towns from where we believed at the time most of the goons had emerged. These were kids whose parents held good jobs, lived in comfortable houses and perhaps even had Tamil friends they had been to school with. And at that age, children still learn a lot from their parents.

I also remember another friend, a good mate whose family also sheltered their Tamil neighbours. When I visited them one day while the Tamils were still in their house I found them reprimanding the people who had sought their goodwill for what the Tamils had done to bring this upon themselves. I can only imagine the humiliation of those hapless people having to take refuge in a Sinhalese household only to be told it was their people’s fault. Each time I hear a Sinhalese say the riots were only the work of a minority or ask what problems do the Tamils have, I remember this. Then I cringe.

But the most enduring memory is of my father, on that first night, as we settled down to dinner. He approached our neighbours who were still gripped with fear and invited them to dinner. My father, almost bent double, spoke in a soft, almost broken voice and asked them to eat first adding that we have not been able to prepare much due to the curfew. Anyone looking on without knowing the circumstances would have thought that my father was the victim. So humble was he.

For that night we were all humbled and broken. And we have not been made whole since.