Photo courtesy of News Tube

It should be universally acknowledged that the socioeconomic impact of the multiple crises which have been unfolding in Sri Lanka since the COVID-19 pandemic has invalidated all human development indicators measured since 2019. Many children lost their right to education with almost two years being out of school or having to resort to online classes. The economic crisis made it more difficult for families to afford education and the likelihood for children completely dropping out of school increased.

Save the Children’s Rapid Needs Assessments conducted in December 2022 stated that children who were not enrolled in education had risen by 2% (1% in June and 3% in December 2022), and discontinuation of education had risen by 5% (1% in June and 6% in December 2022). It was also found that out of children who don’t attend school every day, 32.2% were from Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi districts (significantly higher than other districts surveyed), indicating a disproportionate impact of the crises on children’s education in the North.

The study said, “There are indications of an increase in the average monthly income, but the average monthly spending grew faster, causing the majority of households to adopt coping techniques and force more members to work, prevent children from attending school, and involve children in unpaid labour. In order to meet their basic food and schooling needs, more households have adopted a moderate or high level of coping severity compared to their situation in June 2022.”

The current labour law does not allow children under the age of 15 to engage in any paid or unpaid work unless it is light agricultural work done during out of school hours. It also doesn’t allow children over the age of 15 years to engage in hazardous work. However, the studies have identified heightened risks for children to enter the labour market and to meet the economic needs of their families.

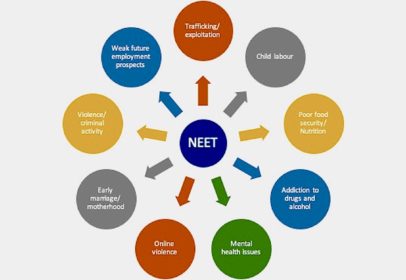

The National Child Protection Authority, in statement, said that the current socioeconomic crisis has heightened the risks for children to be used for labour. It is also important to consider the impact on children and youth who are Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET). This is particularly pertinent for the 16 to 18 year age category as there is no data to understand the incidence of hazardous labour among this age group. Research across the world finds specific threats facing children and young people who are NEET, one of which is exploitative labour.

Figure 1: Diverse impacts of not being in education, employment or training (NEET)

What are we doing as a country to tackle this problem? Child labour requires remedies. It is common for many to blame parents for taking children out of school and for making them work. But if one is unable to put food on the table (at least one meal a day), wouldn’t survival take precedence over education? Children have dropped out of school because parents aren’t able to provide three meals a day; the survival mechanism/thought process is if children stay at home and sleep, the family can manage without breakfast and if children are able to contribute even in a small way in generating income to the family, the family just might be able to survive this crisis. This is the reality of most of the households that are economically poor (41.7%), which have members who have never attended school (93.3%) and which depend on temporary income sources (58.7%).

Social protection as a remedy for children’s wellbeing

Sri Lanka’s social protection systems have failed to prevent the poor becoming poorer. The question to ask is, “What type of system might enable the most economically poor children and families to rise out of poverty and stay out of poverty?”

In the wake of IMF bailout conditions that require revenue based fiscal consolidation that is accompanied by stronger safety nets among other factors, there is a lot of buzz about social protection reforms stemming from the government as well as international organisations. This is a window of opportunity for us to get our social protection system right. Due to issues of corruption, poor governance and management of social protection schemes that have allowed nearly 50% of inclusion/exclusion errors, only 36.4% of the population are currently receiving at least one form of benefit. This is reduced to 32% in relation to children.

Social protection can be conceptualised as a set of public policies, programmes and systems that help women, men and all children to (i) reach and sustain an adequate standard of living; (ii) improve their ability to cope with risks and shocks throughout their life cycle; and (iii) claim their rights and enhance their social status.

However, the impact of an economic crisis on children will remain even if the social protection systems attempt to reach these objectives. That’s because unless the system becomes child sensitive and is geared to address specific patterns of children’s poverty, it could result in unintended negative impacts on children, and prevent the system from maximising benefits for them. Why is this so pertinent?

From this definition it can be understood that social protection systems have to support people to claim their rights. Children have been a marginalised and exploited part of society for generations owing to their inferiority in competence, development, power and social status. Hence, if a social protection system is to effectively address children’s poverty, it will have to have special affirmative measures to ensure that all children are able to equitably access services. This is the core of child sensitive social protection. It does not imply that the system should target children as the main beneficiary but instead enables children to access services such as health, education, protection and social supports as a right, together with financial assistance. Additionally, the extent to which policymakers take into account the views and voices of children and parents as part of the process acts as another key determinant to measure the effectiveness of a child sensitive social protection system.

Children and young people who are NEET as a result of the economic crisis during the past year are likely to face its impacts as depicted in Figure 1. Child labour, trafficking and exploitation associated with it is a critical implication. However, the problem can go beyond negative coping measures to face the economic crisis to broader protection and education issues for children. Children and young people who are NEET are more likely to engage in anti-social behaviour such as drug use, cybercrime and communal/gang violence. In Sri Lanka, drug use among young people has become an endemic problem with synthetic drugs such as crystal methamphetamine (ICE) being widely available and accessible.

Across the world, one of the fast emerging problems in the online space is cybercrimes perpetrated by children against children. Being NEET provides the space and opportunity for children and young people to be exposed to such harms and risky behaviour. Children who depend on the mid-day meal provided by the school would drop out if the meal is no longer provided. Although this situation arose at the beginning of the crisis, fortunately the government has resumed its school meal programme and other organisations have complemented these efforts by working in partnership with the government. One such programme is Save the Children’s Promoting Autonomy, Literacy, and Attentiveness through Market Alliances (PALAM/A) project, which aims to improve literacy and nutrition while reducing the short term hunger of school age children.

This is where going beyond traditional social protection approaches to a more child sensitive social protection approach becomes invaluable. If used correctly this approach can help children address diverse negative impacts emanating from the crises, via accessing quality services to support their protection, education, health and wellbeing together with financial assistance.

A social protection approach that is sensitive to children can help remediate economic exploitation of children as well as address other related types of violence against children during crises. Our systems need to go beyond traditional, adult-centric, bureaucratic and condescending approaches if our children are ever to recover from the impacts of these crises.