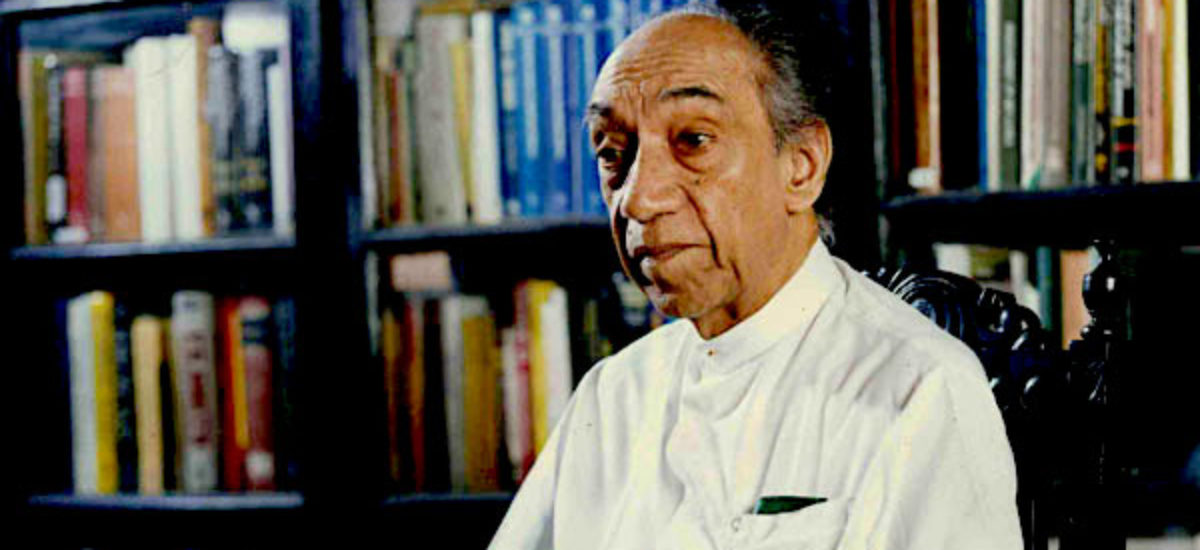

Photo courtesy of Daily News

Capitalist transition within a state is a process that involves changing institutions or the rules of the game so that markets become the primary mechanism for resource allocation. These changes must be legitimised at an ideological level. When institutions to establish markets are successful, they become ideas that seem to be natural and common sense, thereby creating a hegemony.

The establishment of the hegemony of markets is not a technocratic process but a political one. Conflict and struggles are always a part of this. These conflicts can be violent. The process of capitalist transition takes place in a particular society within its own history. This means capitalism is not some sort of a model. It is a historical process, influenced by political forces in a particular historical context. It takes place in a context of global capitalism.

Institutional changes to promote markets create social classes. Since the socio-economic impact of capitalism is always unequal, in Sri Lanka different sections of the Sinhala majority benefitted unequally from capitalist transition. In other words, although the Sinhalese were unified in ethnic terms, they were divided in class terms. The inequality generated by the capitalist transition within the Sinhala majority could always combine with Sinhala nationalism to oppose the regime in power. In a political space defined by ethnicity, the Sinhala majority was the deciding factor who came to power through elections. The opposition to regimes could also turn into an opposition to capitalism and a general opposition to the state itself.

Post 1977 is a new period of capitalist transition in Sri Lanka. It emphasised markets, the private sector and openness to global capitalism. It changed the process of capitalist transition from the state-dominated capitalism that characterised the 1970-77 period. Political leadership to the process was given by J.R. Jayewardene who led the United National Party (UNP) in the 1977 general election. Mr. Jayewardene saw the challenges that economic reform will face from the Sinhala majority long before 1977. In 1966, in the keynote speech to the 22nd annual session of the Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science, he argued for the need to establish a directly elected president to carry out unpopular economic reforms. A powerful president would be elected directly for a fixed number of years and be able to face opposition to economic reforms.

The UNP won the 1977 election securing 50.9 per cent of valid votes. This translated into 140 seats in a parliament of 168. In other words, it gave the UNP a degree of political power that was disproportionate to their voter base. At this point it is worth recalling how UNP the brought about this major change in institutions controlling the state using this power. Prof. A. J. Wilson’s book The Gaullist System in Asia: The Constitution of Sri Lanka (1978) gives details of how this happened.

The election was won in July 1977. On September 22, the government put through an amendment to the 1972 constitution that established a directly elected president as the head of state. Mr. Jayewardene, who was elected as prime minister in 1977 general election, became the first president. This bill was not even discussed by the government parliamentary group. It was discussed only at cabinet level, adopted by what then was known as the National State Assembly and certified by the Speaker on October 20, 1977. There were only six speeches in parliament when this fundamental change to the structure of the state was instituted. Then a parliamentary select committee was appointed in November to draft a new constitution. This was totally under the control of the UNP. The select committee held only 16 meetings. There was no serious effort to get public participation. A questionnaire that was circulated received 281 responses. Sixteen organisations and a Buddhist priest presented evidence before the committee. The report of the Select Committee was tabled in June 1978, debated in August and the 1978 constitution became law in September 1978.

It is clear that what determined the establishment of the constitution that still rules over us was the political power enjoyed by the UNP. Often the key role played by the balance of political power in establishing these institutions get masked by discussions on legal aspects. Balance of political power is the key in forming constitution. Linda Colley’s recent book The Gun, the Ship and the Pen demonstrates this by analysing the history of constitution making in many parts of the world.

Once established, controlling the presidency became the most important political objective for the Sinhala political elite who controlled the state. Although politicians criticised the presidency when out of power, they were reluctant to give up this power when they became president. A powerful presidency existed in a society where there was little possibility to challenge the power of the president through societal mechanisms. In addition, factors such as patronage politics, which seeped into all spheres of social life, and a traditional attitude of looking towards powerful leaders for solutions made this office even more powerful. As soon as this kind of powerful centre of power was created, these factors generated a political culture based on loyalty towards the centre and the person who became president.

The second institutional mechanism that enhanced the despotic power of the state was the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). This was established just one year later, in 1979, to deal with the Tamil separatist threat to the state. It also normalised a discourse of terrorism. Although it came about because of a different issue, it has been used to deal with opposition to economic reforms in Sinhala majority areas. Reforming it or totally getting rid of it has been a consistent demand from those who have opposed state repression. But even after four decades, the political elite who control the state is not ready to give up the power that the PTA provides. In post war Sri Lanka, the power that presidency and PTA give to the political elite who control the state is enhanced by well-developed security forces. These now absorb a significant amount of resources of a state facing fiscal problems.

The presidency and the PTA have been part of the state for more than four decades. An account of the social impact of these in Sinhala majority areas is a study on its own. What we have are largely reports of individual incidents and numbers. A social history of this violence will reveal the true nature of state-society relations in Sinhala majority areas in the post 1977 period. This is a task for future researchers. We need similar research on the social impact of efforts to consolidate the territory of the Sinhala nationalist state threatened by Tamil separatism.

This year, the inability of the state to satisfy the demands of global financial capital has led to social unrest. This is a part of a global capitalist crisis. Several other factors, such as the situation Ukraine, have complicated the situation. A BBC news item reports that there have been various forms of social unrest because of economic discontent in 90 countries. For those who know the history of capitalism, this is not a new situation. What is important is to focus on how the ruling political elite respond to the situation. What we are witnessing now is a repetition of the same strategy of dealing with protests by using the coercive power of the state provided by the presidency and PTA. The scale of suppression might be different from what happened in the past but the political economy is the same.

A key demand for any kind of progressive movement in this situation should be getting rid of both the presidency and PTA. It should be total removal of these institutions and not any kind of reform. The latter only goes to further legitimise these institutions. Continuous criticism of the various discourses that currently legitimise these institutions will be essential. For example, the use of the term political stability without clarifying how this to be achieved is opening doors for state repression. Instead, what we need is a regime that seeks to establish political legitimacy with a new social contract. This is necessary not only to promote democratisation but also to promote social justice and pluralism.