I’d like to say this is the beginning of the end but it’s not. The latest spate of protests to hit the country has now been going on for more than a week. The protests have targeted one thing and one thing only: the Rajapaksas’ exit from power. While some argue we need to go beyond this objective and ask all parliamentarians to resign, others point out the difficulty or impracticality of such campaigns. Meanwhile Colombo’s middle class teenagers are busy formulating plans for the future. Some are talking about chasing rogues away while others are thinking of launching youth-driven political parties.

Let’s be honest. Before last Thursday, with power cuts below seven hours, the suburban middle class – English-speaking but not overwhelmingly so – were willing to grind their teeth and endure. Obviously they had no choice. Already inconvenienced by gas and fuel shortages, they suffered from other woes. One characteristic sample of this group came out demanding that enough power be supplied for him to watch Netflix after a long day’s work: “I know it’s a privilege to be able to afford Netflix,” he ranted, “but we deserve it as much as others.” Sweating in the dark, with some of them stuck in complexes and flats, they realised they could do very little about what was happening.

Then the power cuts shot up to 13 hours. For a population that threw their rage at Ravi Karunanayake for ordering two-and-a-half hour blackouts in 2019, this was more than unbearable. It was intolerable. Perhaps it struck the middle classes the most but all of a sudden protests were organised, gatherings were called for, and catch phrases that had been the stuff of memes were turned into symbols of anger. If you analyse the Mirihana gathering, you will realise that every hour or so brought in different layers from Colombo’s suburbs, and that it began with a professional and educated middle class protesting not just the shortages but Mirihana’s exemption from power cuts.

What did these protestors want? They wanted the government to go home. They have been saying that for the last one-and-a-half years. Many of them claim they saw the present crisis coming and are now playing the part of Cassandra. They have been hemmed in on the one hand from shortages and severe inflation and on the other from import restrictions. These deprivations are now dictating the trajectory of their protests; by the time Mirihana began unfolding, they were planned much larger demonstrations for Sunday.

Pushed into sheer desperation, an otherwise protest-resistant middle class sided with student activists and various other inner city groups. For a few days and nights at least, they were willing to let go of their class identity and embrace a movement aimed at toppling a much reviled government. The irony here should not be lost on anyone – in effect, the same middle class that watched on gleefully as the police baton charged student activists under the previous government are now holding hands with those same activists.

What are we to make of such developments? It’s important to recognise their progressive potential before anything else. Over the last few months, the most vocal defenders of this regime have gone quiet. Predictably, there have been a few murmurings of protest among its biggest supporters, especially its ideologues. This is why the curfew was so laughable if not counterproductive since on social media and in public the likes of Charitha Herath and Roshan Ranasinghe expressed dissent and made their exit while Namal Rajapaksa tweeted that he disagreed with his uncle’s social media block. To defend this administration in such a context would be to back a dead horse, not so much because it has run out of steam as because nothing it has done and is doing can justify its grip on power.

Ironically, the government has undermined the very ideals that brought it to power. On the one hand, despite much rhetoric about national dignity, we are entering into one deal after another with one country after another. We have not been told of what these deals entail and whether they will take a toll on Sri Lanka’s sovereignty. On the other hand, a regime that sported its nationalist credentials have, over less than a week, drained the people of their love for the army owing to its deployment of the military against protestors. Perhaps the most popular catchphrase of the SLPP campaign was “ranawiru gaaya” or love for the war heroes. Now all that is gone; even the most fervent supporters are siding with activists and protestors, claiming themselves to have been cured of such “gaaya.”

These are certainly failures of governance. Yet while critiquing them, I think we should be subjecting the protests to constructive critique as well. I say that because we’ve seen this happen before, albeit on a smaller scale. What was the 2015 election about, after all, other than a concerted effort against the Rajapaksas and their wretched excesses? Yet notwithstanding the enthusiasm that marked their defeat that year, the reformist administration brought in their place disintegrated barely a year later. That was due to two reasons: an obsession with personality over policy, which focused on keeping the Rajapaksas not just out of politics but out of parliament and the democratic mainstream and a failure to recognise the crisis as one of systemic proportions, rather than of corrupt politicians and parties.

The second point merits much reflection. By reducing the ills of the Mahinda Rajapaksa regime to the Rajapaksa family, the yahapalana government gave the impression that all it needed to cure the country of political corruption was to send them out and away. This is why it entered into deals with, and handed ministerial posts to, former Rajapaksa loyalists, something that got the yahalapanists mileage but cost them credibility.

When the yahapalanists tried to regain their momentum in 2019, after a long constitutional crisis, the Easter Sunday attacks happened, putting an end to the idea of a second term. The SLFP’s socially progressive potential, meanwhile, had been forestalled by the UNP’s capitulations to the neoliberal right, epitomised fittingly by the image of Mangala Samaraweera and Eran Wickramaratne holding a placard bearing their fuel price formula at a press conference. In the end Gotabaya Rajapaksa got to monopolise the security and sovereignty debate, an inevitable consequence of reformist politics that linger on issues of corruption to the exclusion of other more material, systemic and structural problems.

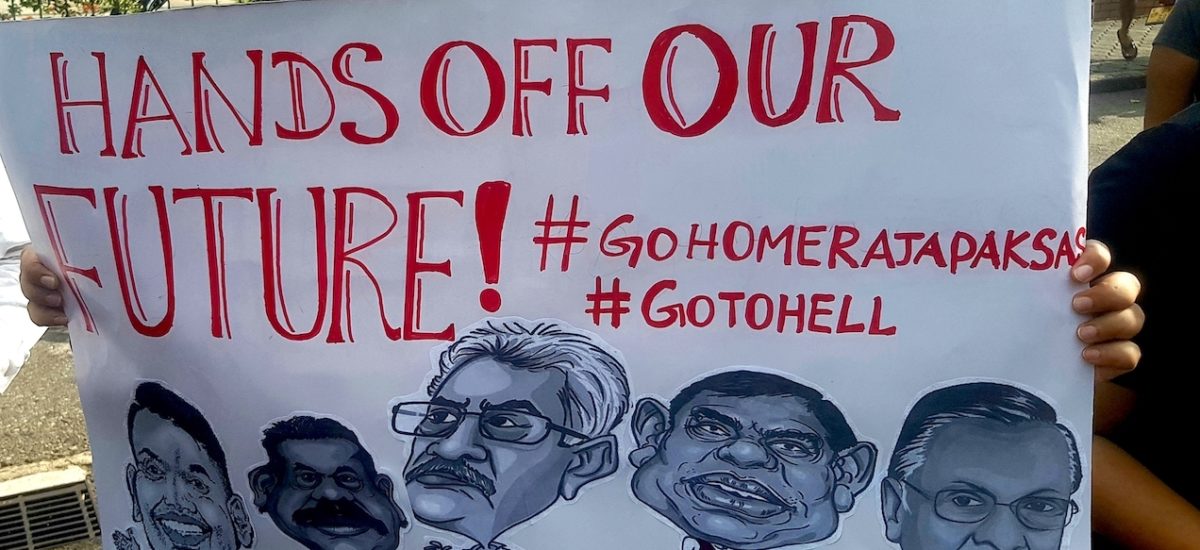

History tends to repeat. Today we are seeing a repetition of all this in the protests against the Rajapaksas. I don’t include all the protests because there are many of them, some in Colombo, many outside. Not surprisingly, the Colombo protests, in keeping with the class composition of those who live in and transit there, have turned into big match parades. What started out with much promise and aplomb have reduced to a set of people holding slogans and out-sloganeering others. These are the trappings of a typical middle class anti-state campaign, not necessarily cut off from the rest of the country, but not linked as much as it should be there. Focused on the corruption of a few, middle class demonstrators are fixated entirely on driving Gotabaya and the rest of his clan out.

The situation is different in the villages. There the fury and the rage are real. People are not holding placards and organising pageants. They are storming the metaphoric Bastilles that the Rajapaksas have erected around themselves. In 2015 hordes of voters went and cried with Mahinda Rajapaksa when he lost the presidential election. Today these same people, and their progeny are defying the police and running to Carlton, full of righteous anger. In Polonnaruwa, a group of voters stormed and destroyed Roshan Ranasinghe’s house. Many miles away in Kesbewa, they burnt a hoarding in front of Gamini Lokuge’s house. These are not isolated incidents; they are linked, connected, symbolic of a new beginning.

Meanwhile brought together by unions and collectives, garment workers are going beyond Colombo’s fixation with the Rajapaksas. Their rallying cry is, “Bring the dollars we earned for you back!” The “you” isn’t a reference to the Rajapaksas, rather to the company bosses who lent their support, overtly or tacitly, to the first family. These bosses and their acolytes have been as complicit in entrenching inequalities as has the political class. In late 2020 after the second wave hit, for instance, they connived in busting unions, in forcing factory workers to report to work despite obvious health risks. These workers possess the one thing Colombo’s middle classes lack, namely, organisation. They should hence reach out.

The demonstrations have taught us some important lessons. The Rajapaksas may or may not go out with a bang or a whimper. Yet the needs of the country extend beyond their exit from politics. In the eyes of Colombo’s middle classes, they have overstayed their welcome and they need to vamoose. But for estate workers and garment workers, the struggle has transcended the excesses of one family. This is why these protests should shift from urban centres to peasant and working class heartlands. The Colombo protests are unorganised and are running the risk of deteriorating into big match parades. As an activist friend put it, “life in Colombo has always been a big match.” Life elsewhere, however, has not.