Photo courtesy of Nimanthi Perera-Rajasingham

This is a revised excerpt from Nimanthi Perera-Rajasingham’s book, Assembling Ethnicities in Neoliberal Times: Ethnographic Fictions and Sri Lanka’s War

Today Sri Lanka faces its worst economic crisis since independence. In the coming months, people’s hardships will only worsen as more austerity is forced on them. The present crisis is a result of 40 years of free market economics. Since 1977, the Sri Lankan state, across party lines, has expanded what David Harvey and others have theorized as neoliberalism or “a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well being can be best advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets and free trade. The role of the state is to create and preserve an institutional framework appropriate for such practices.”(1) Within this framework, Sri Lanka has come to be more and more exposed to global forces and trends, has deprioritized national production and ignored the needs of its actual citizens. The argument that markets can best determine the value of everything has led us to this difficult place.

I want to focus on how this model of development, implemented in the North and East through the expansion of the international tourist industry soon after the war ended, continues to negatively impact Tamils (even though it was apparently bringing peace through development), and expanded a state-military-corporate penetration into the region that weakened the economic rights of communities. Such a rapid expansion toward futurity was accompanied by a cultivated amnesia about Tamil rights, questions of war reparations, demilitarization and the disappeared. This forced amnesia is resisted strongly in Thamotharampillai Shanaathanan’s, The Incomplete Thombu, and attention to his memory work invites us to question the value of an economic model based on the expansion and penetration of global capitalism to a community still struggling with loss.

Postwar development: Tourism in Passikuda

The tourist industry today is seen as a savior because it earns much needed foreign currency. However, this narrative only makes sense within a neoliberal model of development. If the rights of people living in the North and East had been the focus, then international tourism would be seen as ill-suited to a people struggling to come to terms with years of war. If we critically focus on the very messaging the industry promotes, we can see how harmful the industry has been.

Because of three decades of war, the Passikuda beach in Batticaloa had no hotels or tourism in 2009. Fishermen had lived by Passikuda and continued to go out to sea even after these beaches became High Security Zones guarded by the navy. Despite conflict and even the post-tsunami rules that curtailed their access to the sea, the fishermen still continued to fish. It is ironic that it is the end of war, and “peace” that finally threatens their way of life. For immediately after the war ended, then Minister of Development Basil Rajapakse arrived in Passikuda to survey plots of land to be sold or leased to corporations for the construction of tourist hotels. As the fishermen in the adjacent Kalkuda village told me, they were not part of discussions regarding the future of their beaches. Furthermore, the armed forces do more today than simply make the commons accessible for grabbing and privatization: the military has actually joined with corporations to run hotels, guesthouses, and canteens, often denying local populations access to these economic activities.

To further unpack how this industry impacts Tamils, we only have to carefully read the very literature the industry produces to sell itself through the use of Tropical Modernism. The hotel’s website boasts with apparently no irony that the Maalu Maalu is “a quiet getaway… on an untouched stretch of white sandy beach.”(2) As in the case of colonial travel literature that boasted of empty lands available for occupation, the camera prospects land from above, emptying the place of local people. The needs of local people and their experiences of war and violence are refused. By using a Sinhala word Malu, the hotel suggests it is engaged with the local community, but we know that this is a Sinhala word, and the choice is not accidental.

In terms of architectural style, Tropical Modernism is a style that Tariq Jazeel defines as an architectural movement in Sri Lanka that opened up the colonial house and built with tropical nature rather than in opposition to it to vernacularize form.(3) Yet, despite the use of a form originally intended to decolonize space, the built environment re-performs the hotel’s history of expulsion. The hotel boasts that the design for the chalets was “inspired by the traditional ‘waadiya’ of the fishing village.” Ironically, this architecture entrenches neoliberal corporate violence against them. For tourists to inhabit these waadiya-inspired rooms, actual local fishermen have to be disappeared from these beaches. Because tourists stay in these rooms, fishermen cannot freely be on the beach.

The design of Maalu Maalu is even more ironic, however, because the actual fishermen’s waadiya is right next door, sidelined. As the chairman of the fishermen’s co-op explained to me, when numerous hotels kept popping up on the Passikuda beach, the fishermen were moved from their usual fishing bay to a spot by Maalu Maalu. In 2015, as the land behind this spot was sold to a private investor, they were told that they would have to move again. The fishermen collectively resisted this second attempt to displace them, and have won their rights to stay for now. The hotel and the actual fishermen’s waadiya should clarify the structural inequalities between them, for it is as if one form has sucked the life out of the other.

The Incomplete Thombu or the Knowledge that Things Hold

Against the logic of the corporate-military-state industrial complex, that attempts to produce cartographic knowledge, Shanaathanan’s work reinfuses people and landscape with vitality and refuses the dominant amnesia that neoliberal peace offers.

The Incomplete Thombu emerged in the postwar period out of two previous projects that Shanaathanan had curated in collaboration with other artists and Tamils from Jaffna and Vancouver. The first, “History of Histories” was curated in 2004 at the Jaffna library. When the reconstructed library opened in 2003, there were many empty shelves, and the exhibition was a kind of replacement for the burnt books. Shanaathanan and other collaborators of this project went to 500 homes to collect objects to be placed in glass bottled and shelves. These collaged things bore witness to the history of this building and the history of violence that many Tamils and Muslims in the north and east experienced. Shanaathanan explains the project as follows: “The collection included a wide range of ordinary, mundane objects such as a single shoe of a dead child, the broken head of a temple icon, various kinds of identity cards, passports, death certificates, reports of disappearances, letters of missing relatives, keys of the houses that were demolished for the expansion of the “high security zones,” police residential permits, photographs of loved ones lost in the war, the ashes of a burned house, particles of trodden buildings, shell-pieces, bullets, broken dolls, pieces of dance and costume jewellery, barbed wires, water, sand and so on.”

This assemblage constitutes objects that we might generally call junk or scrap, economically worthless things having little commodity value, but greatly treasured and loved by those who kept them through displacements and war. People carried these things with them to their new homes to make their lives as refugees bearable. When Shanaathanan was in Vancouver on residency in 2013, he curated a similar project at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of Vancouver called “Imag(in)ing Home,” where he invited Tamils living in Vancouver to bring an object each that reminded them of home. Both these projects refused to erase the violent past but bore witness to loss.

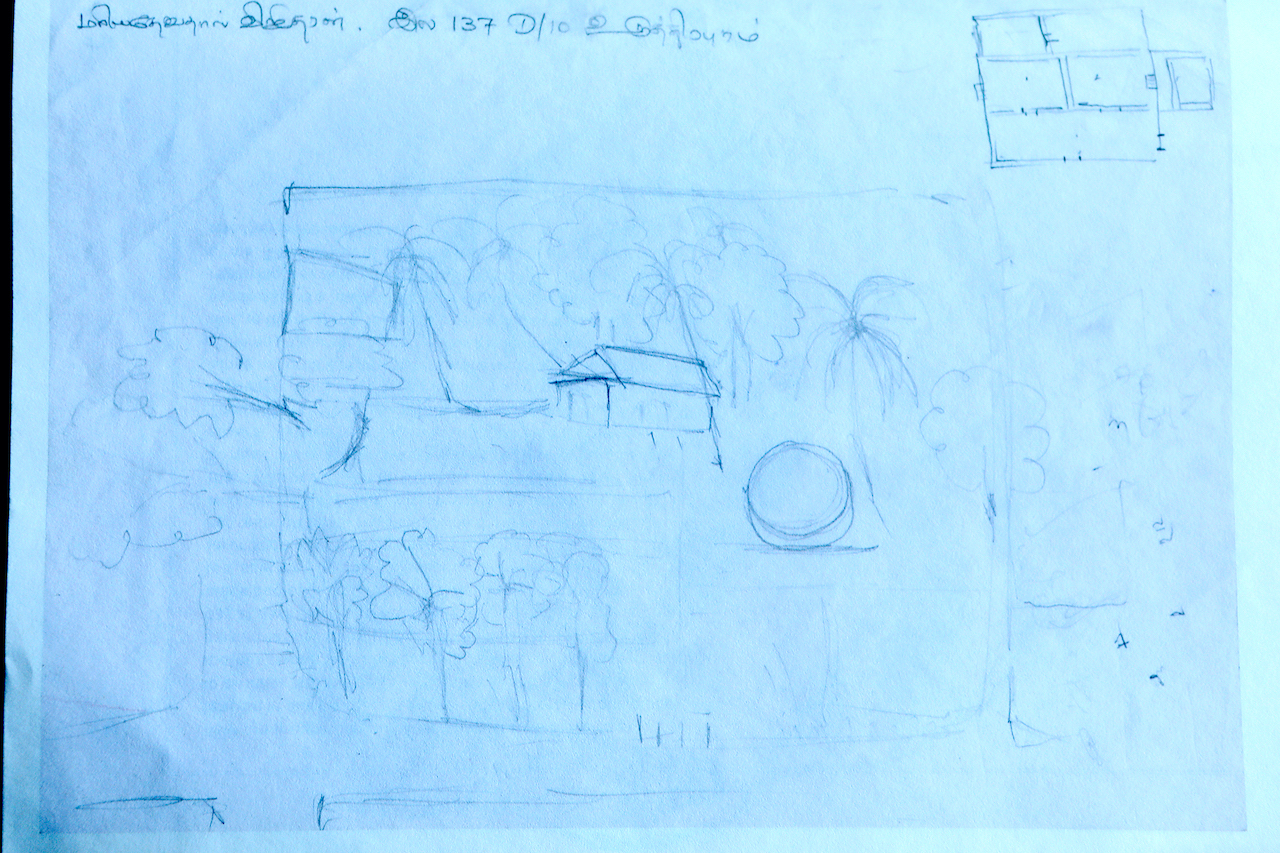

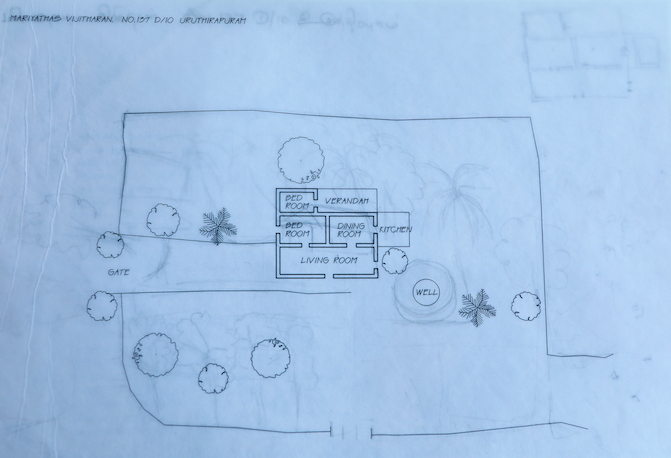

In The Incomplete Thombu, Shanaathanan shifts more deeply to offering his own embedded art as an alternative way of thinking peace in non-commodified form. For one, as a book, it takes art to people, rather than asking people to come to the museum. Instead of asking each of the eighty people he interviewed to bring in an object as he had in the two earlier projects, in The Incomplete Thombu, Shanaathanan sketched images based on his subjects’ testimonials. As it states on the cover page, “the enclosed documents (1-80) are made up of three related elements: ground plans of houses drawn from memory by displaced civilians [with interview notes on reverse], architectural renderings of collected ground plans and dry pastel drawings made in response to all of the above.”(4)

Inner flap of The Incomplete Thombu

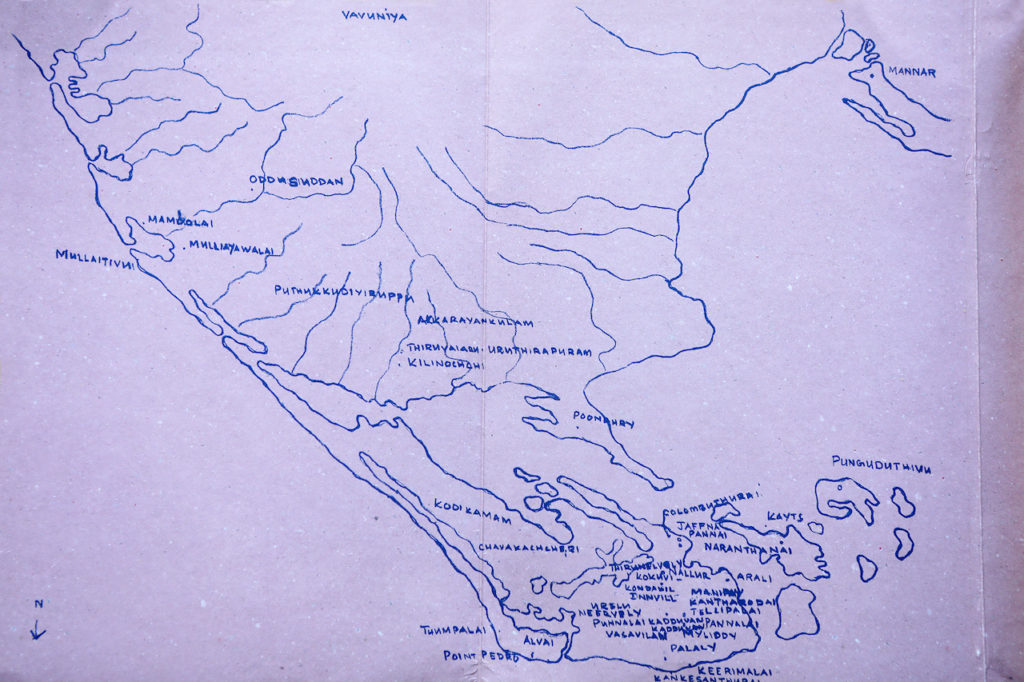

The book’s frame is an excellent place to start to think about how colonial categories are deeply implicated in contemporary ethno-nationalist violence. The book’s cover is made of pulp paper or pink craft paper and looks like an official government file. The inner flap of the book unfolds to display a Portuguese map of the north. Each location on the map is a place one of the eighty interviewees has been displaced from. The map flips the north-south trajectory of Lanka because Point Pedro, usually represented as the northern most tip of the island is in the southern most tip. The island has been flipped on its head, so the center of the island becomes Jaffna rather than Colombo, reminding us that maps are not ‘real’ but human creations. This map shows us that borders and boundaries, north and south, are products of human intervention, and not natural. As such The Incomplete Thombu draws alternative maps and writes different histories, but also draws our attention to how modern scientific knowledge and cartography were produced for colonial governance and rule.

The relationship between colonialism, modern scientific knowledge, and ethnic violence are embedded in the title of the book. The word thombu, refers to land registries created by first the Portuguese and then the Dutch. Thombu as such refers to the beginning of an ethnographic or positivist project to register lands and privatize properties. As Nira Wickremasainghe and R.A.L.H. Gunawardena have argued, it is with modern classification and enumeration in the 19th century through the census and ethnographies that modern notions of race and ethnicity came to be consolidated.

By adding “incomplete” to the title of the book, Shanaathanan suggests that he is continuing the project of documenting and listing but not in the spirit of the colonial registries of land, but rather against the erasures of a state-corporate-military assemblage that aims to dispossess people of their lands and belongings in the postwar period.

Take for example, the ground plans that accompany each testimony. The first image is a sketch of home made by one of the participants. A precise architectural drawing of it is then printed on transparent tracing paper, which is superimposed on the interviewee’s subjective drawing of his/her lost or destroyed home. The original drawing contains imprecision, impression, art, and memory, but the architectural map transforms these malleable features to produce sharp, clear, straight lines, and scaled drawings. Yet, because you can see traces of the hand-drawn sketch of the original below it, we are given insights to how maps are drawn from the subjective collection of information and impressions. The differences between the two ground plans are enormous. The Incomplete Thombu lays bare the structures of objective knowledge to refuse the claims of the state, which like the technologies of architectural mapping would like to wipe out the effects of war in the name of reconstruction and development.

Ground plans, 14

Drawing of home and architectural design overlap

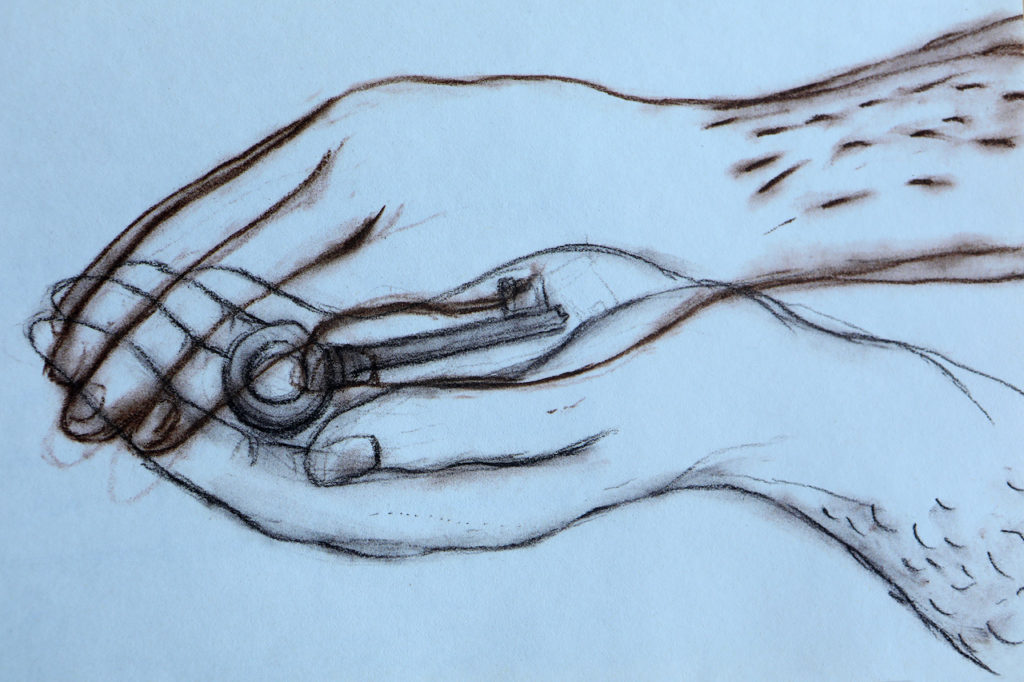

The most significant refusal of neoliberal peace is in the very touching and thoughtful sketches Shanaathanan makes out of the testimonies he heard. The sketches are of things dear to his witnesses, and function as gifts he makes to them in return for their stories and drawing of ground plans. If the state built giant war memorials of military power, then Shanaathanan’s sketches offer a different way to remember the war.

The first image is of two hands holding a key, which the owner of the key explains as, “My father carefully locked the doors and brought all the keys with him, with the hope of return. Now, almost twenty years have gone by, and my father passed away a few years back, without seeing the house. We still have the keys of the house even though it, and my father, no longer exist.”(5)

The sketch enfolds the key in the narrator’s two hands, which she lovingly holds in lieu of the destroyed house and now deceased father. The key, story and image tap into the affective labor embedded in the relationship between the narrator and his/her father and their lost home. It is an avenue by which the narrator of the story can remember and revive for us a life easily disposed of and forgotten by the state. The empty space on the page around the hands create possibilities for new significations as it invites us to fill it with our own responses to image, object and narrative. Even as this book creates a registry of lost land the reality is that for the narrator and her family, there will be no return to a place or time before this traumatic incident. Yet, their memory of home finds some space for expression to give new meaning to lost objects.

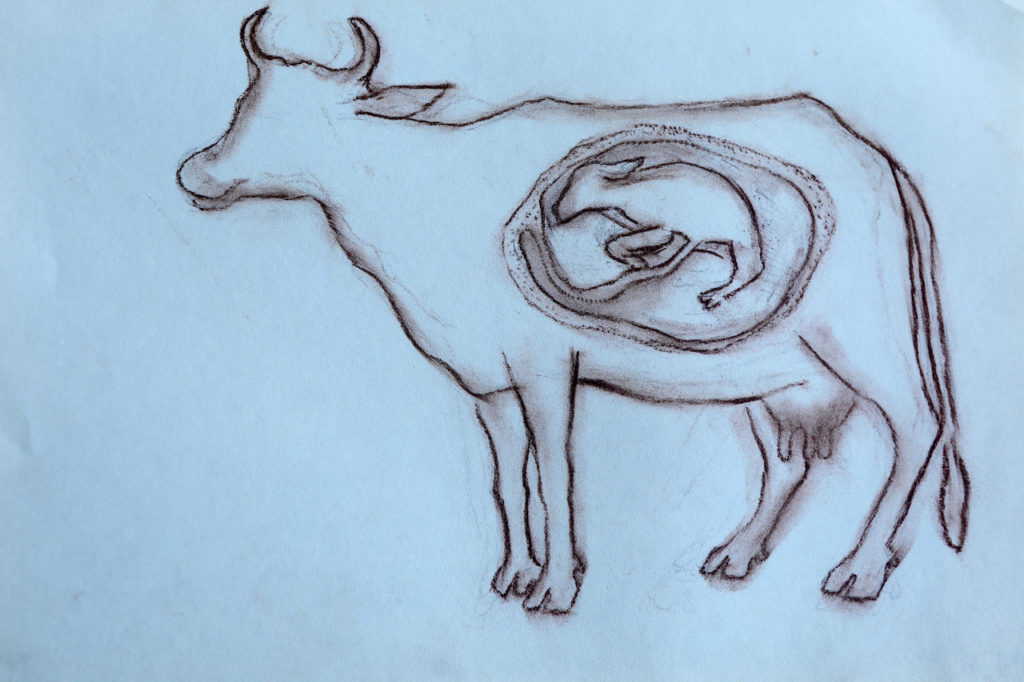

The second image is a sketch of a pregnant cow. The image is based on the testimony of one who still grieves that she never found out what happened to her cow when they had to flee their home. If the narrator’s traumatic loss of her beloved pregnant cow produces the cow as a thing around which melancholic emotions have revolved, then Shanaathanan attempts to heal this trauma by giving the narrator a representation of that lost thing. It is not quite a photograph, a mimetic image but a creative rendition of his or her lost cow and her calf, which would be normally impossible to see inside the cow’s womb. The drawing of cow and calf adds an element of unexpected, and gives back the narrator something memorable to remember the beloved cow by. Because it is art and easily moveable and storable, it need not be abandoned as the cow was, but has the potential to be an image that concretizes/materializes loss. The cow’s materiality is both offered and refused through the sketch.

I end with a story Shanaathanan told me in 2015 in his office at Jaffna University. One man he spoke to was an illiterate farmer. He had never actually held a pen, and so asked his son to draw a map of home as the father directed him. This was the first time that the father had ever told his son the story of his home and expulsion from it. The sketch of the home allowed the father to recount and remember his experiences of being displaced and for the son to bear witness to those experiences. Architecture, art, and object came to mean inter-generational communication. This remembering works against the amnesia that the Sri Lankan state tried to produce in the aftermath of the war, celebrating its victory and dismissing the thousands who died. The Incomplete Thombu reminds us that real peace and development would have to prioritize people who have experienced such loss and bend to their needs, not to the pleasure of tourists who want a quick holiday.

[1] David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism. (Oxford: OUP, 2007), 2.

[2] Tariq Jazeel, “Bawa and Beyond: Reading Sri Lanka’s Tropical Modern Architecture,” South Asia Journal for Culture1 (2007): 4.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Shanaathanan, The Incomplete Thombu (Amsterdam: Raking Leaves, 2011), cover page.

[5] Shanaathanan, The Incomplete Thombu, 16.