Image courtesy of Centre for Poverty Analysis

My daily commute to Colombo has been on hold for quite some time since my office adopted work from home as part of our work routine. If it is anything that I miss from my daily commuting, it’s the constant messages from UberEats or PickMe nagging me to get something to nibble while I get on with my day. However, it was rightly pointed out to me that I have been saving up quite a few pennies lately but I often ponder on whether this is the reality for other individuals and families. Who has been saving or borrowing more? How have people been coping with changes in working routines and the rise in prices over the past year?

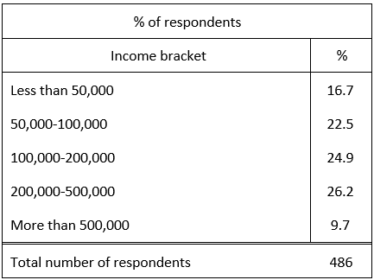

On average, the month on month inflation rate is around 0.3% (Department of Census and Statistics (DCS, 2021). This means the prices have increased by 0.3% in August compared to the prices in July. While the 2016 Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) highlights the average monthly expenditure for a family for food is approximately Rs. 19,114 (DCS, 2016), the price levels have increased by 6.7% since August 2020. (DCS, 2021). These increases surely affected people’s affordability, especially depending on levels of income and access to work. In an attempt to understand these effects more clearly, and to understand how different groups have managed through the lockdowns and various movement restrictions imposed, Centre for Policy Analysis (CEPA) carried out a series of online surveys. A closer look at the impact on livelihoods is drawn for the survey carried out between May and June 2020 with information for 468 individuals from around the country under different income brackets as given below in Table 1.

Total number and percentages of respondents for each income category. Income category “More than 500,000” is not analysed due to low response rate. Source: Centre for Poverty Analysis, COVID Survey Wave 1

Through the survey we were able to get a sense of the types of finances people utilized during first lockdown period to cover the needs of their whole household. As figure 1 (below) indicates, a majority of the respondents used cash at home and cash at bank as their first and second choices across all income categories. However, in terms of using multiple sources decreases with the increase in income. This is intuitive where individuals belonging to lower income categories (with less than Rs. 50,000 household income, and between Rs. 50,000-100,000) have had to resort to all types of finances available, including pawning and borrowing frequently, while the higher income categories have resorted to pawning jewellery or other methods of borrowing on a very limited scale.

The trend related to the types of finances accessed persists when the data is analysed according to the income group against locality of residence (categorised by Municipal, Urban and Pradeshiya Sabha areas) as well. This shows that even during the first period of COVID-19 restrictions, the lower income tiers maximized their savings very quickly and had to resort to other means to survive.

COVID-19 lockdowns have been hard for living conditions due to two reasons: the first is that income is disrupted to some extent and this affects some tiers more than others. It has been harder for daily wage earners and those who cannot work from home; a majority of them belong to lower income tiers and they rely on informal methods of income. The second reason is that due to disrupted production and other economic activities, prices of goods are relatively higher. This further acts as an unexpected shock that increases the burden to the lower income tiers. Safety nets and support to deal with crisis then become a much-needed service.

In terms of social safety nets, state sponsored COVID-19 relief packages were mainly in two forms: a bundle of essential items or cash of Rs. 5,000. Other packages, especially if individuals and households were affected by COVID-19 were also available. There was also support offered by private sector and civil society in numerous ways. According to the HIES data, in 2016, the cost of a bundle of essential items of rice (Rs. 847), vegetables (Rs. 1,884), fish (Rs. 1,820), meat (Rs. 920), pulses (Rs. 693), coconuts (Rs. 1,102) and fruits (Rs. 612) accounting for roughly Rs. 7,500 would suffice for a family of four per month. However, as the inflation statistics show the cost of food today is relatively more expensive than in 2016. Thus, it makes it clear that while relief packages certainly help, with limited access to savings and to work, families at the lower tiers have had to face serious hardships in making ends meet. Recovering and moving forward would require targeted support to assist such households and individuals who have been made more vulnerable by this crisis.

This article is the fifth of five published on the CEPA Blog as part of a series to understand the impacts of COVID-19 on poverty and inequality.