Photo courtesy of Rohan Wijesinha

In a media release dated October 21, 2021 Dr. Anil Jasinghe, Secretary to the Ministry of Environment, in requesting a National Eco-tourism Plan to promote the tourism industry as well as environmental protection, had this to say: “Sri Lanka has a vast flora and fauna biodiversity, pristine beaches and priceless ancient sites. The mangrove system can also attract a large number of tourists. But biodiversity is under serious threat due to the unintentional destruction by certain people in our country.”

While lauding the Government’s albeit late realisation that if protected and preserved, the rich biodiversity of Sri Lanka attracts valuable foreign exchange for this country, his reference to the fact that this is all under threat due to “…unintentional destruction by certain people…” does give cause for wry amusement. We all know who these certain people are.

The blessings of The Gathering

The Minneriya National Park is famous internationally for The Gathering, the largest seasonal congregation of wild Asian elephants. In 2011, Lonely Planet declared it as the sixth greatest wildlife spectacle in the world. This usually happens during the months of drought from August to October when over 400 elephants may be seen, at a time of an early morning or evening on the exposed grasslands of the reservoir. They are drawn here in search of food. The waters of the Minneriya and Kaudulla Tanks are released during the dry months for agriculture downstream and the receding waters expose acres and acres of fresh grasslands, vital fodder for the wild elephants of the region. The reservoirs drop to approximately 30% of their capacity but their great volumes mean that there is plenty of water still retained in them until the rains return for use by both the local human communities and the wildlife of the park. When the monsoon does turn at the end of October and as the water levels rise, the elephants disperse to other areas, usually to the adjacent Hurulu Eco Park, now lush with new growth from the refreshing rains. And so the annual cycle continues not just for the wellbeing of the elephants but also for the local human populations who benefit from The Gathering.

In 2016 Srilal Miththapala, former President of the Tourist Hotels Association of Sri Lanka, estimated that The Gathering earned approximately Rs. 4.4 billion for the local economy in just a few months of its occurrence; these included revenue for hotels, guest houses, restaurants and safari jeep drivers. The greater part of this was from the income earned from foreign visitors. The global Covid-19 pandemic, and the resulting collapse of the tourism industry, has temporarily ended this bounty, causing economic devastation to these communities. They pray for the day that things return to normal and tourists flock to Minneriya again to see this unique, natural happening.

Scattering The Gathering

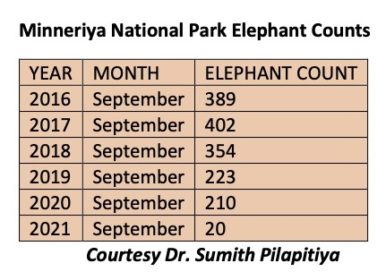

In 2018 the construction of the Moragahakanda Reservoir was concluded but the channels that were supposed to take its waters to the North and North West were, and still are, far from completion. A decision was made to use Minneriya and Kaudulla, downstream of Moragahakanda, as holding tanks for the excess water. Even at the height of the drought, they are now maintained at 70% of their capacity, although in 2021 the water levels were closer to 90%. The available grasslands have drastically reduced in expanse with significantly less than half as much food being available for the elephants. Unsurprisingly, researchers have recorded a large decrease in the number of elephants visiting Minneriya. Between 2017 and 2020, there was a 50% reduction. In 2021, there was a 95% drop with only around 20 elephants being seen in September. The Gathering has been scattered, with elephants seeking food elsewhere. This has exacerbated the human-elephant conflict with a six-fold increase recorded since the release of these unseasonal waters. There will be no return to normality for either the elephants or the local human communities unless sanity prevails and this natural wonder is allowed to happen once more. Who will now come to see a few dozen elephants get together at Minneriya, something they can see in any other country or national park that hosts this endangered species?

It must also be remembered that Minneriya and Kaudulla are to be used as holding tanks only until the channels to the North are completed. As such, no long term plans for agriculture may be made based on this temporary excess. The Gathering is to be destroyed for short term expediency.

Alien threats

Prior to 2018, an alien invasion had already begun to threaten the prosperity of Minneriya. The common cocklebur, known in Sinhala as agada, had been taking over the exposed beds of the Minneriya and Kaudulla Tanks. A weed that originated in North America, it entered Sri Lanka possibly through its adhesive burrs becoming attached to shipments from overseas. With no natural predators, it covered an estimated 20% of the reservoir bed. This means that prior to the excess water being released to Minneriya, there already was 20% less grassland for the visiting elephants. Every year, the agada spread over wider and wider swathes of Minneriya as well as Kaudulla at an exponential rate.

Time was of the essence if the spread of the agada was to be stopped. It had to be removed before the seeds matured and fell to the ground, to retard its re-growth. The Federation of Environmental Organisations (FEO), in partnership with the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC), has begun an operation to remove the agada from the reservoir beds of both parks. With the assistance of corporate entities and the kind contribution of a few individuals, hundreds of hectares of the weed have been removed, areas that have now grassed over again. Much more has to be done over a period of a few years to ensure the invasion is stopped, not just at Minneriya but also in places upstream from where the seeds flow in. The DWC has now taken on this operation on their own.

Twin tragedies

The extended reduction in the availability of food has already had a tragic impact on a special family of elephants in the region. In July 2020, the first conclusive recording of the birth of twin elephants in the wilds was confirmed – a male and a female. They were frequently sighted until December 2020 when, with the coming of the rains and the seasonal range changes of the herds, the twins and their mother were not seen for a few months. Finally, in August 2021, their herd was spotted again. One twin, the female, was missing. The sad conclusion was reached that she had perished.

In December 2020, it had been noticed that the male was in slightly better body condition than the female. Still dependent on mother’s milk, the male seemed the more aggressive feeder. Baby elephants require approximately three gallons of milk a day and although they will start to experiment with grass and leaves at about four months old, they will continue to drink milk for up to two years. This means that the mother has to produce an adequate volume of milk during all of this time, not just in quantity but in quality too. Despite several allegations that the baby had been stolen or killed, the true reason for the female’s demise is most probably that her mother was unable to produce enough milk for both her and her brother. In nature, and even in the human world today, survival is to the fittest.

The silence of the major stakeholder

Tourism contributes to approximately 5% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the country and, as Dr. Jasinghe correctly points out, the industry is mainly driven by the rich biodiversity and natural wonders. In such circumstances, one would have expected the tourism industry to cry foul, loudly and insistently yet it seems to have left the protests to conservationists, not just in the saving of The Gathering, but also to plead for all the other natural wonders that are being encroached on and destroyed almost every day. In 2021, on average, a wild elephant has been killed every single day! The wild creatures and wilderness of Sri Lanka are currently facing the greatest peril they have ever been exposed to in the long history of the country. Yet apart from a few, the overall response of the industry to this mass scale destruction has been non-existent. This is despite the fact that the mindless determination to devastate the environment and biodiversity will lead to the annihilation of the tourism industry. Instead, the industry continues to concentrate on the outdated and unsuccessful, that of trying to bring as many tourists as possible at the cheapest possible rates in competition with other countries that do it even cheaper and better. Ironically, it continues to do this by advertising the same natural wonders despite the knowledge that, at the present rate and in a few years’ time, it may all be destroyed. Like its political masters, the tourism industry seems to believe that this is the final generation and saving anything for the future is of little necessity.

The global pandemic has had a profound change on the attitudes of those who were once happy to just sit in the sun, on a beach and soak up the heat. New generations of travellers are now seeking a total experience to gain an understanding of a place, its history, its culture and, most importantly of all, its natural wonders. They seek to build memories of a lifetime. In other words, they seek quality and not quantity and will be happy to pay the necessary price for the added experience. This time of enforced isolation was ideal for the tourism industry to realign its objectives, strategize and move away from just building more and more hotel rooms that remain largely empty. Instead, it should have planned on how to attract the new traveller and give them such an experience that they would tell others about it and return again and again.

The days of mass tourism are over and if Sri Lanka continues to focus on bringing in numbers on cheap packages, it is doomed. The clientele for such holidays are rarely interested in the country or wish to contribute to it financially or emotionally. They will come, take and leave…and never come again.

What of the guardians of conservation?

In 2018, the Mahaweli Authority, who is responsible for the flow of water from Moragahakanda, publicly expressed its willingness to control the volumes released to Minneriya, so as not to endanger The Gathering. In 2019, a representative of the DWC was appointed to the Water Management Committee that decides on water releases to all reservoirs. One wonders why they have been so spectacularly silent while this wildlife conservation and economic catastrophe was being mooted? The DWC is the only statutory organisation with sole responsibility for the protection of wildlife; it should have championed the control of the water levels of Minneriya and Kaudulla long before now rather than leave it to conservation groups to play this role.

It is learnt that a delegation from the Mahaweli Authority recently visited Minneriya, having been re-appraised as to the problem by a wildlife enthusiast, and not the DWC. It is hoped that some long term good will come of it.

Intentional or unintentional?

The definition of the word intentional is when an action is deliberate and done on purpose. Accordingly, when something needs to be done but is ignored, then that too is a deliberate decision and falls under the definition of intentional. The actions, or lack of them, that have brought about this crisis at Minneriya are clearly intentional and the architects are known.

Dr. Jasinghe deserves much credit for reiterating the importance of biodiversity and the protection of it for the economic wellbeing of the country. At a time when it seems that the statutory bodies for conservation have largely abrogated their prime responsibilities, it is comforting to know that the Secretary to the Ministry of Environment is aware and is calling for change. With good governance and sensible dialogue and the knowledge gleaned from science and research, the impending disaster at Minneriya can be avoided. For that it needs intent and the concerted action of all the stakeholders involved. The future depends on it.