Photo courtesy of Facebook

Today is the International Day of Forests

“Knowledge is power: You hear it all the time but knowledge is not power. It’s only potential power. It only becomes power when we apply it and use it.” Jim Kwik

These are strange times when a Government stands by and watches while its natural resources are stripped away by those who have much to gain while the country has even more to lose. The utterance of weak platitudes has no power to stop the destruction, just as much as some carelessly tossed words brought it all on.

In 2021, according to press reports, 66 wild elephants have been killed in almost as many days as their habitat is being increasingly encroached on and their desperate search for sources of food takes them close to human habitation and cultivation. In 2019 Sri Lanka achieved the unenviable record of the greatest number of deaths of humans and elephant, 122 of the former and 407 of the latter because of the human-elephant conflict. The country with the highest incidence of human–elephant conflict in the world this year may see the achievement of even greater number as forests are decimated and ancient elephant ranges are blocked by unplanned development.

What can we do?

When Revatha, that magnificent tusker of Kala Wewa, was killed by electrocution, media and social media were inundated with his picture and those lamenting his foul murder. What next? Do we just sit by and wait for the next tragedy? What can be done?

Doing nothing is as bad as wielding the axe that cuts the forest and the future will curse us for it. For this is about securing the future for our children and for theirs. When those who make policy cannot see beyond the length of their life spans, then those more enlightened must act to ensure that that future is preserved. This is the responsibility not of the young but of the old who have been responsible for letting things slide to this state. For when the State does not care, then its people must, and remind the State that it was placed there to serve the people, not itself.

In a political system where ideology has been replaced by ego, the increasing public opposition to this environmental carnage, predictably, manifests itself in insecurity among those in power and they and their stooges lash out at those who speak up against them; the latest being a 19 year old woman who had the audacity to lament, on television, that trees were being cut in the vicinity of her home on the borders of the Sinharaja Rainforest. The whole machine of State seems to have been turned against her with statements been taken by the police and even by officials of the Forests Department, who accused her of not knowing what she was talking about. It seems that there are powerful forces that have investment in this area and have the political backing for their venture. Vilified, accused of being a political pawn of the opposition, the final straw is a suggestion, shared on social media, that she be stoned to death. How familiar is this, when women challenge the powers of a patriarchal system – not just in Sri Lanka but the world over?

In such an atmosphere, it is not surprising that there is some anxiety in expressing ones views. In numbers, however, lies the strength, and in addressing facts, not rumour.

Banding together

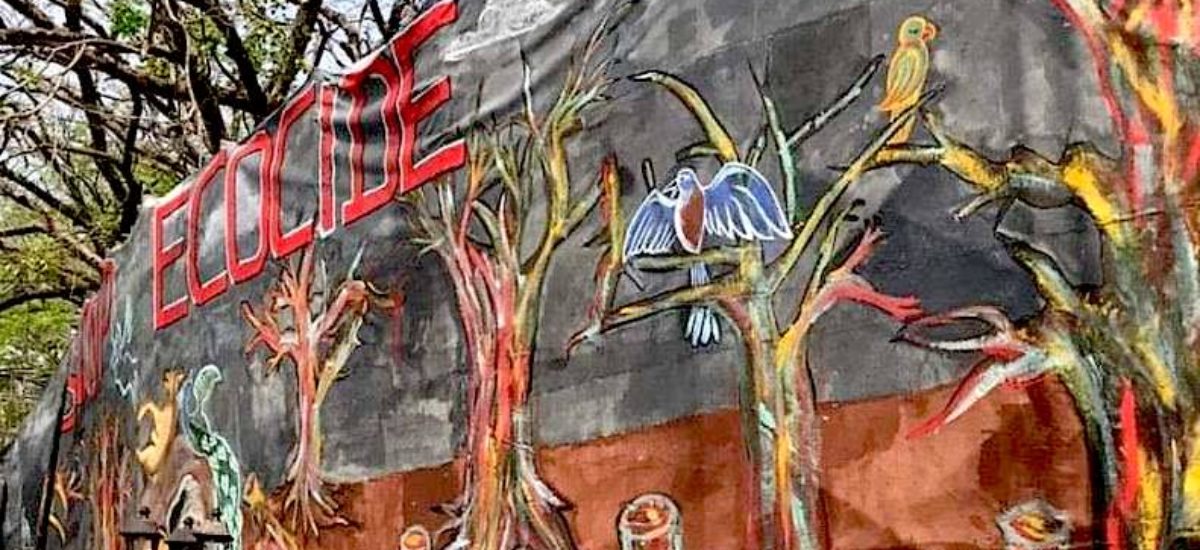

There are so many instances of destruction from so many different parts of the country reported on a daily basis that no one organisation, however strong its infrastructure and however distinguished its origin, can address on its own any more. It is together that they are strong and a dozen or more of these organisations have banded together to form the Coalition Against Ecocide (CAE); ecocide being defined as the destruction of the natural environment by deliberate or negligent human action. They welcome members and joining and supporting them is the most effective way of making one’s voice heard. It should not be forgotten that 6.9 million of the population voted this Government into power to serve the people; they are accountable to these people. Destroying theirs and their children’s futures is hardly the best way of rendering this service. Ask them to stop – in letter, in voice and in united action.

For if one places aside the plight of elephants and other wildlife that are being directly affected by this rampant deforestation, what of the other ecosystem services that these forests provide humanity with? The most important function of the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) is that of protecting the major watersheds of this country. From the Peak Wilderness and other mountain forests down to those on the coastal belts, all serve humanity with one of the vital elements of life – water. The mountain forests attract the rain while those lower down control and channel the flow of the rivers to the sea, slowing them down and diverting them, allowing absorption of moisture deep into the ground to replenish the water tables that feed the springs and wells that provide the water we drink and keep our crops alive.

A Sri Lankan politician once challenged another strong woman who was trying to protect a valuable wetland from destruction by questioning the importance of oxygen; after all it could not be eaten! Such is the absurdity of those to whom we sometimes give power. If forests did not absorb the carbon dioxide produced in the exhalation of most living species, as well as that produced in mega volumes by human industry, then we, as a species, would not exist. For in its infinite wonder of being, the trees of the forests photosynthesize this poisonous gas and release it as oxygen. It is estimated that a single tree produces sufficient oxygen to keep four people alive. They should be blessed with every breath we take.

We need development

Sri Lanka needs development but it must be sustainable and not jeopardize the future. We were promised science in political decision making, instead we have been given sciolism. Had science truly led the way, then rather than destroy natural systems efforts would have been made to preserve them for the vital importance they hold for our future existence. Existing fallow lands would have been utilized as development areas – areas not used by wildlife – to encourage human–wildlife co-existence rather than conflict. Above all, efforts would have been made to improve the quality of agriculture, particularly its productivity, which ranks as one of the lowest in the world.

This ecocide is being perpetrated in the name of farmers, to give subsistence farmers the opportunity to undertake chena cultivation on a wider scale. Subsistence farmers, for all of their hard efforts, are perhaps those on the lowest economic scale of this country. Hostage to the middleman, the produce they slave for is bought at a pittance with barely enough for them to survive until the next harvest. This is nothing but another way of trapping the poor in further, future poverty while gaining a vote for today.

Killing the golden goose

The importance of wildlife to the economy of this country, particularly of elephants, has already been articulated by members of the tourism trade. There is much financial benefit to be made, too, by those who have wildlife as neighbours. The only requirement is for some enlightened thinking. If those whose lands are habitually visited by wildlife could make an income from their visits, then this could subsidize the revenues they make from farming and considerably raise their standards of living and expectations from life. While the use of community fencing could keep them and their cultivations free from the raids of elephants during the growing times, the stubble left behind after harvest would attract not just elephants but other wildlife as well. A strategically placed tree hut, for example, given out to the discerning tourist who, post-pandemic, will be looking for an experience rather than just the run-of-the-mill holiday, could earn that farmer, in the fallow season, as much as he could earn from his harvest. In addition, Sri Lanka can attract an army of birdwatchers to its shores. With 492 species, 219 of which are breeding residents and most of whom live in forests patches adjacent to these farms, community-based wildlife tourism could provide added sources of income, with some basic training in nature interpretation. For this, forests need to be preserved.

The private sector needs to be a partner in such a venture by providing a unique experience for its guests, with minimal investment, while financially enriching these rural communities. In addition, communities that border national parks should directly benefit from being its neighbour with a proportion of the vast annual income from the gates being invested in those communities and not just sent to the local District Councils to be absorbed into some untraceable spending cycle. It is then that the park and its animals will become a benefit to them, and not a nuisance, and community conservation will become an actuality.

The stark reality, however, according to media reports, is that many of these forests are being given to corporate entities for large scale farming. Where is the escape from poverty for the local communities? Do politicians really want an emancipated peasantry? By what means could they then entice a vote? Let it be remembered that it is not just those in power now but the destruction of our forests has been a gradually accelerating process, over the past 70 years.

The power of the consumer

Large scale farms in these areas that were once forest will result in the local people being the poorer for it, economically and in the quality of their lives. These companies, however, need markets in which to sell their goods and partners with whom to work. If a boycott of their produce was undertaken by all who truly cared and if their partners, especially the international ones, were informed that their profit is from the outcome of the pillage of the nature of Sri Lanka, they then may think twice about what they do; consumers have every right to demand that the products they buy have been ethically manufactured or grown.

Likewise hotels and other leisure establishments that are built, illegally, in once forested areas, should be blacklisted and their overseas partners informed of the reasons for it. Who would want to see a forest while staying in a destroyed forest?

In the words of Clarence Darrow, “Lost causes are the only ones worth fighting for”. So when it seems that all is lost, there is hope if all can speak as one, especially when it is for a cause that will save the future for the generations to come; that is, after all, the essence of democracy.

Here are some of the forests found in Sri Lanka.

Photos courtesy of Namal Kamalgoda

(Please click on images)