Featured image by Hafsa Razi

One of the most contested issues in the debate around reform of the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) has been with regard to increasing the minimum age of marriage for Muslims. While legal reforms in 1995 increased the minimum age of marriage to 18 years for all citizens except Muslims, the MMDA does not stipulate an age of marriage. Contrary to popular belief, the minimum age at which a Muslim girl or boy can get married under the MMDA is not 12 years; as per Section 23 of the Act, a girl below 12 can be given in marriage with the authorisation of a Quazi judge. Hence, the minimum age of marriage for Sri Lankan Muslims is technically zero.

Of the problematic provisions of the MMDA currently being discussed, setting a minimum age has been met with so much resistance especially from conservative elements of the Muslim community. There are two points of contention here from within the Muslim community- one, whether or not the MMDA should set a minimum age of marriage given the absence of Islamic jurisprudence and consensus among scholars on the matter and two, if the minimum age of marriage should be raised, which age should it be raised to?

Opposition to raising minimum age

Those who are not in favor of the MMDA stipulating a minimum age of marriage give reasons mostly based on religious interpretations (and misinterpretations) of religious text and Hadith (practices of the Prophet Muhammed). In the past, the All Ceylon Jamaiyyatul Ulama (ACJU) made an appalling submission to Muslim politicians, stating that according to multiple verses in the Quran, there was “no restriction for age of marriage”. It also stated that according to their reading of hadith, “a father giving in marriage his daughter before puberty is possible”. The document also cited statistics that in Ampara district between 2011 and 2016 – 870 marriage involving 13-18 year olds had taken place, including eight 13-years olds and 36 14-year olds. While the document indicated that this number is low, it is actually very strong evidence against those who say that only one or two cases occur around the country. This figure also does not reflect the non-registered marriages, which according to community-level activists is highly prevalent.

Furthermore, the 2018 report of the 2009 Committee Appointed to Suggest Amendments to the MMDA [1] contains statistics of registered marriages with brides below 18 years for many districts around the country. This data shows the occurrence of marriages of girls as young as 12 even in districts like Colombo in 2014. The majority of marriages of minor girls are between 16-17 years of age, effectively proving that raising the minimum age of marriage to 18 years with an exception for 16 years will not resolve the issue of legal child marriages among Muslims.

Muslim lobby groups like the Muslim Personal Law Reform Action Group (MPLRAG) previously released a position paper advocating for no exceptions to the minimum age of marriage. They presented cases of lived realities and evidence of Islamic legal tradition that supports raising the minimum age to 18 years.

Lived realities of Sri Lankan Muslim girls

From field interviews conducted by researchers, women across many communities, counselors and volunteers who work closely with victim-survivors of child marriage, young mothers and women and girls affected by the Quazi court system have even articulated a much older age – 21 years. This is based on their experiences of how much this issue affects women and girls in their everyday lives and the benefits of having a legal protection against forced marriage, especially when consent of women and girls is not a mandatory prerequisite under the MMDA.

There are yet others who believe that the age of marriage should be set to 18 years, but a legal loophole should be in place, whereby under “special circumstances” a girl between 16 and 18 years can be given in marriage with parental permission and/or authorization of a Quazi judge. Special circumstances such individuals are referring to is mainly if the girl gets pregnant, or if the guardian of the girl is unable to take care of her and so on. These opinions are no doubt based on concern for the girls who maybe affected by these circumstances, but as evidenced by impacts of such legal loopholes around the world, such a provision if considered can have adverse consequences for 15 – 17 year old Muslim girls. Especially given that these are the ages whereby Muslim girls most likely drop out of completing Ordinary and Advanced Level exams, an educational milestone in determining their future progress. Bangladesh just recently permitted child marriage under special circumstances, amidst heavy controversy that it legitimises rape and forced marriages. In fact the first case under special provisions, was of a 25 year old man and a minor girl who got pregnant with his baby when she was 13 years old.

As evidenced by many cases around Sri Lanka of young Muslim brides abandoned, divorced or forced into polygamous relationships after being married as minors – child marriage with or without legal loopholes will not protect the rights of children, no matter how it is articulated otherwise.

A brief history of the minimum age of marriage

In light of such divergent viewpoints on a single issue (from many issues plaguing the MMDA debate) it is important to understand why Sri Lanka chose to increase minimum age of marriage to 18 years under the general law in 1995.

Prior to 1995, the General Marriage Registration Ordinance of 1907 and the Kandyan Marriage and Divorce Act 1952 permitted marriages below 18 years of age. In 1995, both these laws were amended and the legal age of marriage was raised to 18 years [2]. Despite the existence of a predated clause (Section 22 of GMRO), which indicated persons who must give consent for minors under 18 years to marry, subsequent case law clarified this legal anomaly. In Gunaratnam v. Registrar-General (2002) the Court of Appeal held, “Since the prohibited age of marriages has been raised to 18 years of age, the absolute bar to marriage must necessarily override the parental authority to give consent to the marriage of a party. It was not relevant whether parents agreed or did not agree to the marriage of their children, only persons who had completed 18 years of age could enter into a valid marriage.” Therefore the minimum age of marriage in Sri Lanka for all citizens except Muslims stands at 18 years, without exceptions.

Consequently, in 1995 the Penal Code was also amended raising the age of sexual consent from 12 years (previously) to 16 years given that this was the age at which individuals had the freedom to make decisions on education (de Silva 2009). Hence since 1995, under Section 363 of the Penal Code, sexual intercourse with a girl below the age of 16 is a criminal offence, however this provision exempts married Muslim girls between 12 and 16 years of age.

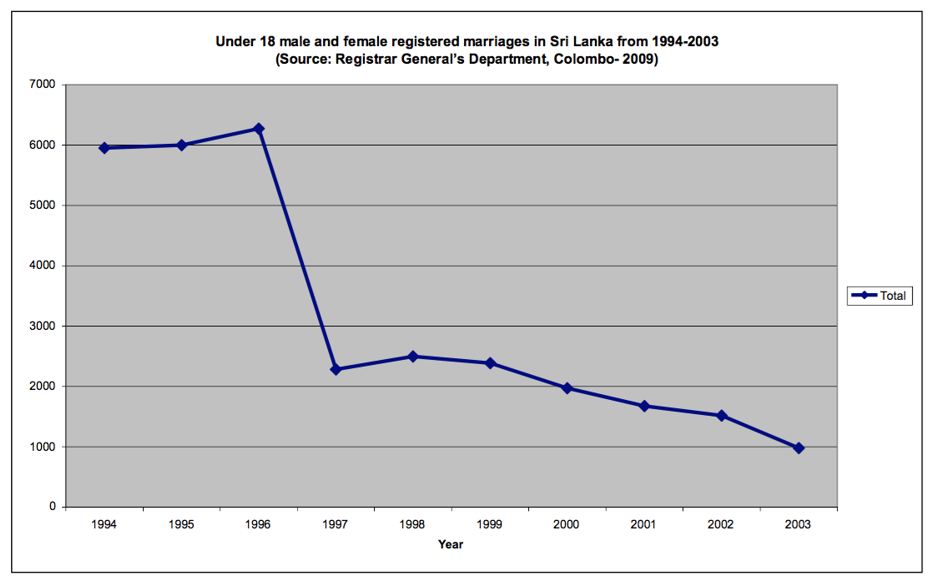

It is important to note here that after the 1995 amendments, there was a significant drop in under-18 marriages in the non-Muslim community.

Noted from Amarasiri de Silva’s research [3] for UNICEF conducted in 2009, the decline was seen among all ethnic groups except Muslims. Data from the Registrar General’s Department further indicated there was actually a percentage increase of Muslim females in under-18 marriages between 1994 and 2003. Recent data on this trend must be obtained with urgency.

According to the research study by Amarasiri de Silva the reason for this increase to 18 years at the time was “on the ground that children younger than 18 were biologically and socially immature to get into wedlock and bear children, and detrimental effects may create problems in children born to such young women”. Progressively, in Sri Lanka the age of majority was set as 18 through an amendment to the Age of Majority Ordinance as far back in 1989 even before Sri Lanka ratified the Child Rights Charter in 1991.

There are other obvious reasons as to why nations such as Sri Lanka feel the need to set standard minimum ages in keeping with modern times. These legal safeguards afford the opportunities for children to complete compulsory education at least up to the secondary level, which to a certain extent would ensure a degree of maturity essential for the responsibilities and consequences of life and marriage. There is also ample research [4] documenting the undeniable impact of child marriage on the rights to education, health, and employment. Early marriages naturally makes girls and women vulnerable to violence and abuse, with limited avenues for recourse due to various reasons ranging from community pressure, dependency, lack of finances and further risk. Early marriage also prevents women and girl’s participation in all spheres of life.

State non-action despite clear evidence of child marriages

There is compelling evidence from women’s organisations working at the community level to indicate that the practice of child marriage is in fact more common than it is admitted to be. According to the ‘Unequal Citizens’ study [5], marriages arranged by guardians are occurring between 14 and 17 years of age in districts like Puttalam and Batticaloa. Records on Muslim marriage registration in Kattankudy indicate that in 2015 – 22% of all registered marriages were with a bride below 18 years of age. This is a considerable increase from 2014 where the figure was recorded at 14%. The practice is also evident in Colombo due to religious and cultural considerations as opposed to poverty and safety concerns as its basis.

The study also points out that according to a Quazi from Colombo East, there are many instances of early marriages happening in areas like Mattakkuliya and Maradana. The Quazi for the minority Muslim community in Colombo also mentioned that girls of the community mostly get married between 15 and 17 years of age because according to him ‘the value of the girl decreases after she is 17’, clear indication of a prevalent patriarchal perception in favor of early marriage.

It is understood that marriages (legal or otherwise) happen due to a number socio-economic and cultural reasons and is prevalent in other communities as well, such as through early co-habitation and pressures of poverty and insecurity. Communities from districts that were affected by the conflict also show an increased number of early co-habitation due to these pressures. But the key difference is that in the Muslim community, it is legal and State has not taken any action in this regard, whereas in other communities the State agencies, social workers and civil society actors are actively working to eliminate the practice in the interest of the children and rightly so.

While the battle is fought within the Muslim community – between affected women supported by community groups, activists as well as a large number of women and men seeking reform, and the conservatives – the State continues to absent itself from these conversations. Up until July 2019, not a single Muslim and very few non-Muslim politicians have come forward publicly on the matter. Nor have agencies like the National Child Protection Authority (NCPA) or the Human Rights Commission (HRC) made any acknowledgement of or desire for action despite it being a child rights and human rights issue. On July 12, MP Faiszer Mustapha announced that Muslim MP’s had unanimously decided on raising the minimum age of marriage to 18 years, among a few other amendments. While a positive sign, until and unless this rhetoric results in comprehensive law reform, they remain empty words.

Standard minimum age of marriage for all citizens

It cannot be stated enough that what is sought in terms of reforms of the MMDA, including raising minimum age of marriage to 18, are basic rights enjoyed by other communities in Sri Lanka. The State is responsible for depriving these rights at the whims of the religious and political leadership of this country. In the current context, it is unlikely that all the stakeholders in the Muslim community in Sri Lanka would agree and reach consensus on matter of minimum age. Therefore State intervention is obligated and long overdue.

Child marriage within the Muslim community needs to be addressed by removing the legal cover that MMDA accords, without exceptions. It is the only way to ensure the minimum age is not decided arbitrarily by Muslim men based on their interpretations and misinterpretations.

It is important for the Sri Lankan state and leaders to recognize and protect the rights of all citizens to enjoy his/her culture, traditions and freedom of religion. Likewise, it is the responsibility of the State to ensure that child rights are not compromised in the name of culture and religion.

Sri Lanka is a party to the Convention on Rights of the Child (CRC) and Convention for Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), among other international human rights instruments, and is thus required to adhere to global benchmarks on child rights and women’s rights. The CRC recognizes anyone under the age of 18 as children and explicitly states in Article 2 that no child can be treated unfairly on any basis including religion, ethnicity or gender. Article 24 (3) of the CRC refers to the obligation of a State Party to “take effective and appropriate measures to abolish traditional practices prejudicial to health.”

If it is the State that sets the provision that all citizens need to be a certain age to be able to make an informed decision to vote, then the very same logic should apply to the minimum age of marriage, which has impactful consequences on the individuals in question, and the country as a whole. If the State determines that adolescents and children marrying before 18 years is detrimental to their health, education and wellbeing then it should apply to all children in the country irrespective of which ethnic or religious group they belong to. Sri Lankan Muslim girls are not born with a ‘special’ reproductive system that makes them ready for marriage at an earlier age.

There is an obvious difference in the treatment of Muslim children by the State itself, which continues to be indifferent to their plight despite being brought to notice by affected women as well as community-based organisations for decades. It is unacceptable that the State itself fails to realise that Muslim girls and boys too are citizens of this country, deserving of equality and fundamental rights as their counterparts. This discrimination against Muslim children of Sri Lanka must end once and for all.

[1} Report of 2009 Committee Appointed to Suggest Amendments to the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act – Vol-1-A https://www.moj.gov.lk/web/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=114&Itemid=230&lang=en

[2] H.Amarasuriya, S. Goonesekera (2013). Emerging Concerns and Cases on Child Marriage in Sri Lanka, UNICEF Sri Lanka

[3] De Silva, Amarasiri (PhD), 2009. Desk Review and Basic Field Data on Child Marriages, Statutory Rape and Underage Sex. UNICEF Sri Lanka

[4] Girls Not Brides www.girlsnotbrides.org

[5] Cegu Isadeen. H, Hamin, H (2016). ‘Unequal Citizens: Muslim women’s struggle for Justice and Equality in Sri Lanka’ https://mplreforms.com/unequal-citizens-study/