Featured image by Selvaraja Rajasegar

Editor’s Note: The following article is a translation of a story by our sister site Maatram.

On October 12th 2018, Maatram filed a Right to Information request with the Labour Department for information on subscription fees for six trade unions that represent plantation workers, requesting the following:

According to the last documents received from the unions by the Labour Department;

- Number of members in each union, and a breakdown by gender

- The membership fee levied from one worker

- Total membership fees obtained by unions in the year 2017

- Total membership fees obtained by unions in September 2018

- Total membership fees obtained by unions in December 2017

- Total amount spent by unions in 2017, and what this amount was spent on

- Total amount spent by unions in 2017 specifically on issues related to tea plantation workers, including but not limited to campaigns, welfare, health and education.

Information of the following six unions was requested;

- CWC – Ceylon Workers’ Congress

- LJEWU – Ceylon National Estate Workers Union

- NUW – National Union for Workers

- UPF – Upcountry People’s Front

- JPTUC – Estate Sector Workers Alliance

- SRFU – Sri Lanka Red Flag Union

Membership fees might seem like an innocuous request to make, but they are significant. The unions represent members who are Malaiyaha Tamil tea estate workers, a community that face significant barriers to accessing essential services such as education. They often struggle to provide their families with nutritious food. These issues tend to come to the forefront during wage negotiations, where the unions act as middlemen between the workers and the Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs).

For years, tea plantation workers have been calling for a an increase in their basic wage to Rs. 1000. A protest held on October 22nd last year at Galle Face Green, mobilised by youth from the Malaiyaha Tamil families who have come to Colombo for work, drew thousands of people. In December, workers began a hunger strike outside the Colombo Fort Railway Station, to make the same demand. Each time, the unions negotiate for an increase, usually amounting to around Rs 50 or Rs. 100. The estate owners say a more significant increase is impossible given factors such as conditions in the global market (including competition) and climate change.

Against this backdrop, the workers view the role of the unions with scepticism. In a recent article by Maatram, titled ‘We don’t know the colour of the union’, tea plantation workers who were interviewed said, “We are giving a membership fee of Rs. 150, to speak on behalf of us whenever we have problems. But we have not received any help so far. They also commented on the actions of the union leaders, “They are living on the membership fee we give. They are living luxuriously.”

After Maatram handed over the original RTI application on October 12, 2018, it took exactly two months for the Labour Department to respond with the information requested in the application. The Information Officer said that the acknowledgement could not be given immediately, as he did not know Tamil. Maatram received the receipt of acknowledgement on October 25, and this was within the response time period stipulated in the RTI Act (2 weeks). Editor Selvaraja Rajasegar has previously spoken to Groundviews at length on the difficulties in place for individuals requesting information from government offices in Tamil in this video.

Only questions No. 1 through No. 3 raised by Maatram were answered in the response that was received on December 12th. The Labour Department stated that the information pertaining to the other four questions was not with them.

Maatram was compelled to contact the Information Officer over the telephone as the response was delayed by two months. “Since the people here do not know Tamil, your application has to be translated to Sinhala or English. The entire department has only one translator. We all give it to him/her, that is why there is a delay,” was the Information Officer’s explanation.

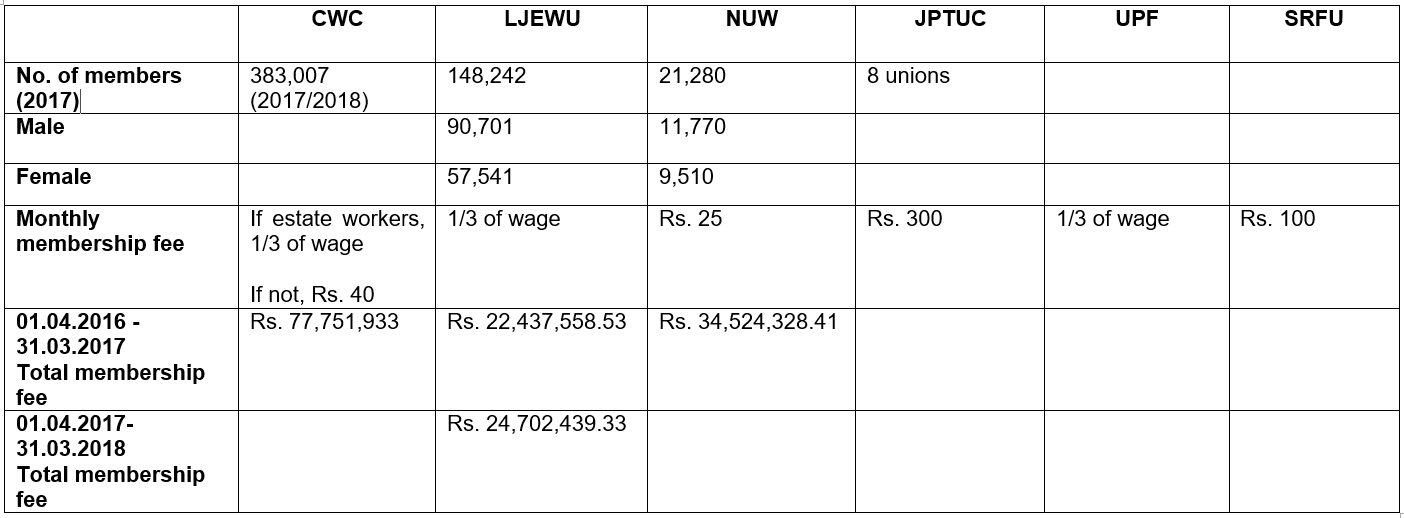

Maatram was able to obtain information around the members of the worker unions, the membership fees levied from a single worker, and the total amount in membership fees obtained in one year by these unions.

The blank spaces indicate information that the Labour Department does not have.

The blank spaces indicate information that the Labour Department does not have.

What the information reveals

Maatram requested information based on the most recent documents that the Labour Department had received from the six unions. The information that the Department provided was based on reports from 2017.

According to these documents, the Ceylon Workers Congress has a membership of 400,000. The Ceylon National Estate Workers Union has 150,000 members while National Union for Workers has 21,280 members.

It has been reported that the total number of workers in the estate sector has fallen to 150,000, however the total number of members in these three unions alone surpass 550,000. It is evident therefore that while the unions possibly submit outdated details to the Labour Department, the Department inputs these records unquestioningly, without carrying out any formal follow-up of its own.

According to the details received, in the one-year period between April 1st 2016 and March 30th 2017, the Ceylon Workers’ Congress received Rs. 77,751,933 as membership fees from workers. Likewise, the Ceylon National Estate Workers Union received Rs. 22,437,558.53 while the National Union for Workers received Rs. 34, 524, 328.41 through membership fees.

Maatram appealed to the Labour Department for answers to questions No. 4 through No. 7 (which had not been provided in the first response) and for the annual reports of the unions. The Department responded stating that the reports cannot be provided according to Clause 5(1) f of the Right to Information Act. The clause lays out a criteria for the denial of access to information;

5(1) Subject to the provisions of subsection (2) a request under this Act for access to information shall be refused, where–

- This clause lays out a condition for refusal, the information consist of any communication, between a professional and a public authority to whom such professional provides services, which is not permitted to be disclosed under any written law, including any communication between the Attorney General or any officer assisting the Attorney General in the performance of his duties and a public authority;

Maatram has appealed this decision before the Right to Information Commission.

Click here to view the first response by the Labour Department. Click here to view the response upon appeal.