Sharmini Pereira: What’s your earliest recollection of wanting to study art? Was it something that you were encouraged to do or something that you encouraged your family to allow you to do?

T. Shanaathanan: I come from an orthodox middle class family and my parents have some interest in art. I learnt the basic principles of art form my mother through her interior designs, embroidery, flower arrangements and gardening. As many children do, I too enjoyed drawing and image making in various materials. When I joined St Johns College my class teacher Mrs.Yogarajah was the one who first identified my talent and encouraged me. From that time I started closely identifying myself with the word ‘art’ and my parents started supporting me. My father used to buy children books published in China and Russia because of their illustrations. Although I rarely read them, I enjoyed looking and copying their illustrations. I also enjoyed all my art and handwork classes more than other subjects in my primary school. When I moved to middle school the art room became the main source of inspiration because my art teacher Mr. N. Thevarajah permanently exhibited students’ work that he considered great. These works further fueled my interest. At the age of twelve, my family went on a pilgrimage to India and my father was very keen to show us all the culturally important sites and museums. When we were in Calcutta Museum I saw art college students coping medieval sculptures on display. I still remember that I was more thrilled by looking at their drawings than the original sculptures.

During the 1980s a South Indian traditional sculptor named Pannirselvam was stationed in my neighborhood to build temple towers (Kopuram) for our village temple as well as temples in the surrounding areas. I had a chance to watch him at work. When I started going deeper into art my parents worried about my studies. They viewed art as a hobby but not as a profession. Like many middle class parents they persuaded me to study biology to become a doctor, by saying my skills in drawing will make biology easy.

SP: Aspects of biological drawing do appear across many of your paintings and drawings from an early stage. Did you study biological drawing?

TS: When I took the biology stream for my advance level I could not fully concentrate on my studies for two reasons. One was the presence of the Indian Army (IPKF) in Jaffna, the JVP insurgency and the counter insurgency, which was at its peak in the southern part of the country. In 1987 my house was burnt down by the IPKF, which was an event that traumatized my family with the direct experience of violence and displacement. The other was my engagement with art led me to connect with other young artists and led to the preparation of a solo exhibition.

SP: A growing community of intellectuals, artists and cultural activists began to return to Jaffna after 1983. What was your relationship with them?

TS: In the aftermath of the riots against the Tamils in southern Sri Lanka in 1983, many of the Tamil speaking intellectuals, artists and writers moved back to Jaffna. The armed struggle to achieve the aspirations of the Tamil people was also reflected in the cultural sphere. Theater and literature were radicalized by the suppressed voices. This quickly had an influence on the visual artists. Many young artists began to have higher ambitions of being an artist without commercial interest. Few of the school art teachers recognized these youngsters purely because of their radical approach to art. During the time a chain of exhibitions happened in Jaffna town. Most of the militant groups during the 80s smuggled arms from south Indian but also serious publications. Through these routes images of Indian modernism reached Jaffna in the form of monographs and reproductions published by the Lalit Kala Akademi and book illustrations. The revitalization of the visual art scene by young painters and the respect I started to acquire for artists as intellectuals and reformists transformed my interest in art and led me to become an artist.

SP: What kind of art was being made during this time that you saw? Can you describe it and talk more about where it was being exhibited?

TS: During this time Tamil nationalism was gaining visual presence. There was a lot of discussion about the representation of Tamil identity or how to build up an artistic identity for Jaffna Tamils. On the other hand the valorization of illusionistic techniques continued with the acceptance of modernist distortions and abstractions because these languages were seen as different. The realties of war started to gain visual presence and in doing so challenged the traditional notion of painting as something beautiful. Pain, distress, disappearances, loss and destruction became popular themes alongside freedom and revolution. Most of this work was being exhibited at schools and the University, as there were no art galleries. I was due to exhibit in 1987 but couldn’t because all of my works got damaged when our house was destroyed by the IPKF. I had my first solo show in Jaffna in 1989 at the Vembady Girls’ School.

SP: Did you see your work as part of a continuum of what was going on or did you feel you needed to critique or move away from it?

TS: If I revisit my paintings of that period they represent an odd mixture of styles influenced by illustrations from popular magazines and calendar art. And their content varied from mythology to literature, landscape to oriental lifestyle and modernist styled works. But the human figure occupied the central space. I wasn’t able to represent the socio political situation in my works because of my typical middle class upbringing and was not able to handle modernist languages due to lack of exposure. Without this content in my work I was not able to attract attention from the so-called radicals. On the other hand since my vocabulary and imagery were familiar to the common man, others encouraged me.

SP: What led you study in India? Was it because of the influence of the books and journals that were smuggled into Jaffna from south? India?

TS: At that time the only option to study visual art in the whole country was at the Institute of Aesthetic Studies in Colombo. Since its medium of instruction was in Sinhala I had to go to India. When I was about to move to India for my higher studies the political situation in Jaffna and in the region was worsening. Jaffna came under the control of the LTTE and the Sri Lankan government imposed an economic embargo on the north and its military actions involved constant air raids. So there was a shortage for medicines, fuel, food items and no electricity. There was no direct land route to Colombo. The affluent strata of Jaffna society started fleeing the peninsular. Initially my aim was to join the Madras College of Art but the assassination of then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi tarnished that venture and put back my efforts to study art for a further two years. With great struggle and the help of many people I somehow managed to enter the Delhi College of Art in 1993.

SP: When you eventually reached India to study did you feel like you were part of a community or were you treated like a stranger?

TS: Since I was familiar with the Indian art scene through different publications I felt like a local in India. Before joining the Delhi Art College I had to spend six months in Madras. During that time I had a chance to visit many of the prominent artists’ studios in Madras. Their interactions and their working environment gave me a lot of strength in the struggles that lay ahead for me. During that time I interviewed more than ten eminent artists and published the texts in Sri Lankan Tamil daily newspapers. The exercise helped me to understand the process of art making as well as art history. Actually many of these artists appreciated my skills in writing in Tamil. One of the most celebrated south India artists the late Mr. K.M. Adimoolam invited me to contribute a Tamil text on his practice for a glossy publication on his artistic career called In-between the lines. I was in my fourth year of my Bachelor degree at the time and still consider this as a great honor.

SP: While you were in Delhi doing your MFA did you ever think that you would return there after you graduated to complete your PhD?

TS: Although I got a placement in Australia to do my Masters after my BFA I decided to come back to Jaffna during the curfews, abductions and bomb blasts for two reasons. First of all my parents were living in Jaffna with the great hope of change. My father in particular refused to move out of Jaffna and encouraged me to come and be here. Second I love to work and live here because this place holds something special for me. My interest in being an artist is not just about achieving professional gains such as selling work, showing in international exhibitions and appearing in glossy catalogs, it’s about where I am located. I love to be with my people, I love to work in my own surroundings. In this context the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Jaffna offered me a lecturer position in art history. Teaching art history for nearly eight months awakened me to the importance of doing a masters course and the possibilities of art related work in Jaffna. For these reasons I went back to Delhi for my masters. My masters degree brought a passion to do research. During that time I had the opportunity to meet many young researchers from all over the world since I was living in close proximity to Jawaharlal Nehru University. At that time JNU had not yet established its School of Art and Aesthetics. I came back to Jaffna and got a permanent position in Jaffna University. After working there for nearly seven years, I joined Jawaharlal Nehru University to do my PhD research on class, identity and visual Art in Colonial Colombo, which I completed in 2011.

SP: In total you spent ten years in India during a time when many important changes were taking place within the contemporary art scene there such as the success of artists like Subodh Gupta, Nalini Malani, Jitish Kallat and Atul Dodiya; the emergence and boom of the Indian art market and the opening of several notable commercial galleries like Vadhera, Gallery Skye, Bose Pacia, Nature Morte and Talwar Gallery. When the School of Art and Aesthetics opened in 2004 it also adopted a multidisciplinary approach, drawing on insights from the fields of anthropology, history, media and cultural studies where students were introduced to a range of research methods that combine archival, ethnographic, theoretical and cultural approaches. What kind of impact did all this have on you, given what was going on in Sri Lanka politically and culturally?

TS: Yes when I joined Delhi College of Art there were very few commercial galleries but when I went back for my PhD in 2007 there were more than a hundred private galleries. There was also a major shift in the life style of several contemporary artists whose works were attracting huge prices. A few of my batch mates were some of those who began to do well commercially. Initially I was so confused by the art market and the changing social position of the artist with their newfound wealth. I really felt that I missed the bus by being in Sri Lanka. But on the other hand new discourses around art of the time drastically changed the way in which one looked at artistic merit and achievement. That helped me to realize my position as well as my mode of art practice.

SP: Though JNU is a politically aware campus was it an environment where teachers and other students were actually aware of the political situation from where you had come? Or did you find yourself working in isolation without an opportunity to discuss ideas that were part of your context and concerns? What kind of impact did being away from your family and the worsening situation in Sri Lanka have on your work?

TS: JNU is a politically active space and most of them knew about the Sri Lankan situation taking different opinions and multiple standpoints. Some groups at the university were openly critical of the Indian and Sri Lankan governments for their war campaign and supported the Tamil cause. But the realities of my home front always pushed me to maintain a distance from the activism going on around me. But my stay in JNU did shape my theoretical understanding of political as well as artistic identity. By contrast my Delhi College of Art days were formative years in terms of my practice today. Unlike JNU, the College of Art community didn’t know much about the Sri Lanka conflict. Many of them did not understand the nuances of my existence in Delhi and the anxieties I was living with. I did not even try to open myself to anyone there. I was also not interested in directly showcasing any of my agonies or discussing them. Furthermore I had a strong feeling that I was under the surveillance of the Indian intelligence due to my Jaffna Tamil identity.

SP: When the Jaffna Exodus took place in 1995 how did news reach you in Delhi?

TS: When the exodus of Jaffna happened in 1995 I did not know what had happened to my family and house. I spent nearly two months without knowing whether they were alive or not. Meanwhile I had to attend classes and pretend to be normal. During that time I went through an existential crisis and my paintings became more and more personal.

SP: ‘Pretending to be normal’ expresses something so basic yet so fundamentally debilitating. Not being part of the ‘norm’ is a condition that many in the country find themselves. While having to ‘pretend’ compounds this feeling of isolation from the mainstream or majority it also introduces the idea of the mimetic impulse, a term used by anthropologist Michael Taussig. Taussig posits that ‘The wonder of mimesis lies in the copy drawing on the character and power of the original, to the point whereby the representation may even assume that character and that power.” (Taussig, Michael. Mimesis and Alterity. New York: Routledge, 1993, xiii). To what extent have you had to pretend to be what you are not as a means to assume authority or agency?

TS: This was not the first time I had to pretend. In Sri Lanka being a Tamil means being a stranger or a suspect. We have to prove ourselves to the state and its machineries through a series of pretentions. This pretending helps me survive on a day-to-day basis. It is a situation that led me to evolve a metaphorical or symbolic language in painting. I started self-interpreting Hindu and Christian mythology. In a way my paintings created my personal myths, or an attempt at empathising with my own self. This metaphorical language gave me a safe passage to enter the Colombo art scene during the peak time of the conflict without misrepresenting what I felt.

SP: I vividly remember reading the title of a conference paper that you gave for the 2008 Tamil Studies Conference called ‘A Stranger and a Suspect – Being Sri Lankan Tamil: Narratives of Personhood in Visual Art’ and thinking how the role of narrative changes when the person doing the telling is regarded with suspicion. We are accustomed to believe not question the narrator. Who was your audience?

TS: I started telling my stories to my canvas. Through which my content and approach changed. I began finding new meaning in the urge to paint. This was the time I also moved away from the typical mindset of the middle class and the conventional ideas of beauty. I painted nudes, gory pictures and grotesque bodies. People said I had a big box inside my stomach.

SP: Most of your figures at this stage are faceless or have their faces hidden. It’s difficult not to read them as self-portraits but its also tempting to see them as symbols of human suffering as a result of the conflict. Were you concerned about turning yourself into a victim or worried that your work was taking the suffering of a community as its subject, which is sometimes typical of a middle class outlook?

TS: I do not disconnect my self from my community but those paintings are about victimhood. As I said before in the 1980s the artist was considered a rebel but the situation changed in the 1990s when the LTTE proclaimed that they were the sole representatives of all Sri Lankan Tamils. With that their cultural wing and the artists who worked with them became the official body. You were either with or against them, which made me feel like a double victim. Although I empathized with society’s suffering as my suffering I did not have agency to claim it because of the hegemony of the LTTE. At one point I felt that the language of painting that evolved from the feeling of nostalgia was not sufficient enough to talk about violence in this country. Since the portrait represents the personhood, removing that in my work represented an identity-less-ness. But this wasn’t enough for me, so I chopped off the head of the figure. In the absence of the head or the face how could one express feeling? I used the structure and the posture of the body to convey feeling. The figure in this sense became the main site of inquiry in my works. In many cases my own body became the point of reference. Looking back I can now see them as autobiographical.

SP: In 1994 you made Missing. It shows a wailing dog seated next to a pair of rubber slippers. The mood is one of anguish and desperation yet no figure is present. Were you conscious of removing the figure completely?

TS: I did this work as a response to the human disappearances that became routine in 1987. This was the going on around me. I was more conscious about the particular mood of the work rather than the removal of the figure. I did this work just before I started engaging with the human figure on a more conceptual level.

SP: I want to ask you about a work you did in 1995. This work was made in response to a poem by P. Ahilan, who in turn wrote the poem in response to a painting called Bunker by Nilanthan. The way these works came into being suggests you were part of a collective conscious. How often did you discuss the situation amongst one another? Or was this a subject that went unspoken?

TS: Well Ahilan and I often discuss our work and exchange views. At that time I was reading Tamil poetry as a means of contemplation. The etching I made was simply titled Jaffna and was more or less a literal translation of Ahilan’s poem called ‘Bunker days’. Other than this I have not made work that has involved a similar process.

SP: How about in 2008 when you were working on The One Year Drawing Project, which involved responding to drawings by Jagath Weerasinghe, Chandraguptha Thenuwara or Muhanned Cader? What kind of influence did this process have on your work?

TS: Although my works are mainly situated in the domain of drawing, I did not realize this until I got the invitation to work with an entirely drawing based project, collaborating with established artists who were each known for their strong lines. The playfulness involved in the process made me approach the medium more freely and spontaneously than before. It also helped me to expand my stock of visual vocabulary.

SP: In 2003 you made a work called Dislocation. What’s interesting about this painting is the frame of the work has cut off the head of the figure. The remaining figure stills remains faceless and without identity but the intervention with the frame seems to introduce another kind of removal or ‘dislocation’ of the figure. The contorted body engulfed by turmoil of previous works has also been replaced with an imposing four-armed figure. The landscape, or the idea of landscape, also takes on a presence that is different from previous works. Was there anything behind these shifts that you were conscious of at the time?

TS: The Norwegian mediated peace talks between 2002 and 2007 exposed some important realities for me. Firstly the peace talks permitted a certain amount of free movement between towns and cites. When you travelled, both sides of the roads particularly in the border areas you saw danger signs indicating the presence of land mines. This was shocking and depressing to see and raised questions in my mind about the future of the land even after achieving so called peace. Secondly, when I travelled between Colombo and Jaffna by air, I came across the Tamil diasporas children and grand children visiting their grant parents. In their long waited homecomings, the grand children could not converse with their grand parents because they spoke different languages than Tamil or English. Even first cousins coming from different countries could not converse because they spoke different languages. Although they all belonged to one family they all had different passports and citizenships. Thirdly due to the creation of the high security zones many old villages simply disappeared. The only trace of them was to be found on maps. These three realities pushed me to work with landscape in the form of maps.

SP: One of the key works from this period was connected to the ancestral home of your grandmother. Can you talk more about this work?

TS: Initially I reinvented my school map-making lessons for this purpose and later I made maps from my memory. In my painting My grand ma’s courtyard II, I recreated through memory the surroundings of my grandma’s courtyard that was erased by several bombardments. To introduce the notion of time I collaged, stitched, layered, superimposed and juxtaposed maps of different styles onto the work.

SP: In your writing you’ve described the dislocation of people from Jaffna as a ‘collaged community’ (Pathways of Dissent: Tamil Nationalism in Sri Lanka, Sage Publications, 2010). The description is apt for thinking about the fragmentation caused by the conflict but in the idea of collage there is also the possibility for re-grouping. In art, collage is based on the premise of creating a new whole from unrelated parts. Often the parts are found objects (newspaper cuttings, photographs etc). Your description of a ‘collaged community’ prompts a further illumination, namely seeing the dislocated community as a grouping of found objects. It’s an evocative metaphor in what it suggests about the condition of being displaced. In your work History of Histories such an idea seems to be explored to the full. What role does collage play in your work?

TS: For me the act of collage is not a technique but it is associated with the very meaning itself. The whole act has a personal as well as a collective meaning to me. As you mention it became an ideal vehicle to convey the nature of the community and the reality I am living with and for talking about a possibility of re-grouping. A re-grouping based on the acceptance of identity as fragmented. So it works against all the meta-narratives of identity. In History of Histories the act of collage or random association of an object was an attempt to take the individual loss or pain onto the level of a collective. On the other hand it also represents the co-existence of difference and simultaneity of mismatching realities.

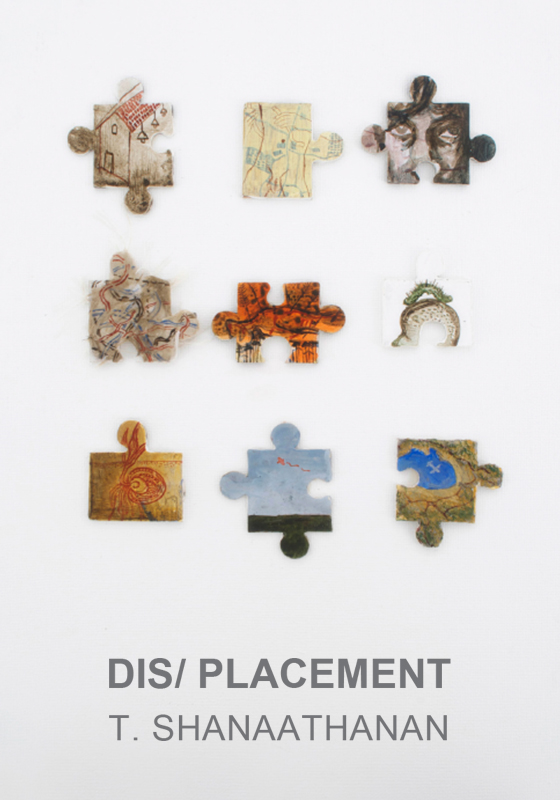

SP: The jigsaw first appeared in your work in 2003 as part of the painting Dislocation. In 2012 it defined the shape of the canvas and you painted large jigsaw pieces in the 9-part work Mismatches. In your latest body of work many jigsaw shaped paintings are carefully grouped together, in a display similar to the way scientific specimens or a collection of butterflies might be viewed. What prompted you to use the jigsaw and how did it evolve from an element that was initially placed within your painting to one that now contains your paintings?

TS: Jigsaw pieces first appeared in 2003 as parts of my paintings, where I placed a jigsaw landscape against the bodyscape and a jig sawed body against the unified landscape. I was trying to look at the tension or the understanding of impossibility of an identity based on unified territory, nationality, citizenship, linear history, purity of race, language and so on. Later in my artist book project The Incomplete Thombu, which maps the experience of displacement by exploring the physical and emotional boundaries of home through the act of drawing, an image of a jigsaw appears as my response to the last story that talks about the experience of resettlement. In that story the person talks about the experience of being a stranger in her own street due to the change in the neighborhood and the scattering of the community. This story became the starting point for my exhibition in 2012 Mismatches. Here I made nine separate individual pieces of jigsaw that represent different memories, incidents and experiences and exhibited them together as Navagragam (nine planets).

SP: In your new work the scale has changed. Was there a reason for this?

TS: Yes, because I felt although I changed the format of the painting, the size did not allow me to explore the possibility of working with the jigsaw shaped surface. By using smaller pieces I can concentrate on minute details and the image becomes more abstract. Hence this format allowed me to concentrate on tiny areas or little corners and intricacies of experience. The small size also literally attracted me to depicting small things. As an artist this also gave me a fresh challenge to work out of my comfort zone by pushing me to do miniature like brush drawing.

SP: In addition to the change in scale these works are grouped together. Did the smaller scale contribute to this?

TS: After I had my 2012 exhibition I felt that the 9 single pieces were not going far enough. That’s how I came to the groping of jigsaw pieces in a single work. These jigsaws became specimens of what has been lost and preserved in memory. The idea of the specimen interested me and led me to look at the display methods used by natural history, archeology and geography. I found the insect boxes in the natural history museum fascinating and thought about my idea of specimens as occupying a similar kind of space. So I randomly arranged uneven shapes of jigsaws along a grid to produce a tension between ordered and disordered elements. In this arrangement the design of the negative space or the background emerged as a new space. What is the meaning of this new space? Is it merely the background or a meeting place? Is it a place of impossibility or recreation?

SP: By breaking the rectangular form of the canvas you are also subverting the traditional view of landscape which has historically sought to ‘frame’ a view or scene, giving rise to what we know today as the picturesque. This rupture of the frame is also there in the work of Muhanned Cader who dispenses with the rectangle in favor of curved edges. The effect of doing this is unsettling for the viewer because they are accustomed to seeing an image in a rectangular or square format. Was this your intention?

TS: My basic intention was not to subvert the traditional format of the painting but my conceptual engagement in the last ten years has slowly taken me towards using a picture plane that has uneven edges. I am just following the painting and reacting to its process. So I do not exactly know how it is going to go. But after making nearly two hundred jigsaw pieces for this exhibition, I have the urge to make more. Although each piece of jigsaw does not have a rectangular edge they all are placed within or presented within a rectangular frame and are meant to be seen together. Their random association is very crucial to their meaning. The imagery in the jigsaws is not limited to the idea of landscape but includes memory, history, mythology and the body.

SP: Can you say something about the imagery that you have painted especially in relation to some of the different styles of painting in this work?

TS: I consciously used different styles and approaches to bring out a tension. The styles also vary with the experience or the object they are referring to. For example to talk about the historical as well as mythical time I painted portions from old temple murals. Similarly I used parts of group and individual photographs to depict the idea of memory, loss, and people. Other visuals are drawn from maps, objects, scenes, landscapes, human anatomy, events, myths, legends and decorative motifs. Since the approach to the visuals varies from iconic to symbolic to indexical, the meaning changes accordingly.

SP: The different styles also evoke the idea of different ‘hands’. This is something that has appeared in several other works by you, such as History of Histories (2004), The Imag(in)ing home (2009) and The Incomplete Thombu (2011). Only this time your own hand is the one articulating the differences. I like the tension this creates with the other works. Is this something that you have thought about?

TS: In History of Histories, when I first arranged the objects belonging to different individuals I was never aware of this tension. But I felt it immediately after seeing the installation and that made me think about the association of objects rather than the single objects. In The Incomplete Thompu book project my task was to respond to the diverse stories of completely different individuals. Hence the stories demanded a different kind of articulation; that reshaped my own drawing practice because the stories were not fully mine. This experience led me to make work in this form using a variety of styles. It is like telling my own story in other’s voices that refer to difference times, places and memories, using a collage of painting styles.

SP: The assemblages of jigsaw pieces remain unconnected and held in place by the grids you have arranged them in. It’s as if things are hanging in abeyance or in a state of anticipation.

TS: Yes you are right, unfortunately these works talk about an uncertainty. I see each of these pieces being connected to the realities outside the picture frame. What we realize now is that the end of war does not mean the end of the conflict. It is another war in disguise or in a different form. Here the enemy is not visible. The so-called post war is more harmful than the war. The fragmentation that started with the ethnic conflict has never been allowed to settle and the post war period has in effect encouraged further fragmentations. The situation right now is one of uncertainty. We live in interesting times.