Photo courtesy of Daily News

My Lunches with Orson is the title of a collection of interviews that Henry Jaglom, a US avant-garde filmmaker, did with Orson Welles over a period of two years (1983-1985). It is at once insightful, refreshing, provocative and compelling, and it shows Welles at his best. At the time Jaglom was more than 10 years into his own career; he had tried his best to stage a comeback for Welles and failed. The book reveals Jaglom’s admiration for Welles and the colossus that Welles, despite his rambunctious personality, was.

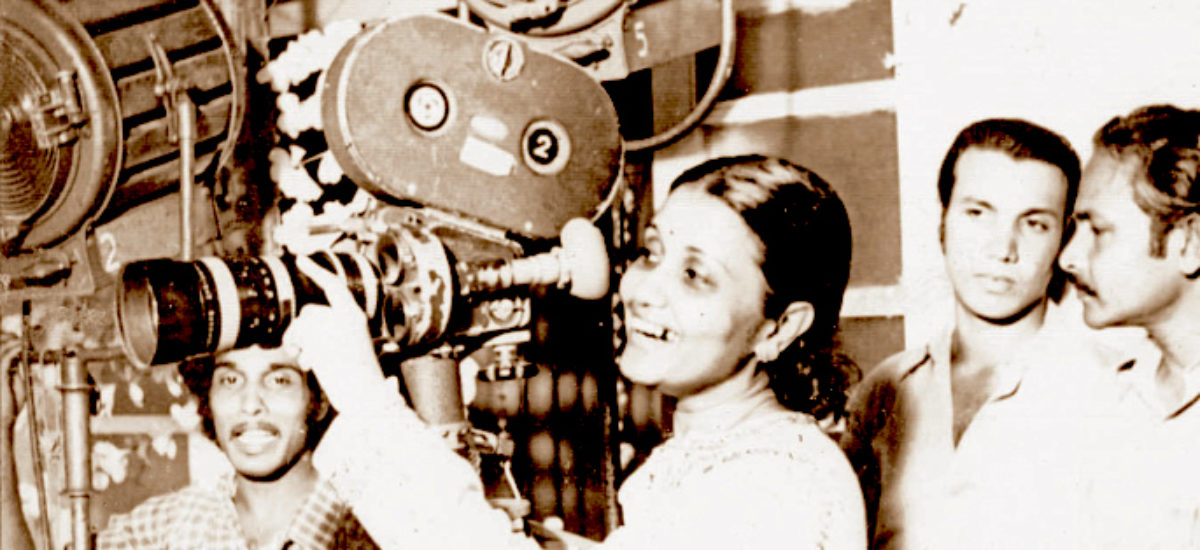

Re-reading Jaglom’s book the other day, I suddenly remembered Sumitra Peries. Peries passed away last Thursday. That morning, I received a call from a friend of hers telling me that she had been admitted to hospital owing to a stomach ailment. An hour later they announced her death. It was just too sudden, shocking and saddening.

I sat down, pondering the many conversations we had shared at her place, processing the fact that there would be no sequel to them. I thought back on her career and her legacy. Put simply, it seemed as hard for me to see the full stop in the mirror, as it would have been for Kusum at the end of Gehenu Lamayi (1978), to see the question mark in hers.

“The end of an era,” a mentor of mine, a distant relative of hers, messaged from Toronto. A convenient cliché but in this case, a most suitable summing up.

For Sumitra Peries was not just a symbol of some golden and bygone era; she was its last emissary, its last survivor, its last face. Her husband epitomised that period no less; his passing away five years ago signified the beginning of a transition. With Sumitra’s passing, that transition is now complete. The question is, what do we make of it?

Sumitra was not just a director, an editor or an assistant, although she wore these titles in her life. She was also an indefatigable connoisseur and a gadfly who happened to dislike the process of writing and speaking. She hardly wrote to the press and was reluctant to talk in front of a crowd. “I don’t want to,” she once told me. “I simply can’t get myself to do it,” she quipped on another occasion. As such, we lack the anthologies, the essays, the reviews, the reflections, which her husband had and got published in his lifetime.

In other words, we lack material for a memoir or a biography. This should force us to engage with her legacy as one of our last great icons, those who hailed from the colonial period and saw through some of this country’s most pivotal social transformations.

Her life and career have been charted many times before by many writers. By themselves, they constitute the stuff of films: hailing from a rural upper middle class; born to a socialist and radical political heritage from her father’s and uncles’ side; displaying a rebellious streak as a teenager and a young adult; travelling solo to meet her brother in Malta before even turning 21; and living on her own in Lausanne and Paris before suddenly whisking herself off to Brixton in London. In all this, she remained a woman ahead of her time, daring enough to explore her frontiers but also pragmatic enough to know how far she could reach out and when she had to retreat. Eventually, she returned to her place of birth and sought work as an editor on her husband’s films, soon carving her own path.

In all this, Sumitra tends to be framed as Lester James Peries’s significant other, which she was, to a certain extent. Her work as editor on Lester’s films on the best he ever made from Gamperaliya (1963) to Golu Hadawatha (1969), as well as his masterpiece, Nidhanaya (1970) helped her grasp an art form she had studied in England.

Yet such a reading of her life reduces her to a mere adjunct, an appendage whose only function was to sustain her husband’s work. To understand Sumitra’s contribution to the cinema we thus need to go beyond this framing of her and instead critically reflect on her relationship with Lester and the world he opened her up to. To do so, we need to invert the conventional reading of her; we need to chart the world she opened him up to.

Sumitra was linked through her husband to some of the most exciting strides in the arts and culture that were making themselves felt in post-independence Sri Lanka, and not only in film. Lester James Peries’s brother, Ivan (1921-1988), had been one of the leading figures of the ’43 Group, which challenged establishment circles and sought a modernist revolution in the arts. Born to largely middle class and Westernised milieux, the ’43 Group laid the seeds of the cultural revolution that was to flow years later after 1956. Not everyone in the group shared the political convictions and the nationalist ideals that made 1956 possible but even if they didn’t share them, they still considered them inevitable.

Despite the enthusiasm of its founders, however, the ’43 Group was not without its flaws and limitations. “The verve and the enthusiasm of the forties,” Ian Goonetileke observed many decades later, “petered out, perhaps because they were insufficiently grounded in the bedrock of the cultural patterns of Sri Lanka.” Goonetileke noted the fatal paradox which underlay, and undergirded, Sri Lanka’s most promising avant-garde movement – its lack of familiarity with the very culture it sought inspiration from. “I wasn’t rooted in my culture,” Lester Peries once admitted to me. In part, this was due to his Westernised and Christian upbringing. “We were actively forbidden to look into or be interested in other cultures.” To be intrigued by the latter was to invite punishment. “Going to a Buddhist funeral was out of the question. You had to pay penance if you did such a thing.”

These limitations crippled most of the other members of the ’43 Group and many of those who followed it as well. To be sure, Lester’s maiden work, Rekava (1956), significantly broke with all the conventions and formulae of the Sinhala film. However, we need to place such achievements in their context. In her biography of Sumitra Peries, Vilasnee Tampoe-Hautin says that “all Sinhala-speaking films were born in South India.” Born, bred and buttered in the Madras studio, the Sinhala cinema therefore remained an enigmatic paradox. With his Westernised ethos, Lester may have found this state of affairs too infuriating to tolerate. As he was fond of saying, the Indian film was “neither Indian nor film.”

However, while challenging what I like to term the South Indian orientation of Sri Lankan films, Rekava was in later years castigated by those who felt that its view of peasant life in a Sinhalese village was too artificial, too contrived. While Lester and his cast and crew had indeed departed from the patterns of the conventional Sinhala film, many if not most of them were not grounded properly in the culture they sought to depict in it. They wanted to be true to life, but their very backgrounds constrained them.

In other words, while they had ruptured the South Indian domination of Sri Lankan cinema, they were unable to bypass their personal limitations. This was as true of Rekava as it was of the’43 Group and of the cultural elites that had moulded it.

Much of this intelligentsia thus failed to make the proverbial leap. Many, like Lester’s own brother, emigrated to fairer climes; others, like Justin Deraniyagala, retreated to a world of their own. A few managed to question their intellectual inheritance and go beyond. Among them, the most prominent would be George Keyt (1901-1993). In Keyt’s case, however, his childhood interest in Buddhism and his marriage to a Sinhalese and later an Indian Muslim pushed him away from his Anglicised, middle class background. I think that was the key to Keyt’s evolution; in effect, his marriage to those far more rooted in their society helped him defy his limitations. That proved to be no less useful to Lester. This is where we should place Sumitra and her contribution to the cinema and to her husband’s work.

Hailing from a staunchly traditional, yet politically radical family, Sumitra represented at every level the antithesis of Lester’s upbringing. Speaking at a function nearly 10 years ago, Sunil Ariyaratne rather flippantly outlined the differences: Catholic/Buddhist, city/village, conservative/socialist, UNP/LSSP. These contradictions did not split the two of them apart; rather they brought them together and welded the one to the other.

Sumitra’s enduring contribution to her husband’s career, which critics who perceive her as a mere appendage to his work fail to note, was hence to turn him away from his inheritance and bring him closer to a culture he so desperately wished to depict. In doing so, she helped Lester transcend the limitations that the other members of the ’43 Group, to which he belonged by proxy, could not. Through that the two of them managed to bring about the revolution of the arts that 1956 had so tantalisingly heralded.

There is certainly no doubt that Sumitra Peries will be missed. She did much more than what critics and journalists concede and her contributions are more vast than we give her credit for. In the absence of any written or even oral evidence from her side, however, it behoves us to explore and assess what she did and put it to paper. I believe this is the task of the intrepid historian, critic, journalist and biographer. Such an endeavour is urgently needed now at a time when, quoting that Gramscian quip, the old world is dying and the new struggles to be born. Sumitra’s death symbolises a passing and a transition. One only hopes that we do not forget her legacy and, more importantly, what we should do about it.