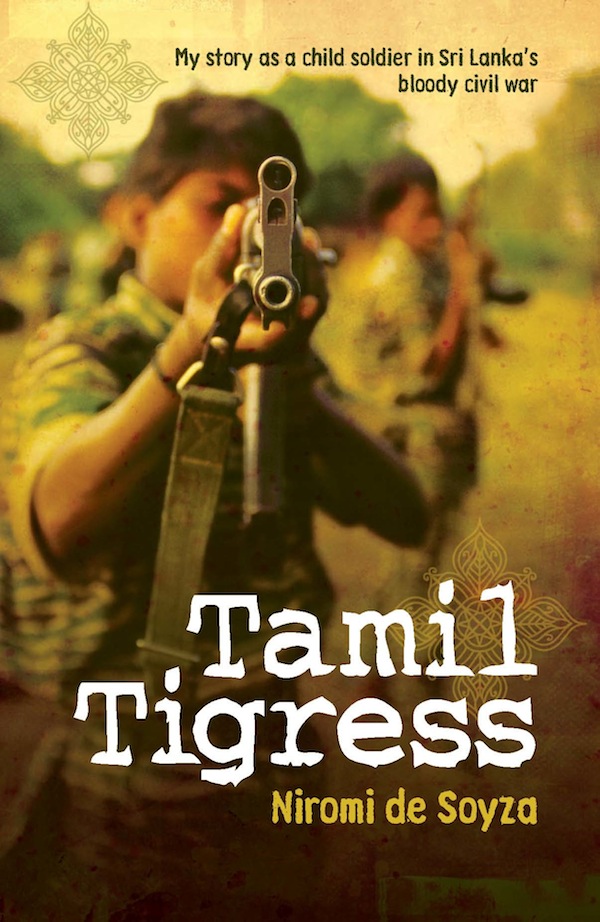

Niromi de Soyza’s so-called autobiography, Tamil Tigress, has received extensive coverage in Australia and has traversed the world now because of critical reviews by several personnel and devoted defence from others. It has been described as “part memoir, part compelling reportage, part mea culpa” by Nikki Barrowclough in the Sydney Morning Herald’s weekend magazine.[i] Gordon Weiss, the moral crusader, proclaimed it to be “incredibly moving” and considers it “a story of redemption” (as quoted by Nikki Barrowclough). This may well be one of the motifs that Robert Perinpanayagam, a perceptive commentator, sees as the potential crux of the book in his unelaborated blog comments.

Without denying that dimension of the book if one stretches a point and treats it as a “faction,” that is, a “fictional narrative based on real events,” rather than a historical account, its self-presentation as a memoir[ii] and “true story” renders Tamil Tigress liable at the same time to the charge of deception (a combination stressed in my little-noticed third article on the topic[iii]). Indeed, it is arguable that it could be subject to a legal charge for a misleading advertisement that deceives consumers.[iv]

My initial doubts arose from the back cover advertisement that stated that young Niromi’s platoon found itself under attack from “government forces” during the Christmas season of 1987, a central emphasis because the book was structured to begin with this dramatic account of an “Ambush” in Chapter One. Anyone familiar with Sri Lankan politics over time would be aware that the Sri Lankan army was confined to barracks in August 1987-89 and that the LTTE had been engaged in ground warfare of a guerrilla character against the Indian troops of the IPKF from October 1987.[v] However, most Western readers and new generations of Sri Lankans and/or Lankan migrants may not have been cognizant of this fact. Hence the whiff of deception together with my early doubts as to whether Niromi de Soyza had fought at all.

My reading of the book led me to the conjecture that she may possibly have had a limited spell[vi] in the LTTE ranks and the wild thought that her parents may have purchased her demobilization from the LTTE ranks[vii] – speculative ideas that I did not present in public. In quick time, however, a friend brought my attention to a capsule version of the same tale under the same nom de plume in the Daily Telegraph on 3 May 2009, while one can find a highly abbreviated report in The Australian on 23 May 2009 under the revealing title “Cause remains for Tamil Tiger in Our Midst.”[viii]

It is this juxtaposition that I bring to the debate now. I ask readers to compare the short stories in different newspapers in mid-2009 with the longer book version of 2011. They will discover two Niromis, with both differences and overlaps.

In both the Daily Telegraph essay and book the tale is launched in melodramatic fashion by an account of de Soyza’s first alleged battlefield skirmish, one that is central to the unfolding composition in the autobiographical book because several of her bosom mates and one mentor died in that fiery encounter.[ix] [4] “At dawn that day, Indian soldiers had surrounded our hideout” she says in 2009. Later in this same account she notes that “fighting the Indian soldiers made no sense to me.” This realisation was one factor in her decision to extricate herself from the commitment to fight for Tamil independence under the LTTE.

In contrast, in the opening account in 2011, the enemy are just “soldiers;” while the back cover explicitly proclaims that “two days before Christmas 1987, at the age of 17, Niromi de Soyza found herself in an ambush as part of a small platoon of militant Tamil Tigers fighting the government forces in the bloody civil war that was to engulf Sri Lanka for decades (emphasis mine).”

In short, in 2011 the Indian presence has been obliterated at this critical juncture, though they figure occasionally at other points deeper in the book (pp. 162, 164, 168, 227, 264). The contrast with her initial foray in 2009 is an indication of deception catering to the Western world’s sustained criticism of the Sri Lankan state in 2011 within a backdrop created by the disclosures in Killing Fields and an UN panel report by so-called “experts.”

It is not difficult to conjecture why such a misrepresentation was injected into the new and expanded book-length version of her tale: foregrounding the Indians in the opening chapter would undermine the propaganda pitch as a Tamil patriot which is one dimension of Tamil Tigress. Readers in the West would assume that the soldiers were Sri Lankans because they were not versed in the complexities and temporal shifts attending Sri Lanka’s ethnic wars.

Our detective work is not that simple however. In both her public presentations, in 2009 and 2011, Niromi de Soyza tells the world that the Tigers were engaged in fighting the Indian troops of the IPKF as well as the troops of the Sri Lankan army during her alleged battlefield stint from October 1987 to June 1988. “The war resumed, just as Prabhakaran had predicted, though now we were fighting not only the government troops but the peacekeepers, too” she says in the Daily Telegraph account in 2009. She is consistent on this point. In 2011 she told Margaret Throsby in an ABC interview that “when I joined, the Indian forces had arrived and the Tigers had chosen to fight the Indian forces as well as the Sri Lankan forces.”[x] [5] During her leisurely chat with Nikki Barrowclough in Sydney in July 2011 she said that her unit spent “most of the time … running and hiding from government soldiers.”[xi] [6]

This aspect of her thinking has also been underlined recently by Darshanie Ratnawalli in Lankan newspaper accounts.[xii] Ratnawalli then asks a weighty question: how could any Tiger fighter not be aware of the identity of his/her adversary during the IPKF period of occupation?” This is precisely the issue that initially led me to suggest that Niromi was emulating Helen Demidenko and Norma Kouri.

Such sweeping suspicions are compounded when Niromi tells the world that (a) “during battles we had been trained to fire in the general direction of the enemy, not at individual targets, and I am not sure whether any of my bullets hit anyone;”[xiii] [8] and (b) that during her skirmishes as a guerrilla she may have shot at someone running, but “didn’t ever see a face… I would have frozen if I’d seen a face.”[xiv][9] In the result, Gerard Windsor concluded that “the Tigers were “amateurish” after his read of the book.[xv] As an admirer of the LTTE’s battlefield and organisational capacities over the years,[xvi] I find such a verdict quite mind-boggling. It is not Windsor’s error: it is induced by Niromi de Soyza.[10] Here, then, de Soyza does a disservice to the Tigers as a fighting force, while marking her profound ignorance about warfare.

These failures therefore lead me back towards the strong suspicion that she did not fight for the LTTE at all (though perhaps receiving some training before she extricated herself or was extricated). In these prevarications on my part I underline the several PUZZLES within Tamil Tigress that all readers should address. Together with several fallacious statements in the book which other commentators have noted, they cannot simply be dismissed as errors of memory or acceptable embellishments. In this respect it seems a far cry from the realties expressed by Shobashakti on the one hand and Umeswaran Arunagirinathan’s Allein auf der Flucht on the other – to judge from evaluations sent by Arun Ambalavanar and Maithri Samaradivakara respectively.

If Tamil Tigress had been cast as a novel or even a fact-based fiction its impact as a vehicle for reflection on the human condition and a softening of the perception of the Tigers as “terrorists” of a satanic kind would have remained forceful. When a whiff of deception intrudes, such reflective potential is diluted. Participants in the debate and future readers must ask themselves – in measured manner with analytical rigour of mind rather than emotional force of heart – whether they are being taken for a ride.

[i] Nikki Barrowclough, “Tigress, interrupted,” Good Weekend, 9 July 2011, p. 28.

[ii] A “memoir” and “autobiography” are synonyms at one level (English Thesaurus, 2006, Geddes & Grosset, p.156); but a memoir has a wider range and encompasses “biography.” Both forms are regarded as historical accounts grounded in truth so that a ‘memoir’ is even defined as “an essay on a learned subject specially studied by the writer” (Oxford English Dictionary, p. 905).

[iii] Roberts, “Niromi de Soysa’s Path of Redemption with Deception? or Both?” 27 October 2011, http://thuppahi.wordpress.com/2011/10/27/niromi-de-soysa%E2%80%99s-path-of-redemption-with-deception-or-both/

[iv] Cf. Stephen King, “Deceiving Consumers: impressions count when it comes to misleading consumers,” http://thuppahi.wordpress.com/2011/12/19/deceiving-consumers-impressions-count-when-it-comes-to-misleading-consumers/

[v] Note John Taylor, “India’s Vietnam,” in http://in.rediff.com/news/2000/mar/23lanka.htm.

[vi] One “ex-Tigress” blogger indicates that a lass named Nirmala died in December 1987 at the same time as “Murali anna and Kanthi anna” (Blog No 58 10 Dec. 2011); while someone writing as “BenJ” (12 Dec. 2012) says both Nirmala and Niromi joined Pirapāharan’s batch of recruits – comments in Jeyaraj “From Shenuka to Niromi: “True Tale of a ‘Tamil Tigress,” 9 December 2011, in http://dbsjeyaraj. com/dbsj/archives/3160.

[vii] Note that this idea is also raised independently by one blogger with the nom de plume, “Puma,” in his/her comment within the article by DBS Jeyaraj: “Many middle class parents ‘bought’ their children back from LTTE in late 80s and early 90s …” (Jeyaraj, “From Shenuka to Niromi: “True Tale of a ‘Tamil Tigress,” 9 December 2011, in http:// dbsjeyaraj.com/dbsj/archives/3160).

[viii] This title was probably created by reporter Drew Warne-Smith, — see http://www.theaustralian.com.au/ news/nation/cause-remains-for-tamil-tiger-in-our-midst/story-e6frg6nf-1225715005848.

[ix] As recounted in “The Last Few Moments of Life,” Chapter 14.

[xi] Good Weekend, 9 July 2011, p. 28.

[xii] Ratnawalli, “And Quietly Ignores Them Hoping They Will Just Go Away,” http://www. thesundayleader.lk/2011/12/18/and-quietly-ignores-them-hoping-they-will-just-go-away/. Also see http://ratnawalli.blogspot.com/.

[xiii] “Life as a female Tamil Tiger guerilla relived by one of first female soldiers,” http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/srilanka/5283438/Life-as-a-female-Tamil-Tiger -guerilla-relived-by-one-of-first-female-soldiers.html

[xiv] In Nikki Barrowclough, “Tigress, interrupted,” Good Weekend, 9 July 2011, p. 28.

[xv] Windsor, “Tamil Tigress,” http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/tamil-tigress-20110901-1jmmv.html.

[xvi] Roberts, “Pragmatic Action and Enchanted Worlds: A Black Tiger Rite of Commemoration,” in Social Analysis, vol. 50/1: Spring 2006, pp. 73-102. See http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ berghahn/socan/2006/00000050/00000001/art00005.