Book review of:

Palitha Perera Samaga Sajeeva Lesin

(Live with Palitha Perera)

Surasa Books, Colombo; 2008

‘What does Palitha Perera know about culture? He’s just a cricket commentator!’

That’s how a senior banker reacted when veteran broadcaster and journalist Palitha Perera’s name was proposed as script writer and narrator for a TV documentary series on Buddhist temple murals in Sri Lanka. When Palitha heard this, he realised how, in the minds of many Sri Lankans, he was pigeon-holed into a single niche. This prompted him to write his first book, capturing highlights of a long and illustrious career of over 45 years during which he has straddled multiple spheres of radio and TV broadcasting, cricket commentating, sports journalism, arts and culture. And blazed new trails and left his mark in several of them.

However, Palitha Perera Samaga Sajeeva Lesin (Live with Palitha Perera; Surasa Books, Colombo; 2008) isn’t another ego trip of a book, the kind that senior journalists have been churning out in recent years. It’s not written in the ‘been-there, done-that’ style of self importance. True, it has a rich sprinkling of autobiographical details expressed in Palitha’s lucid, entertaining writing style. But in recalling men and matters, and his own multiple roles in shaping events, he is both modest and moderate — hallmarks of his professional career.

His reminiscences provide some unique insights into our broadcasting history for nearly half a century. He chronicles little known facts and praises unsung heroes. In doing so, he offers a ringside account of the progress — and decline — of state broadcasting in Sri Lanka from the early 1960s to the present.

Having commenced its regular transmissions in December 1925, just three years after the BBC, Radio Ceylon was the first broadcasting service in Asia. By the 1950s, it had built up a reputation for being one of the finest in the region — this was still the case when young Palitha Perera joined in 1963. Only a decade earlier, it was an overseas broadcast of Radio Ceylon that Edmund Hillary and Tensing Norgay heard when they turned on their transistor radio soon after conquering Mount Everest. They joined millions of others from across the Indian subcontinent who regularly tuned in to these broadcasts, which at its peak had an audience many times the population of Ceylon.

How times have changed! The once popular, trusted and influential state-owned radio in Sri Lanka has been completely sidelined in the past 15 years. A cacophony of privately owned channels now crowd the airwaves — almost all on the FM band — and compete with each other to inform, entertain and sometimes titillate 20 million Sri Lankans. The product of media liberalisation undertaken from the early 1990s, these channels have taken the radio medium closer to their listeners by talking in a more colloquial language, putting ordinary people on the air and adopting other populist methods.

Innovation stifled

Yet, as Palitha diligently documents in his book, many innovations can be traced back to the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC), successor to Radio Ceylon. For example, the country’s first FM service, called City FM, was introduced by SLBC in November 1989 with Palitha as its pioneering director. The now common practice of allowing listeners to phone in to live radio shows was started by SLBC Educational Service in 1995, initially as a tentative experiment.

Rather unfortunately, the grand old dame of Torrington Square never had a chance to aspire to her true potential. Early on, our political parties realised the power of the airwaves and never allowed SLBC to evolve into a public service broadcaster that it was meant to be. Over the years, governments of different political colour and hue persistently misused the station for their narrow, partisan needs. State broadcasting in Sri Lanka is misinterpreted as government broadcasting which in turn is reduced to shameless propaganda.

This perversion is at its worst in the news bulletins, which over the years have become daily chronicles of the head of state and powerful ministers, never mind the real news. To find out what was really happening in their own country, discerning listeners used to turn to foreign radio stations on shortwave, especially the BBC. As soon as SLBC’s decades-long monopoly ended, audiences migrated — and advertisers quickly followed. SLBC stays on the air today largely thanks to Treasury (i.e. public) funding.

It is one of history’s little ironies that the country’s leading mental hospital was once located at Torrington square in the buildings that were later assigned to SLBC. Having cut my own teeth in broadcasting at SLBC, yet never a great fan of that institution, I have often wondered what dogged curse made that location progress from mad house to whore house. For prostituting the airwaves is what state broadcasting in Sri Lanka is best known for, then as now.

The institution’s saving grace has been a handful of dedicated and versatile broadcasters who fought excessive bureaucracy and political interference to serve their true masters: the listener. Palitha Perera is a fine example of this now rare and endangered species. Trained in the finest traditions of public service broadcasting in Germany, UK and United States, he stood up for his journalistic integrity and professionalism at SLBC when these values were decaying all around him. When he couldn’t stand it, he resigned in October 1997 with his dignity and reputation intact.

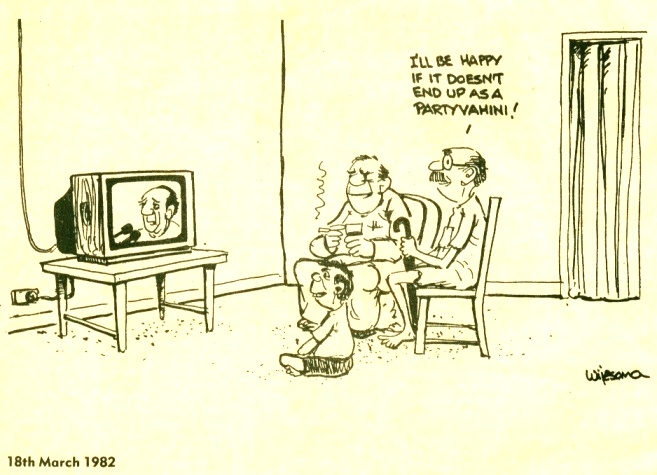

Cartoonist Wijesoma saw it coming: this first appeared within a month of Rupavahini’s inauguration (courtesy: The Island)

Palitha’s book is a reminder of many opportunities we collectively missed in post-independent Lanka to harness the airwaves for building and uniting the nation. Perhaps he had no such grandiose intentions when he finally put pen to paper. He just tells fine, authentic and moving stories as he has always done, first on radio and later on television. These are drawn from his many and varied experiences with personalities as diverse as Martin Wickramasinghe, Gamini Fonseka, Rukmani Devi, H M Gunasekera (all of them no more) as well as living national treasures like Amaradeva and Nanda Malini.

First draft of history

Journalists write the first draft of history. Their hurried, often transient reports are invaluable eye witness accounts for historians. Palitha’s book revisits some key moments in our island’s recent history and records for posterity aspects that might elude traditional historians. And he gently chronicles a few occasions when he made history himself.

Among other feats, Palitha holds the distinction of having been the inaugural announcer on two Sri Lankan TV channels – Rupavahini (15 February 1982) and TNL TV (21 July 1993). For several months in 1994, he hosted the country’s first political interview series (Pilisandara) on TNL TV where he adopted (British broadcaster) David Frost’s style of penetrative questioning.

In his time, Palitha has interviewed dozens of public figures from Presidents and prime ministers to social activists and trade unionists. He is always prepared and well informed. He remains calm and friendly at all times, yet is dogged in his questioning. This style has exposed many a hypocrite and charlatan — one academic turned politician even complained to the head of state about the ‘audacity’ of this man who cannot be manipulated!

But it was as Sri Lanka’s pioneering cricket commentator in Sinhala that Palitha has had the greatest impact on our culture and society. In his youth, he played inter-school cricket and was also an avid listener of test cricket commentaries on BBC World Service radio. This background no doubt helped him when he was tasked to do the first ever ball-by-ball live radio commentary in Sinhala in March 1963, just three months after he joined Radio Ceylon. That historic broadcast covered the Ananda-Nalanda annual cricket encounter, which was played at the Colombo Oval (later P Saravanamuttu Stadium).

It took several years of hard work and persistence for Sinhala commentaries to become popular. In 1972, Palitha invited and involved a witty school master named Premasara Epasinghe, thus sparking off one of the most enduring partnerships in Sri Lankan broadcast history.

The book offers an authentic account of how Sinhala cricket commentaries found its own place in the sun. Early challenges included coming up with the right Sinhala terms for the very English game. Having found scholar-proposed technical terms completely unsuitable, he developed his own vocabulary which he delivered in his uniquely passionate style influenced by the BBC’s legendary commentator John Arlott (1914-1991).

Here we have, straight from the original source, the story of how cricket became the de facto national past-time, if not our national addiction or religion! Like it or hate it, cricket is an integral part of our popular culture. Radio (and later TV) cricket commentaries take much of the credit (or blame, in some people’s view) for building up this uncommon fervour that occasionally unites our otherwise utterly and bitterly divided nation. Many of our national players acknowledge being inspired by cricket commentaries of Palitha and Epa.

With his deep, clear and friendly voice, Palitha has enthralled millions of cricket fans with commentaries on matches at every level. What’s remarkable is that he has done this for two generations and still keeps batting, slowly moving towards his own half century. This book offers only a few glimpses of what must surely be a treasure trove of memories. It’s with nostalgia that Palitha recalls the less frenzied times in the 1960s and 1970s when big money had not yet arrived and cricket was played for fun and passion. Achieving Test status in 1981 changed all that forever.

Rebel tour

Shortly afterwards, Palitha became the first journalist in Sri Lanka to be questioned by the Police Criminal Investigation Department (CID) over a media report relating to sports. It was his probing of cricket and politics that earned him this dubious distinction.

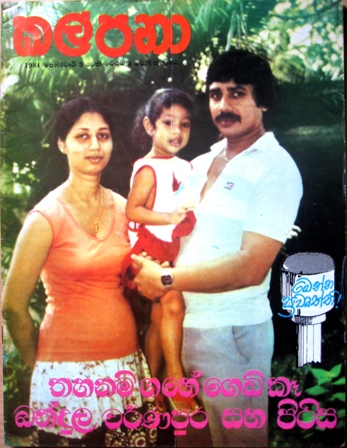

For over two hours on 19 April 1984, he was grilled about a controversial story he wrote for the leading current affairs magazine Kalpana about the Sri Lankan rebel cricket tour to South Africa. The tour, which took place in October – November 1982, rocked the cricket world and scandalised the country’s Cricket Board. The rebel players, headed by first Test captain Bandula Warnapura, were promptly given a life ban (revoked years later).

Although the tour and its political fallout had been covered extensively in the local and international media, Kalpana editor Gunadasa Liyanage, a fearless investigative journalist, felt the rebels’ side was still under-reported. He commissioned Palitha to uncover the ‘story behind the story’. Kalpana’s February 1984 issue featured indepth interviews with Warnapura and tour organiser Tony Opatha, as well as profiles of all participating cricketers.

The explosive story sold out quickly, and brought up some unpleasant truths about the state of Sri Lankan cricket. This prompted the Board’s then Chairman (and powerful Mahaweli minister) Gamini Dissanayake to complain to the CID, triggering the criminal investigation. It was suggested that Palitha might have been bribed by the rebel cricketers (who were paid handsomely by South Africa). Then, as now, the knee-jerk reaction to media exposures is to harass (or shoot) the messenger.

It’s only now, more than two decades later, that Palitha reveals details of his close encounter at the notorious ‘fourth floor’ of the CID. The interrogator turned out to be a fan, which diffused tension. Palitha answered all his questions, reacting sharply to the recurring query on who paid him to write the story. Yes, he was paid for the articles, Palitha said — it came from the account of Kalpana magazine, which was sponsored by the state banks. But no, he would never solicit or accept any other money for media coverage ‘even if I had to beg on the streets’. For good measure he added: ‘I consider it the most degrading question ever asked of me’.

The investigation ended there, and no charges were pressed. Palitha continued in his job at SLBC with no harassment. In fact, he writes affectionately about Gamini Dissanayake and then SLBC chairman Livy Wijemanne. They were true gentlemen who bore no grudges, he says.

I find Palitha to be the same. In more than 400 pages, I couldn’t find a single grudging remark. He is a sensitive, dignified man who was unfairly treated, or simply sidelined, on many occasions during his 35 years of loyal service to state broadcasting. He looks back with amazing equanimity at how men with less talent and fewer principles rose to high echelons at the houses of ill fame that are SLBC and SLRC. Reading his book reminded me of Lincoln’s famous words: “With malice toward none, with charity for all…let us strive on to finish the work we are in.”

A freelance broadcaster for the past decade, Palitha carries on his life’s mission of enriching our airwaves. He sure knows there’s much unfinished business, and miles to go before he can sleep.

Nalaka Gunawardene blogs on media, society and culture at http://movingimages.wordpress.com. Having been a regular presenter and guest at SLBC for years, he resolved in 1996 never to set foot there again.