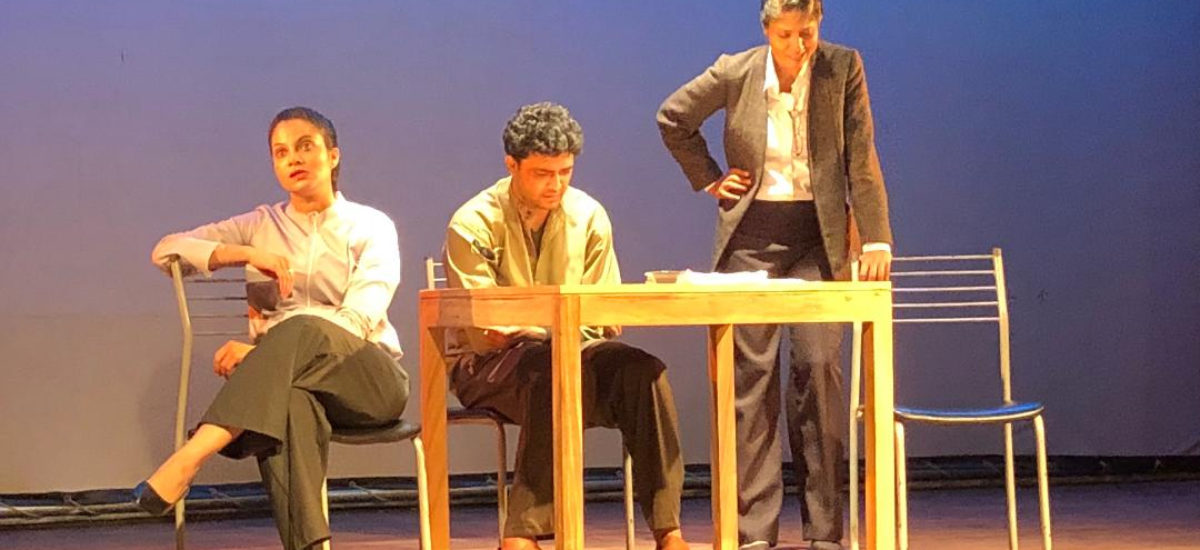

Featured image by Joys Chokatte

Editor’s Note: An abbreviated version of this review first appeared in this week’s edition of the Sunday Observer

On July 7 and 8, Irish playwright Martin McDonagh’s award winning play ‘The Pillowman’ was presented at the Punchi Theatre in Borella by Stage Light & Magic Inc. Yours truly was at the Punchi Theatre on closing night. This production marked the directorial debut of Shannon Misso and featured the acting talents of Yasas Ratnayake, Biman Wimalaratne, Bimsara Premaratne, Ashini Fernando, Swasha Perera and Tracy Jayasinghe, and was produced by Dininda Paranahewa.

The premise of the play builds on how two police investigators named Ariel and Tupolski (played by Ashini Fernando and Bimsara Premaratne respectively) interrogate a fiction writer named Katurian, played by Yasas Ratnayake, over a spate of gruesome child murders which appear to have been ‘executed’ similar to descriptions found in his fiction. The action takes place in an interrogation room and detention cell in an unnamed totalitarian state where there is clearly no criminal justice system with court hearings. The police authorities are shown to be judge, jury and executioner. The task at hand for the police is to determine if the crimes were committed by Katurian or his mentally handicapped elder brother Michal played by Biman Wimalaratne.

Joys Chokatte

The stagecraft was somewhat a minimalist setup and not of Chekhovian realist design. There was use of multimedia projections on the background at several points in the narrative that clearly made Misso’s directorial craft a somewhat mixed-media method. How much stage acting is impacted when video material is screened on stage to add to the overall narrative in a stage play is a matter I have commented on in my reviews of Jehan Aloysius’s ‘Stormy Weather’ (reviewed in the 9/4/2017 issue of the Sunday Observer) and ‘Twelve Angry Women’ directed by Kevin Cruze (reviewed in the 3/12/2017 of the Sunday Observer). Misso’s direction didn’t present live action video footage unlike in the aforementioned plays, but 2D graphic animations of a cartoonish form which adduced a children’s story effect to the scenes where they were featured as part of the narrative’s nonverbal aspects. This element contributed to inject different effects to the mood pervading from the stage, and was an accompaniment to the parts played by Swasha Perera and Tracy Jayasinghe who (re)presented a space that seemed of imagination and reminiscence bound to the collective mindscape of the brothers Katurian and Michal.

I honestly thought the first of these animations projected on the background was superfluous, distracting and didn’t perform a function complementing Perera’s and Jayasinghe’s creditable acting. However some subsequent animations as visual components to the narratives by Perera and Jayasinghe, contributed more productively. In this regard the animation of the dark hooded rider was significant. An added eeriness was certainly infused by the animated graphics element at that juncture of the performance.

‘The Pillowman’ is clearly for mature audiences and not a show that offers light hearted entertainment and doses of comedy. If one is to label the subject matter in terms of the mood and feeling it pervades, it can surely be called ‘morbid’. Although pre-show press publicity called this play a ‘dark comedy’ I did not find anything comedic about this story in any shade. Yet we Sri Lankans seem to possess a vein of being addicted to ‘the need to laugh’. Sri Lankan theatregoers are ones who can keenly find an opportunity to laugh when at the theatre despite how incongruous laughter is in relation to the action on stage and its context.

I have commented on this aspect of audience reactions in several reviews, examples being my review of ‘Dasa Mallige Bangalawa’ Directed by Ruwan Malith Peiris and Kalana Gunasekera (published in the Sunday Observer in two parts on 9/11/2014 and 16/11/2014) and my review of ‘The Irish Curse’ directed by Gehan Blok (published in the Sunday Observer on 16/08/2015). And so, commenting on ‘the realities of laughter when at the theatre’ I found it rather perturbing how some audience members found Michal’s character affording opportunities of laughter. The most notable of those instances being when he calmly repudiates Katurian ascribing him the quality of ‘Jack the Ripper’ and proceeds in a childlike way to differentiate his method of butchery from Jack the Ripper’s. I believe instances like that reveal how audience members may read the performance and scene outside the character and context. A mentally handicapped adult was speaking in the manner of a child about how he butchered children. And his way of acting it out was for some, good enough for a laugh. Perhaps that was the calculated moment for a comedic darkness to spring up in the audience? I can only add conjecture. I will not presume to declare what the director’s intention could have been.

In creating personae onstage who ‘are not quite normal’ from their aspect of ‘mental functions’ Misso’s approach with Michal and his mindscape ‘self’ was quite interesting. Opting to give a gender switch to Katurian and Michal in their ‘mindscape’ portrayal as not so much brothers but a mother and daughter scenario, it was perhaps a means to explore a rendition of Katurian’s character as having almost maternal affection for his older yet disempowered brother, and Michal’s own reflective image being that of a female child who seeks the warmth and protection of a nurturing mature figure.

In giving life to the complexities of Michal, Biman Wimalaratne and Tracy Jayasinghe were compelling, absorbing and delivered praiseworthy performances. At a certain point in the play Jayasinghe, when delivering her part of dialogue (or perhaps more practically a monologue) seated in a chair in the foreground of the stage, had an expression drained of emotion, deadened within, which compounded with the white light cast on her, made her countenance strikingly sepulchral. It was subtly haunting, silently commanding and had me transfixed on the character on stage. This was an instance evincing a skilled blending of Misso’s directorial craft with Jayasingh’e innate thespian talent.

Wimalaratne delivered his character with a rhythm and pace that behaviourally externalised the emotional interiority of Michal as an amoral child trapped in a man’s physical frame, yet unconquered in mind and soul by the chronology of the human body. The character came out in my opinion as mentally challenged by autism, rather than in the case of a person who is clearly developmentally disabled. I do not purport to be an expert on the subject but Michal was no ‘Down syndrome case’ by any means. The fluxes of the interiority of Michal, which exists beyond the logic of the moral binary of right versus wrong, were displayed outwardly with tone and pace of dialogue with complementing physical actions and facial expressions that were persuasive. The placidity within Michal and its shattering, when made to grapple with the matter of his childhood torment at the hands of his abusive parents, were projected as impressions with impact.

Misso’s casting of two seasoned actresses of the stage to play Ariel and Tupolksi casts an interesting thesis on ‘gender roles’ in society. The general expectation would be to see two burly men playing ‘good cop, bad cop’ or in this case bad cop, worse cop! Clearly the directorial conceptualisation of McDonagh’s The Pillowman had a facet of gender politics involved in it. A thought provoking creativity that was convincing when looking at the persuasive demeanour projected by Fernando and Premaratne were juxtaposed to a robustly build male whose demeanour was subdued and not possessed of redoubtable resistance. Yasas Ratnayake in his portrayal as Katurian was good but could have been better by exploiting opportunities for inner deadened silence. Ratnayake’s performance rested mainly on bringing out anxiety, terror and revulsion through noticeably theatrical expressions. Swasha Perera played a commendable role as the mindscape image of Katurian the storyteller who seemed larger than life in the eyes of her primary listener.

The Pillowman is a story that unfolds between two captives and two captors. The captors themselves are captive(s) in the system they serve. In that kind of ‘state of affairs’ ‘citizens’ will at times have to chose one of two ends of a spectrum – be a victim or a victimiser. The latter too is often psychologically another manifestation of being the former. This seems especially the case with Ariel who is troubled by a childhood of molestation. Do enforcers in a police state really have the luxury of choice? Do they wholeheartedly agree with what they do and enjoy it? The answer is not apparent by any means in The Pillowman. Though Ariel is shown in the light of a sadistic interrogator this character too is an instrument of the system directed to achieve an end with no questions asked about the means adopted to achieve the end. This is one of the consequences of a police state that is so regimentally driven that its operators are almost mindless and mechanical. Their own conscience has been stifled for the simple need to survive in a binary system of victim or victimiser.

It is also worth noting that despite being inhuman torturers both Ariel and Tupolski are conscientious about achieving their goal. They are determined to find the killer and end the crimes and not merely hang someone and declare the killer punished. Here is an interesting point to ponder on how the interests of a totalitarian state may differ from a democracy that needs to appease the public’s demand. The police state doesn’t consider itself answerable to its people with a need to expeditiously provide the perpetrator(s) of a crime that has evoked public outrage, as a convenience to ensure public confidence in the criminal justice system. The police state wants to root out the problem without regard for the means. All that matters is the end(s). This critical discourse that can be seen from the story of The Pillowman provides an interesting viewpoint in light of how recent political events in Sri Lanka have sparked public debate over what ‘measures’ are needed for expeditious crime curtailment. The debate perhaps even asks does democracy really matter if all the people want are simply ‘results’ at any cost, not realising that ‘results’ are not necessarily ‘solutions’.

If looking at how society functions as the nexus of persons and functions regulated by laws, bound by duties and responsibilities and consequences, in whom is the blame rooted for the child killings? Was it the abusive parents who couldn’t face the fact their first born was mentally handicapped? Was it the writer for having written what he did, not realising his works could affect his ‘readership’ into living out the stories? Or was it simply Michal, the one of unsound mind?

What does the Pillowman stand for as a symbol? In a way I saw this dark fictional character as somewhat a facilitator of ‘self administered euthanasia’. Perhaps that’s a dramatic description to describe his function of visiting people’s childhoods and convincing the child to commit suicide and be spared of the future misery of an unhappy life. But what is suicide but a desperate bid to seek exit from a state of suffering that cannot be borne any longer. On another level I feel the Pillowman’s idea of preventing suffering by impelling the death of the child can be abstractly looked as erasing the child within adults, who despair when they look back to happier days of childhood. Maybe the Pillowman as a symbol is the concept of smothering the voice and memories of the child within.

When Katurian tries to cut a deal with the police to admit guilt to the crimes his one hope is to save his unpublished writings from being destroyed. Every writer and artist believes that he will be survived by his works. And here comes the conflict between the State that sees Katurian’s works as destructive and harmful to society and the writer who seeks the chance to preserve his work and not be completely erased from human memory. Here comes the debate of censorship and what justification it may have in the interest of public good.

In his preface to ‘A Picture of Dorian Grey’ Oscar Wilde has written ‘All art is quite useless.’ In his book ‘Sculpting in Time’ the master Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky says “It is obvious that art cannot teach anyone anything, since in four thousand years humanity has learnt nothing at all.” Both Wilde and Tarkovsky make their remarks in the light of seeing art as being incapable as a force for salutary change in humanity. It is a commentary on the didactical inability of art to be a force for good.

When considering creative writing as part of art(s), although the aforementioned statements of figures of world reknown may not see the arts and letters as a force with power, The Pillowman shows how Katurian’s writings found a reader dedicated to realise what he found to be imagined directives to give the fiction that captivated him credibility beyond the pages. It was Michal’s way to legitimise his brother’s fiction as potential reality. Does art really remain an impotent entity, when it finds an audience that bonds with it to the degree of willing to existence a truth that erases boundaries between art and reality? Among the many ways in which ‘The Pillowman’ can be viewed is as a work that explores nexuses between art and behavioural psychology.

Stage Light & Magic Inc must be congratulated for presenting an appreciable production of The Pillowman to theatregoers in Colombo. This noir stage play was certainly a successful directorial debut for Shannon Misso who will hopefully contribute further to enrich Sri Lanka’s growing theatre scene.