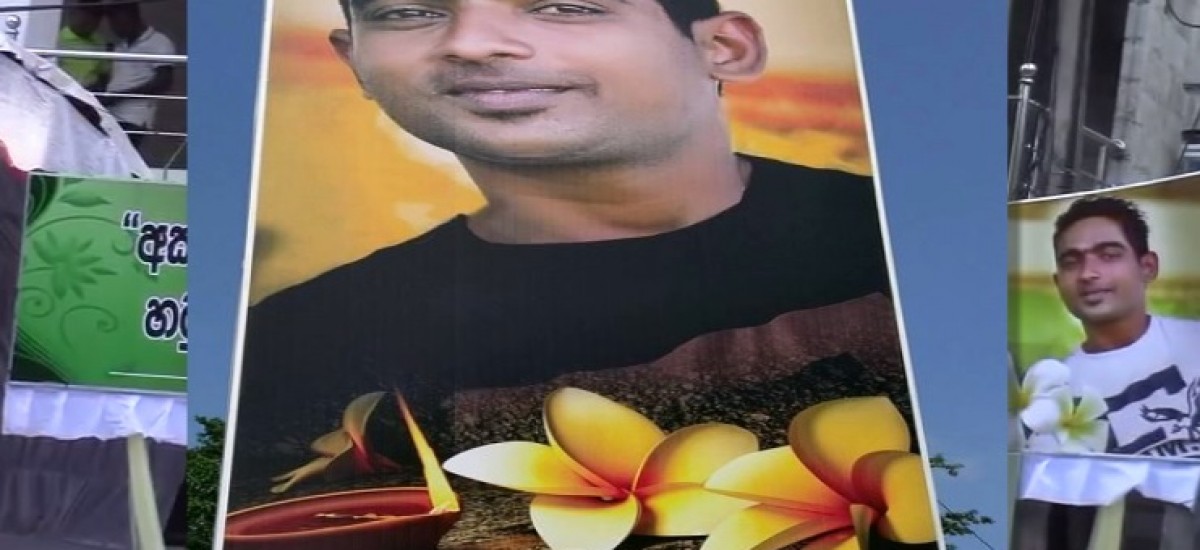

Photo courtesy News1st

Sumith Prassana Jayawardena would not normally be a household name. But his sudden and violent death in Embilipitiya following an altercation and clash between guests and the Police at a social function, has become an issue of national interest and indicates the challenges of implementing Yahapalanaya. The story line in Embilipitiya is not unfamiliar in Sri Lanka. There is a clash between citizens and agents of the state, a citizen (or citizens) dies and life goes on. Occasionally as in Embilipitiya, as with Weliveriya and the Free Trade Zone, before this, there is a social outcry for justice, multiple investigations are launched until public attentions drifts and nothing comes out of it. The “Trinco Five” and the Prageeth Eknaligoda case are different because they seem prima facie to be abduction and murder and both are now before the Magistrates Courts, the former proceeding much slower, than the later.

However these issues come at a time, domestically and internationally when the status quo of a culture of impunity, is being challenged and is due for a change. Domestically the election of President Maithripala Sirisena in January last year and the subsequent election of Ranil Wickramasinghe as Prime Minister on a platform of good governance and state sector (as well as economic) reform means, that there is a serious reconsideration of the nature of governance of the country. Basically post the war, the Mahinda Rajapakse Administration continued to govern Sri Lanka, as if a war was still on, with the same mindset, the same restriction on civil liberties, the same ethnic polarization and the same primacy or mantra of national security above all else. It was a formulae that wore thin among a majority of Sri Lankans, despite heated nationalist rhetoric as the election results of January and August, last year bear out.

Another fundamental difference since August last year, has been the establishment of the Independent Commissions, including the Independent Human Rights and Police Commissions. These two institutions have already started to act genuinely independent of the Executive and the difference from the Rajapakse years, is that there is no overt or covert pressure on them to white wash wrongs and sweep things under the carpet. Accordingly Independent Institutions, often now headed and staffed by civil society actors and those who genuinely believe and are committed to the principles of good governance and institutional reform are holding the executive branch including law enforcement and the security establishment to account. What state agents are finding is that the usual political pressure brought upon independent institutions to back off, beyond the farcical charade required to demonstrate some actions for international and domestic consumption, is missing this time.

Internationally Sri Lanka is making a comeback as a proud and equal member of the community of nations, distancing ourselves from the near pariah status to which the Mahinda Rajapakse foreign policy, managed by Professor GL Peiris and Sajin Vass Gunawardena had led us to. From seeking to regain the GSP Plus status for our exports to the European Union, which is largely dependent on our human rights situation, to the UNHRC process on accountability, Sri Lanka’s foreign policy has a new focus on human rights that would serve our economy and our people well. The world is watching closely to see if the Maithripala / Wickramasinghe Administration is genuinely committed to and implementing the program and policies of reform which it promised the electorate at two elections and which were mandated by the sovereign people of Sri Lanka.

During Sri Lanka’s near three decades of war, there was a near national consensus and a clear governing elite’s consensus that as Cicero argued in the Roman Senate and as quoted by then President JR Jayawardena “in the fight of good against evil, the laws must be silent”. Initially there was the attempt to contain this maxim to the theatre of conflict, but over time it spilled over to the South and was finally used throughout the country. The final targets of the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), were Azath Sally and Tissanayagem, one a politician and the other a journalist, both opponents of the then Rajapakse Administration, but never terrorists by any definition, except in the PTA and a pliant Attorney General’s Department.

The Rajapakse’s and their ideologues would argue that human rights is a western concept and that any argument in favor of a citizen or an individual’s right, is not in the national interest. That the primacy of the interest of the state and her agents must be paramount. However as history, including our own has shown us, it is power as much as the individual, who requires laws to contain and to be managed. Unchecked power is always dangerous. As Lord Acton was to famously state, “Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely”. Absolute and unchecked power to the state only weakens and disempowers the citizen. At a time when we are taking about constitution making and the sovereignty of the people in our Sri Lankan republic, such sovereignty is not only exercised through our collective identity in the State, but also in our fundamental individual rights, including that most basic right to life, a right which was denied to Sumith Prassana Jayawardena, Prageeth Eknaligoda and the Trinco Five among many others. To the extent we hold those responsible accountable and eliminate the culture of impunity or state agents operating above the law, we have come a long way as a nation.

(The writer is the Chairman of the Resettlement Authority of Sri Lanka. The views expressed are personal).