Just over ten years ago, a powerful undersea earthquake caused a devastating tsunami that wrapped around two-thirds of Sri Lanka’s coastline on Boxing Day, at around 8:30am. Being a holiday, locals were fishing, bathing and playing on the beaches. Within a matter of minutes some 35,000 people were dead, thousands were missing and over half a million survivors would soon be displaced.

Having lived in Sri Lanka a few years before the tsunami struck, I became concerned about the situation and contacted various aid agencies in Australia to see if they were putting together any teams of volunteers. I found out about an organization called Volunteers Sri Lanka, which was working in the recovery effort on the ground. I joined their outfit and over the course of three months I mainly helped build relocation homes for families in the South and East of the country.

I arrived a few months into the relief effort, and decided to first visit the village and house where I had stayed in 2001, situated on the beautiful Southern coastal stretch of Sri Lanka. The son of a Sinhalese family I had lived with greeted me with a certain sense of both relief and grief. He explained that his father had been killed in the house on that fateful morning. Taking a look at the construction, with only part of the wall left standing and all the neighbouring buildings flattened, the seriousness of the disaster began to sink in. I picked up a stone from the residence, which had brought me so much joy back in 2001 and put it in my pocket with the permission of the son, who was visibly distraught.

A kilometre back from the sea, international aid agencies had already been through, setting up portable wells and some temporary shelters for the affected. A Sinhalese man I met in the South told me he had lost his wife, two daughters and his home, and philosophically added: “This is Sri Lanka, what to do?”

If the Buddha was right in saying, “All life is suffering”, then this island has had more than its fair share over the years.

In June 2005, I spoke to a fragile Tamil woman in the East, who said she had nightmares of gunfire, grenades exploding and of another tsunami happening, but was grateful that foreign aid workers were bringing some assistance to her village.

Much of the tsunami-affected families were still living in temporary shelters, tents or refugee camps in the Northeast for the months that followed.

Surveys at the time suggested that congestion and a multitude of other hardships had made daily life inside the dwellings nearly impossible. Many social problems were on the rise from this kind of transitional living.

With livelihoods taking a hit, drug and alcohol dependency were at an all time high and many survivors were suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Women inside the shelters said they felt unsafe at night. As volunteers, we faced some safety issues building the shelters, particularly during the monsoon months because of loose electrical wires that could cause electrocution during the rain.

Long-standing conflicts over land, exacerbated by the mass displacement of people, complicated matters further and the government was struggling to deliver any lasting solutions. There was a mood within some of the affected families that it would have been better to die in the tsunami than to have had to live through that kind of suffering.

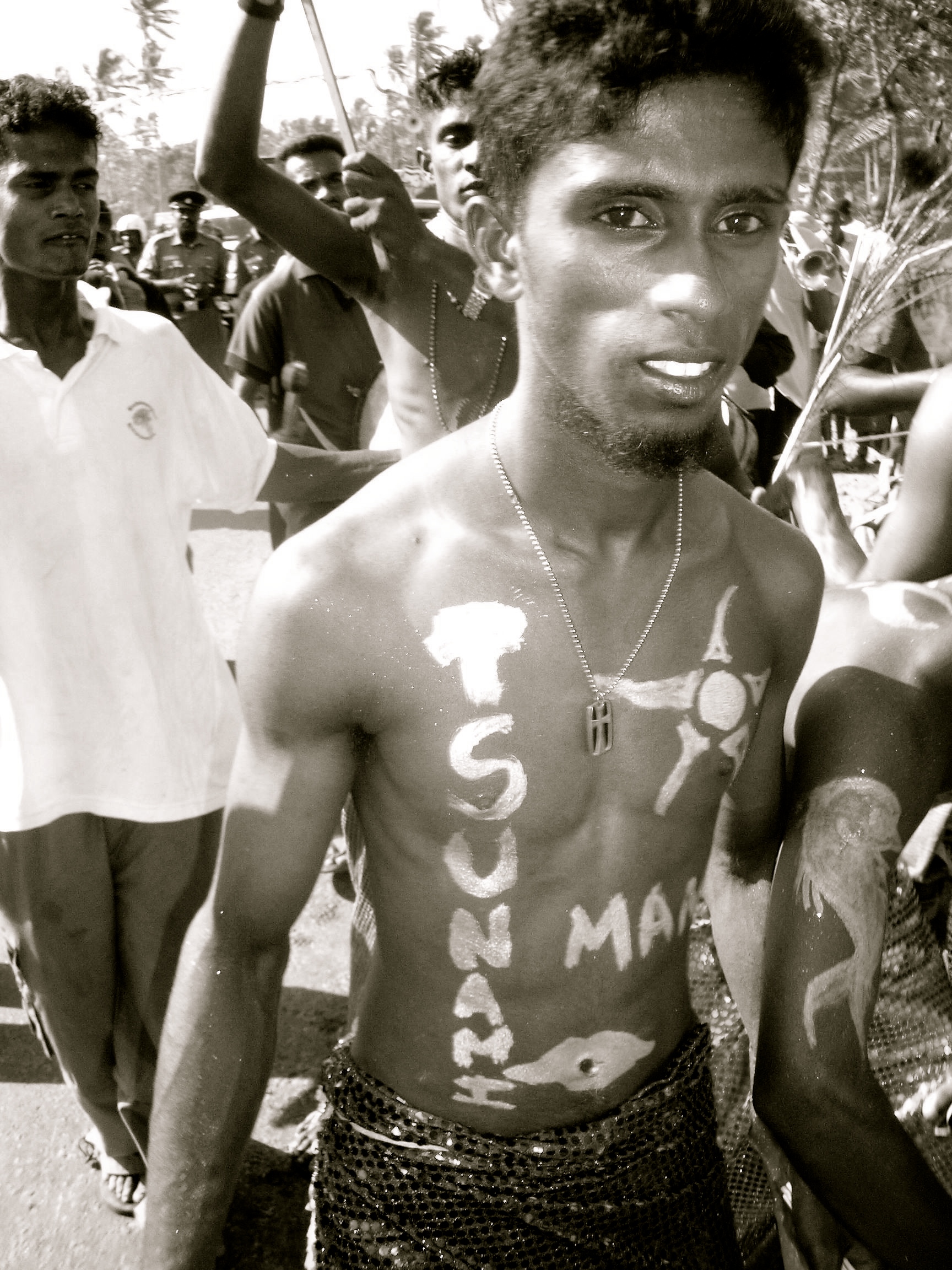

The 2005 Vesak Festival in the South was larger, brighter and more colourful than other years before, locals told me. It appeared that the event was a stage for exercising some of the ghosts of the tsunami.

Galle Road in Ambalangoda became a moving carnival of theatre and spirituality for the young and old. Locals were decorated in body paint, traditional masks and other costumes, carrying conches, trumpets and drums. The parade proceeded along the coast winding up at the local Buddhist temple late in the afternoon. By nightfall a crowd had gathered inside the place of worship to watch an array of performers wooing the congregation with firewalking and devil dancing. For the first time, I had a sense that some of the Sri Lankan people were again smiling.

18 months on and the country was still in deep crisis, millions of dollars in donated aid had allegedly been misappropriated. Again there was a sense that there might be a return to full blown war.

The Tamil population in the North were becoming more desperate and a September 2005 report in the Tamil Guardian, suggested that the state, fuelling the rising tensions, were obstructing international aid destined for the Northeast.

Velupillai Prabhakaran, the former leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) gave the Sri Lankan government until 2006 to reinstate a Tsunami Joint Mechanism for the sharing of international donor money and also to reach a deal of autonomy in the North, threatening that if not, the LTTE would ‘intensify’ their struggle.

Mahinda Rajapaska, the then newly elected president, refused to acknowledge any such demands. In the meantime, there had been increased fighting in the Northeast between government troops and the LTTE ranging from aerial strikes to landmine attacks.

This was not where Sri Lanka wanted to be after a devastating tsunami and over twenty years of civil war. Many people felt the 2005 national election was a disappointing outcome for any hopes of a peaceful Sri Lanka.

In the lead up to the election, the European Union (EU) observation team offered me a job as an election monitor in the North. However, due to security reasons and large insurance costs the assignment was cancelled. Those who monitored the ballot spoke of intimidation, reprisals and blatant vote rigging. The political wing of the LTTE put out black flags on Election Day warning Tamils not to vote.

From the LTTE’s point of view, they seemed to have no faith in either candidate. Talking to many Sinhalese in the South it appeared that a number of Tamils and Sinhalese could agree on something. What was then needed was good diplomacy from all sides for the peace talks to flourish and to keep Sri Lanka from sliding back to civil war again.

All prior peace envoys failed and after a 26-year military campaign, which killed over 70,000 people, the Sri Lankan military eventually defeated the LTTE and shot dead their leader in May 2009.

Ten years on, the tsunami recovery is largely finished and the war is over, but the country still needs international support. Sri Lanka relies heavily on tourism to keep its economy moving. One way for the foreign community to mark this recent anniversary is to visit the island and enjoy spending their tourist dollars in a fragile paradise.

###

All photos by the author.