Introduction

Since the end of the war in 2009, reconstruction and development in Sri Lanka has centred primarily on rapid economic development (Bopage, 2010; Goodhand, 2011). This can be seen in the current drive to transform Colombo into a “world-class city”, as a “preferred destination for international business and tourism” (Secretary of Defence and Urban Development). The improvements can easily be seen in infrastructural developments across Colombo including roads, shopping centres, restaurants, public spaces such as parks, pavements and redeveloped buildings / heritage sites. Whilst the State has won much praise for the new infrastructure, the dark side of the infrastructural development in Colombo has not been well-documented or publicised, so there is a lack of social awareness surrounding issues such as land acquisition and the loss of communities, cultures and lifestyles. With this in mind I attended a café discussion called ‘The City and its People: Documenting the changing landscape’ organised by the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) which featured 3 keynote speakers talking about the ways in which they document the changing city landscape so that social history is not lost within the current drive for modernisation.

Chandragupta Thenuwara

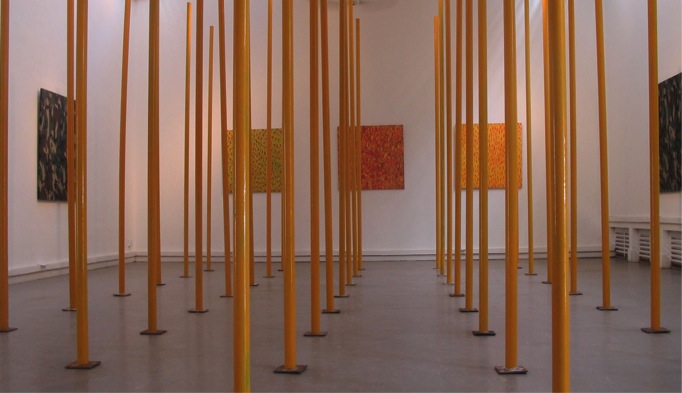

Chandragupta Thenuwara was the first speaker, a well-known artist in Sri Lanka whoportrays the environmental and social effects of the highly centralised military-led development through his art installations. His presentation explored the messages in his work, in particular his work depicting the militarisation of space through ‘camouflage’, such as painted barrels, and other symbols of state control within society.

Chandraguptha Thenuwara, Barrelscape, 1998, Painted barrels arranged on the road.

Chandraguptha Thenuwara, Neo barrelism, 2007 Installation with painted PVC yellow pipes, Lionel Wendt gallery, A view of the exhibition ‘neo Barrelsim’.

“The barrels block my view”. The stimulus behind Thenuwara’s ‘Barrelsim’ came from the armed conflict in Sri Lanka which saw the landscape heavily transformed by the use of barrels. Thenuwara explored the presence of the barrel through his artwork, expounding it was not a neutral object, but one loaded with connotations of power, subjugation, and ethnic division. Thenuwara’s work has continued to explore society, ethnicity and (urban) landscapes through the medium of camouflage, such as camouflaged barbed wire imagery which has become a powerful symbol representative of internally displaced people (IDP) camps and deep-rooted ethnic issues such as the politics of inclusion/exclusion based on ethnicity, and ethnic identities.

Photo courtesy Vikalpa

Photo courtesy Vikalpa

Thenuwara’s most recent installation at the Lionel Wendt explored the ‘beautification’ of urban areas. The ‘Beautification’ installation used the gallery space to critique Sri Lanka’s post-war urban development strategy of ‘beautification’ (through the military), which according to Thenuwara has created dehumanised sterile spaces with no traces of the past, communities, or culture. Thenuwara’s compelling argument is that beautification is the new camouflage.

Priyanthi Fernando

The second speaker was the Executive Director at Centre for Poverty Analysis, Priyanthi Fernando. For years Priyanthi has done what many in Sri Lanka are too afraid to do, and taken to the roads by bicycle or on foot, documenting the ‘before and after’ changes in the city on camera. The photo focusing on the loss of land, livelihood and homes of the Dhobi (washermen) community highlighted the need to not just document, but also preserve the cultures that are almost being washed away by the new facelift Colombo is having.

Bulldozed area in Perahera Mawatha, where the Dhobi community used to reside. The remains of a Kovil can be seen on the left.

The area the Dhobies have been relocated

Some communities that have been forcibly evicted have been relocated, others have not. The Dhobies are amongst those to have been relocated, and the above photograph depicts their new location on Nawam Mawatha, away from the main road and the ‘eyes of passers-by’. The Dhobies consider their new location to have relatively good facilities, however worry due to the temporary nature of the situation, saying that in 2 years they will be forced to move again, but are unsure as to where. Living with this type of uncertainty can fuel tensions or lead to stress, anxiety and other negative consequences so is undoubtedly an area in need of addressing.

Abdul-Halik Azeez

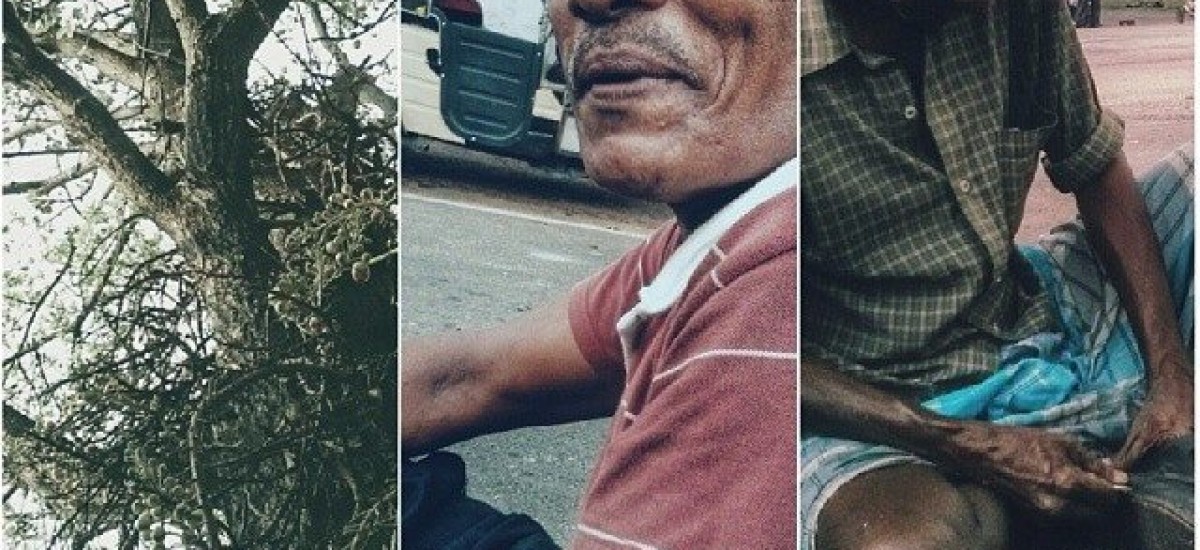

Finally, the third speaker, Abdul-Halik Azeez (@ColomBedouin on Instagram), spoke about the augmentation of #instameetSL, a group from Colombo who use Instagram to document and preserve the changing city environment from multiple perspectives. The presentation focused on pictures recording the areas of Pettah market and Maradana Railway Station, some featuring houses part-way through demolition, and others focusing on people, with Abdul bringing the photos to life by telling the stories behind them (see below).

“I was taking a picture of this tree when Dassanayake (center) politely told me not to. It was a sacred tree he said. I think he said it was a Sal tree. Sal flowers are very popular to place in worship of the Buddha, he said, people from all over seek this tree out for its produce. Apparently it is particularly effective in helping out couples trying to have children. Dassanayake is a practicing Buddhist, but he speaks fluent Tamil with the Abans cleaning lady close by, he drives a truck for the same company. His taciturn shoe-repairman friend, a Christian, sat under the same tree minding his own beeswax. The tree is located right outside the Asiri hospital. You find many interesting people here making a living out of the cracks in the economy of Colombo’s emerging new upper middle class who are increasingly laying claim to the city. Just a few moments before I met Saman, who is a ‘rent-seeking’ unsanctioned ‘parking assistant’. He will help you park, trusting you to tip him for a service you at times do not even require. Business must be good though, because Saman has been at it for 18 years. Colombo is changing though and increasingly people like Saman and Dassanayake’s friend are finding it hard to eke out a living. Many informal entrepreneurs like them have been cleared out of the city as the government pushes forward a beautification project to turn Colombo into something like Singapore. Saman politely asked not to be photographed because he didn’t want trouble. A TV crew interviewed him a while ago and he got all the wrong kind of attention as a result. Survivors have to keep low key I guess.

Please tag your photo narratives about changing Colombo under the hash tag #ChangingColombo Add #ContemplatingIndependence if you’re also exploring thoughts of ethnic harmony and ‘freedom’ #Colombo #SriLanka #Development #StreetPhotography”

Concluding Remarks

The presentations ran into discussions ranging from the necessity of citizen empowerment to challenge undemocratic forms of urban development, to the lack of social awareness within certain sectors of society due to the notable absence of publicised information on the issues of relocation and land acquisition processes.

It would seem the infrastructural improvements, which have primarily been carried out by the military, have taken place in a highly centralized manner with little evidence that the poor are either consulted or are intended as beneficiaries. The planning process has resulted in many of the poorer citizens being relocated, losing their homes or, in many instances their businesses, communities and livelihoods. This trend is going to continue to play out across Colombo, and indeed Sri Lanka, so whilst preserving history, cultures and communities through documenting changes is imperative, further research and awareness raising is crucial to mitigate the negative impacts on the country’s poorer citizens, and ultimately inform urban development policy.

On a final note, it would strongly appear post-war reconciliation and reconstruction are intimately bound together in Sri Lanka. Though much scholarly work on reconciliation is preoccupied with Western notions of reconciliation as a process based on forgiveness, healing and coexistence, Wilson (2003) indicates the reconciliation process is better thought of as an attempt, in transitional phases, to “legitimize tarnished state institutions”. This notion can be applied to Sri Lanka and also be said to characterise the Sri Lankan state’s motivations in the LLRC process. However, as became evident during the ceasefire period (2002-2006) in Sri Lanka, the prioritisation of economic development programmes does not provide long-lasting, sustained peace in the absence of an open society and political stability (Holt 2011). To prevent the resurgence of further conflict the grievances of both the low-income groups in Colombo and the minority groups in the North and East need to be adequately addressed in a meaningful manner.

References

- Bopage, L. (2010), Post-War Sri Lanka: Way Forward or More of the Same?, Ground Views, 23rd May, available at http://groundviews.org/2010/05/23/post-war-sri-lanka-way-forward-or-more-of-the-same/

- Goodhand, J. (2001) Sri Lanka in 2011: Consolidation and Militarization of the Post-War Regime, Asian Survey, Vol. 52, No. 1, pp. 130-137

- Holt, S. (2011), Aid, Peacebuilding and the Resurgence of War: Buying Time in Sri Lanka, (Palgrave Macmillan)

- Wilson, R. (2003), Anthropological Studies of National Reconciliation Processes, Anthropological Theory, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 367-387