The President enters Twitter

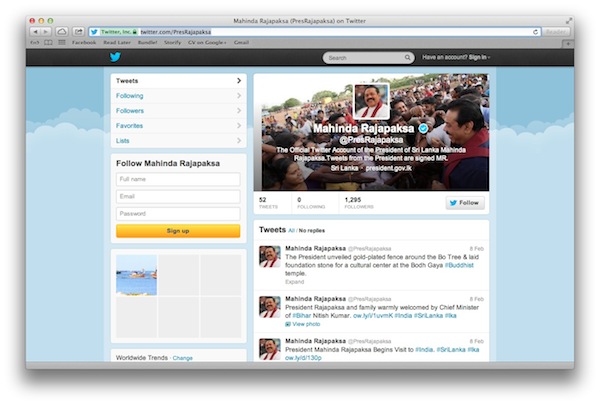

Last month, the President of Sri Lanka began tweeting officially as @PresRajapaksa. The account is already authenticated by Twitter. Though @PresRajapaksa’s profile notes that “tweets from the President are signed MR.” there is, to date, not a single tweet penned by the President himself.

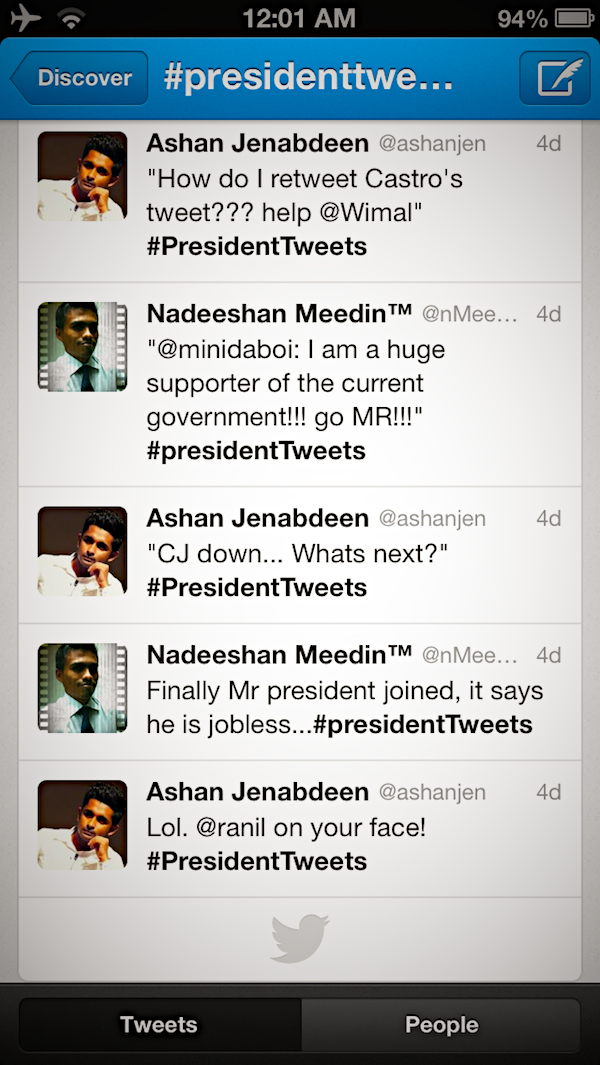

The launch of the account was instructive in how the regime is perceived online by voices not usually openly vocal about mainstream politics. Under the hashtag #PresidentTweets, dozens of voices on Twitter openly poked fun at the President’s entry to Twitter. The tweets, only a fraction of which are captured below, poked fun at the President’s closest political associates, his role in the impeachment of the Chief Justice, his violent, autocratic tendencies and the Rajapaksa family’s nepotism.

An inauspicious start then to what objectively is a welcome development – the entry of the President to a medium that is now used by so many leading political figures around the world. For those reliant on Twitter to disseminate critical content that cannot be published or archived anywhere else can also take hope in the fact that once official propaganda embrace social media, it is far less likely that these platforms and tools will be blocked or access disrupted.

The competition

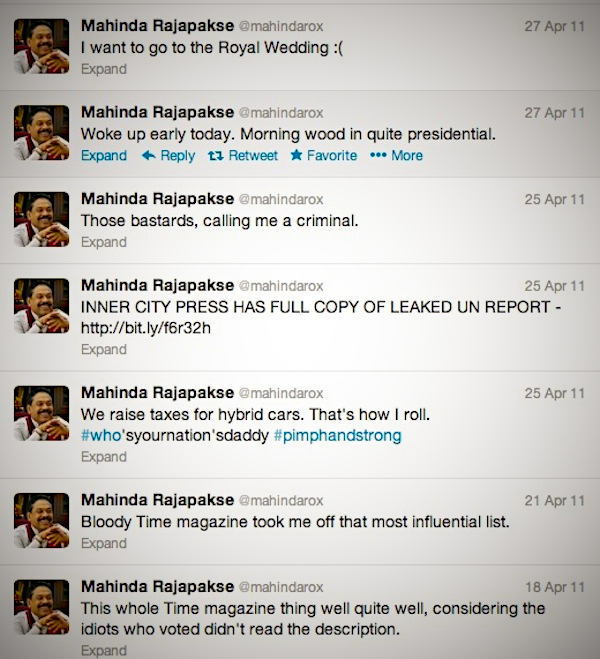

Any keen observer of social media in Sri Lanka would lament that the President’s real account is far less interesting and entertaining than the now discontinued @mahindarox on Twitter, very active over 2011.

The brains behind the tweets

@PresRajapaksa (and ostensibly, the President’s official Facebook page) is the brainchild of the soi-disant International Media Director Anuradha Herath (who was formerly the head of the Sri Lanka College of Journalism), who now sits at the President’s Office and tweets as @AnuradhaKHerath. Groundviews was reliably informed that she and a small team based in the President’s Office are now in the process of assembling an online / new media propaganda team. Over 2013, it is very likely this team will spearhead operations that fully embrace the significant and pervasive disinformation and misinformation capabilities of new media to help the Rajapaksa regime discredit and dismiss legitimate criticism, as well as, through various means, drown out critical content and voices.

Interestingly, we understand some bloggers and noted voices in online fora who have acceded to requests to meet at Temple Trees have done so out of fear, whereas others, it is clear, are quite pleased to be associated with and working for the regime. It isn’t clear whether this Faustian service involves any material or financial compensation.

The Rajapaksa government is already hugely adept at architecting and condoning violence against journalists physically and with complete impunity. This year will see their efforts strategically embrace online means as well.

Evasion online

Though perhaps infrequent, it is clear the President is shown activity on his Twitter profile (which may include tweets addressed to him).

President Rajapaksa looked through his official Facebook and Twitter pages today during lunch. #lka #SriLanka

— Mahinda Rajapaksa (@PresRajapaksa) January 22, 2013

However, neither the official account of the President nor its curator, Anuradha Herath, engage with inconvenient questions, such as those posed to both by Sri Lanka’s BBC correspondent Charles Haviland.

Black posters/black headbands remembering journos killed/exiled/ disappeared which puts #SriLanka near bottom of world media freedom table.

— Charles Haviland (@cfhaviland) January 29, 2013

@cfhaviland Seriously, why don’t you talk to @anuradhakherath in her official capacity to ascertain how @presrajapaksa defends this? #lka

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 30, 2013

(1) @groundviews @anuradhakherath @presrajapaksa Anuradha/Prez, no one’s brought 2 book over journalist deaths/abducs. In case of Lasantha..

— Charles Haviland (@cfhaviland) January 30, 2013

(2) @groundviews @anuradhakherath @presrajapaksa ..in Lasantha case a young Tamil man was held a long while & died in custody. Campaigners..

— Charles Haviland (@cfhaviland) January 30, 2013

(3) @groundviews @anuradhakherath @presrajapaksa .. ask why proper charges aren’t brought in such cases. Wd be grateful for response. Thanks

— Charles Haviland (@cfhaviland) January 30, 2013

The use of the President’s Twitter and Facebook accounts are rather revealing too, and suggest strategic cunning behind their curation. For example, the statement after the President’s meeting with Bodu Bala Sena was disseminated only in English – the full statement via the President’s Facebook account and four associated tweets.

Bodu Bala Sena Meets President Rajapaksa. Full release on Facebook: ow.ly/hadJL ow.ly/i/1qDuY (Part 1/3)

— Mahinda Rajapaksa (@PresRajapaksa) January 27, 2013

President Rajapaksa requested Bodu Bala Sena not to engage in any activities that would be seen as promoting communal hatred. (Part 2/3)

— Mahinda Rajapaksa (@PresRajapaksa) January 27, 2013

President: It’s OK to work to strengthen Buddhism, but it should be done without creating conflicts with other religions. (Part 3/3)

— Mahinda Rajapaksa (@PresRajapaksa) January 27, 2013

To reiterate, there was no Sinhala or Tamil translation of the official statement at the end of the meeting made available on any official website, including the President’s Facebook account, or tweets in Sinhala or Tamil. Given that the growing and disturbing Islamophobia in Sri Lanka is generated predominantly in Sinhala, it is curious as to why the President’s Office didn’t want to publicise the meeting’s outcomes in a language other than English.

Compare this to Twitter coverage of the meeting with Australia’s Deputy Leader of the Opposition Julie Bishop, who in subsequent statements upon her return home reveals a clear pro-Rajapaksa regime bias.

PHOTO: Australia’s Deputy Leader of the Opposition Julie Bishop called on President Rajapaksa. ow.ly/i/1scbe #lka #SriLanka

— Mahinda Rajapaksa (@PresRajapaksa) February 1, 2013

?????? ??????????? ?? ???????? ??? ????????t? ???????? ?????? ??????? ???????? ??? ???????????. ow.ly/i/1sfca #lka #SriLanka

— Mahinda Rajapaksa (@PresRajapaksa) February 1, 2013

???????????? ????? ????? ???? ???? ???????? ???????? ??????????????? ?????????? ???????????. ow.ly/i/1sfca #lka #SriLanka

— Mahinda Rajapaksa (@PresRajapaksa) February 1, 2013

It is evident therefore that the President’s new media presence isn’t seen as a vehicle of engagement with society and polity, but rather, an extension of his government’s policy to pass off propaganda and partisan perspectives as news and official updates.

Complete archive

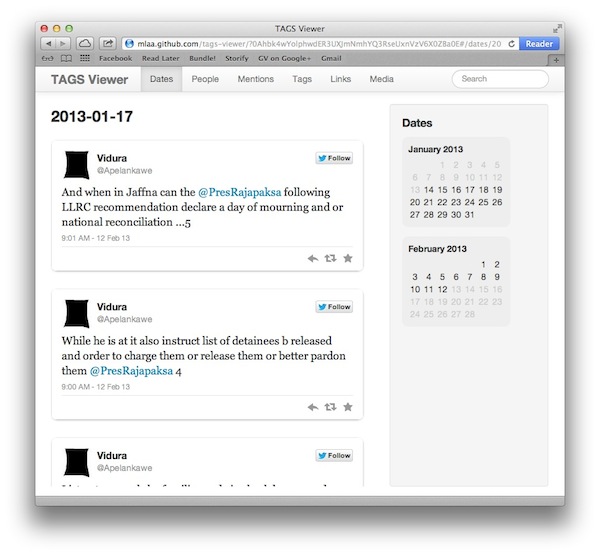

Because of what’s stated as well as the damning silences and evasion, Groundviews felt it imperative to record for posterity all the tweets published by @PresRajapaksa as well as all interactions referencing this official account, starting from Day One.

Groundviews is pleased to present a novel and easy to use front end to a comprehensive archive, constantly updated, of the President’s interactions and content generation on Twitter.

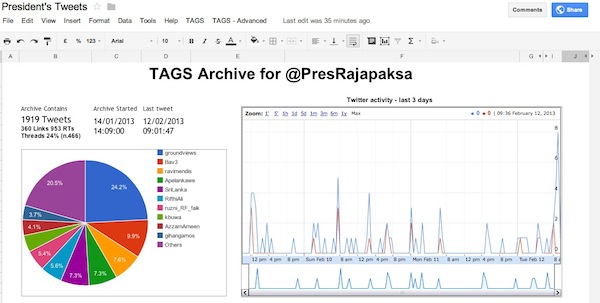

To see all the tweets (updated daily) access the full spreadsheet here.

There is also a data visualisation giving top-level information about @PresRajapaksa accessible here. Though the screenshot of the dashboard below is accurate at the time of publication, the link will always open a page with updated statistics.

Propaganda 2.0 by the Rajapaksa regime

Given what Groundviews knows about the capabilities of the new media team at the President’s office, and the overarching (electronic/communications) surveillance architecture at the command of the State, we tweeted the following as an advisory to civil society activists.

1. Heard @anuradhakherath‘s assembling v. interesting group of bloggers/new media voices in support of @presrajapaksa & Govt #lka #srilanka

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 28, 2013

2. Told 2 meetings already held at Temple Trees. @anuradhakherath using knowledge from stint at @slcj_journalism for Prez. #lka #srilanka

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 28, 2013

3. Inter alia, @anuradhakherath‘s initiative marks new chapter in dis/misinformation & propaganda campaigns online. #lka #srilanka

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 28, 2013

4. It can be expected that @presrajapaksa regime will increasingly use social media to counter int. condemnation & pressure #lka #srilanka

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 28, 2013

5. Pro-democracy, HR, media activists should take note. Propaganda 2.0 will be sophisticated, pervasive, persuasive, good. #lka #srilanka

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 28, 2013

Aiding the regime’s increasingly competency and strategic use of new media is (domestic) civil society’s ignorance of its potential and reach. New media knowledge is poor, at best, especially at senior management levels in almost every single NGO working on human rights and media freedom issues. Many senior activists – those at the forefront of street demonstrations – remain new media illiterate. Many NGOs are seriously behind government in leveraging new media for advocacy and activism. At best, web platforms are merely used to promote and feature the tired real world activism amongst and by the usual suspects, which really is to miss the point about the reach, virality, creativity and potential of web based media and campaigns.

Though there is no way whatsoever of accurately foretelling how and to what ends the government will leverage its increasingly sophisticated use of new media, several obvious challenge arise as a consequence for dissent groups and individuals, including independent web based media and journalists.

Pro-Govt content creation: Silencing through volume

A group of say around 15 distinct voices (on Facebook, Twitter, blogs, Flickr, YouTube) can, for example, effectively and efficiently subsume vital updates from civil society (e.g. from @vikalpasl, @groundviews on Twitter) by just putting up content with greater frequency. All web based social media is irascibly ephemeral – relentlessly bombard each platform with sophisticated, believable propaganda and the real stories are lost in the melee. The government has plausible deniability, and the chilling effect of being perennially subject to vicious attacks by anonymous as well as openly pro-regime identities online can serve as significant barriers to civil society collaboration and output.

Shaming, and the threat of shaming

Coupled with hacking, detailed below, personal, institutional and family secrets can be used to blackmail prominent voices to retract earlier stories or cower into silence. The culture of over-sharing online – including location data, travel, meeting and other personal updates – lends itself to authoritarian regimes which can take advantage of civil society’s poor understanding of privacy and security settings to listen in, monitor, build up personality, financial, activist, meeting and movement profiles.

Another new threat vector is to infiltrate personal (web based) social networks through the less protected accounts of friends and children. An example could be a politically apathetic yet good friend of a civil society activist or a teenage family member, who is relatively careless about good Internet and web security. It is fairly easy to hack into this person’s account, which then provides easy backdoor access to most activities and updates of the intended target even if they are accounts closed to the larger public. The primary objective here is to listen in rather than to disrupt. Again, information gathered can be used in any number of ways – from identity theft to the threat of hate, hurt or harm to close members of family with a view to silencing dissent.

Hacking and Denial of Service attacks

The websites of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (serving as the institutional anchor of Groundviews), Groundviews itself and Vikalpa (our sister site) have since December 2012 faced unprecedented levels of hacking attempts, numbering in the dozens each day, from technically savvy individuals or groups, whose geographic point of origin cannot be easily traced. While it is emphatically not the case that, at least to date, Anuradha Herath or the President’s office of Sri Lanka are assembling group of hackers against local and international dissident groups, it would be logical to invest in such capacities – following the likes of the former Tunisian and Egyptian regimes, and the current Syrian regime – if the government wanted to thwart growing civil society output online. It may also be the case that whatever group that is assembled under the blessings of Temple Trees, out of greater patriotism or ambition (or just too much arrack on any given evening), takes it upon themselves – without any directive from a higher authority – to engage in hacking attempts on sites they see fit to silence, deface or delete.

Existing surveillance architectures covering voice and data across multiple channels and platforms can also be leveraged to silence dissent, an easy enough task with State and private telcos unwilling and unable to stand up robustly for the privacy of customers in the face of extra-legal governmental edicts and Ministry of Defence demands.

Coupled with outright blocks of websites and physical threats to content creators / journalists / civil society activists and the hate speech they already endure through more traditional media channels, the landscape for online output of critical dissent is going to get more challenging than it has ever been in Sri Lanka.

Meeting this challenge is not impossible, but will require every single individual and institution working on Sri Lanka’s democracy, governance, rights and accountability frameworks (in the country and outside) to emphasise – more than ever before – new media safety, security and innovative content generation strategies for online fora.