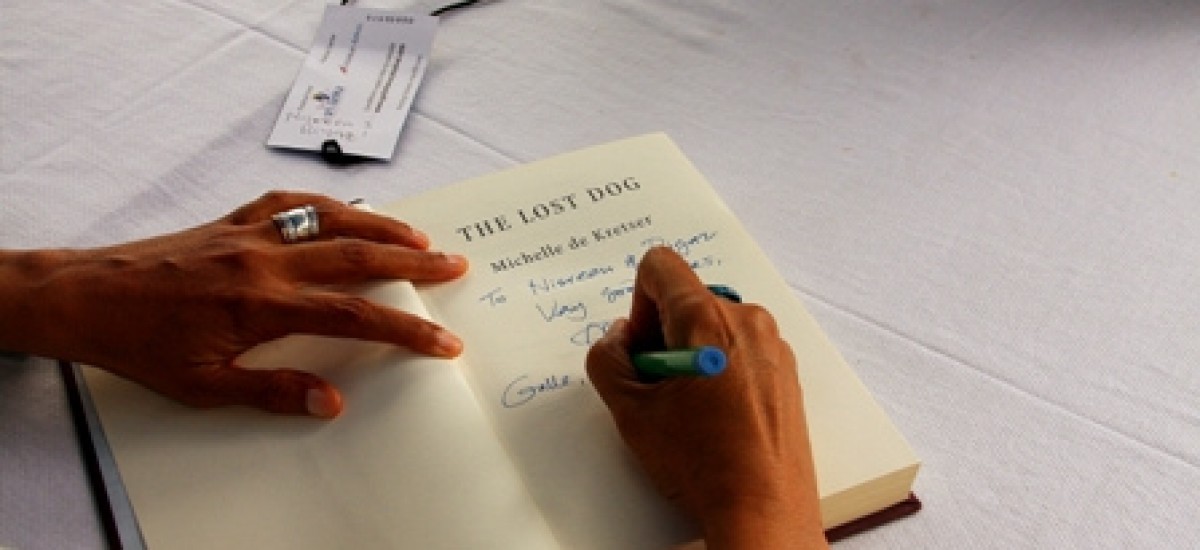

Michelle de Kretser signing. Photo by Sharni Jayawardena, courtesy Galle Literary Festival

The Editors of Groundviews received via email this morning intimation of an international appeal made by Reporters Without Borders and Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka (JDS), a network of exiled Sri Lankan journalists. The Galle literary festival appeal notes inter alia,

“We believe this is not the right time for prominent international writers like you to give legitimacy to the Sri Lankan government’s suppression of free speech by attending a conference that does not in any way push for greater freedom of expression inside that country.”

Now in its fifth consecutive year, the Galle Literary Festival has been called many things, but a ‘conference’ it has not. Things go inexorably downhill from here. This ill-advised appeal reminds us of the equally ill-conceived Amnesty International human rights campaign during the last cricket world cup in 2007. At the time, even well-known human rights defenders in Sri Lanka wrote against AI’s campaign. As The Amnesty Campaign: Taking the Eye Off the Ball by Dr. Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu noted,

“The full extent of the impact and damage of this campaign is yet to be seen. One hopes that public discourse on human rights protection in Sri Lanka is not going to be irretrievably obscured and obfuscated by reference to the rights and wrongs of this campaign or that Sri Lankans will in any way be deterred from lending their voice to the urgent need for human rights protection in this country, by concerns about being unpatriotic that have been aroused by memories of this campaign. The Amnesty campaign has been clumsily and insensitively conceived. It as made an issue of itself in Sri Lanka and detracted attention from the issue in Sri Lanka it rightly sought to draw attention to.”

Another pseudonymous writer on Groundviews (Amnesty Campaign: Some quick thoughts) and the vast majority of commentators on both articles concurred on how myopic AI’s campaign was. Few, if any, discounted that human rights protection in Sri Lanka was a serious challenge, and that the government had largely failed in this regard. Many however were strongly opposed to how AI chose to go about flagging it. The RSF/JDS campaign tragically revisits the fiasco. The bizarre appeal attempts to peg what are indubitably serious and real concerns over media freedom to a festival of literature that has nothing to do with media or journalism. It is unclear what if any consultation there was with local media freedom activists and groups before this appeal was launched. We could not find similar appeals by RSF to stay away from the Jaipur Literature Festival over India’s human rights violations in Kashmir and elsewhere within its borders, as Arundhathi Roy, a signatory to this appeal, knows better than most.

We also wonder why this appeal is issued now, in 2011? GLF began during war, and continued throughout it. Reflecting this, GLF sessions proper, as well as a number of fringe events over the years, have addressed issues of media freedom and the freedom of expression. At the 4th GLF, fringe panels included interesting discussions on what post-war literature and writing would be like, what issues they would address and how. At the 3rd GLF, a fringe event brought together a senior government spokesperson from the Presidential Media Unit as well as other journalists to talk about what even at the time was a fairly bleak outlook for media freedom. At its core, GLF is embodies precisely what RSF/JDS often advocate – a space for critical enjoyment of the written and spoken word and a platform for the celebration of ideas. If writers boycott the festival, so will international media. And if international media boycotts the event, how can they report on the challenges facing mainstream media when compared to the freedom of expression in the festival? As Lindesay Irvine said in the Guardian in 2009,

“All of this marvellously free expression struck a distinctly uneasy note, knowing that one of the world’s bloodiest civil wars was being played out on the other side of the island, with thousands of civilians trapped between the Sri Lankan army and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, the world’s press kept away and local journalists all too aware that to report anything other than the government’s propaganda is to put your life in peril. (I should stress here that both sides of the Sri Lankan civil war are very careful not to endanger western tourists, and visitors to the southern half of the island are at no tangible risk. They need your money. Go.)”

Each GLF brings with it more, not less scrutiny on the country’s media landscape. It keeps Sri Lanka on the international media’s map, when in fact it rarely is now that the war is over. The festival’s curator, Shyam Selvadurai, is an award winning Tamil author. Any charge that he is insensitive to the complex politics of conflict and violence is one that simply does not stick. His recent interview featured on Groundviews suggests a festival that is popular and keenly anticipated, locally as well as internationally. As for not dealing with more contentious issues related to war, the BBC World Forum is organising as part of the official programme a session moderated by the outspoken, award winning human rights and media freedom activist Sunila Abeysekara on how displacement continues to affect the Sri Lankan psyche almost two years after the end of the civil war. The panel also features Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie who explores the lasting effects of Nigeria’s 1960s civil war through some of her stories in The Thing Around Your Neck. Perhaps this escaped the attention of RSF and JDS.

Groundviews and Vikalpa have borne witness to Sri Lanka’s atrocious record of media freedom since their inception, including on Lasantha and Prageeth. RSF/JDS find it “it highly disturbing that literature is being celebrated in this manner in a land where cartoonists, journalists, writers and dissident voices are so often victimized by the current government.” The concern over the deterioration of media freedom is fully shared. How to address it is emphatically not. If GLF celebrates literature, that alone is reason enough to support it, attend and expand as much as possible the idea of the festival to other locations in Sri Lanka and in the vernacular to boot. If it is the case that the freedom of expression within GLF is absent from mainstream media, then the remedy is surely to not boycott the one instance where it is actually present?

The appeal ends by noting that “unless and until the disappearance of Prageeth is investigated and there is a real improvement in the climate for free expression in Sri Lanka, you cannot celebrate writing and the arts in Galle”. In fact, it’s also investigations into Lasantha’s murder that we need to be concerned about. Sustained emphasis on both cases in particular and the serious challenges facing media freedom in general, however, does not justify a boycott of GLF. In not recognising the symbolic value of an event where during war and after it, the freedom of expression is actively encouraged, RSF and JDS undermine their own appeal.

Events like GLF are sadly rare. Let us enjoy them in peace.

[Update, 24 January 2011: Also read Writing against the RSF/JDS appeal to boycott the Galle Literary Festival, by Sunila Abeysekara.]