My daughter Dhara, 13, finds it incredible that I had never seen a working television until I had reached her current age — that’s when broadcast television was finally introduced in Sri Lanka, in April 1979. It is also totally inconceivable to her that my entire pre-teen media experience was limited to newspapers and a single, state-owned radio station.

And she simply doesn’t believe me when I say — in all honesty and humility — that I was already 20 when I first used a personal computer, 29 when I bought my first mobile phone, and 30 when I finally got wired. In fact, my first home Internet connectivity — using a 33kbps dial-up modem — and our daughter arrived just a few weeks apart in mid 1996. I have never been able to decide which was more disruptive…

Dhara is growing up taking completely for granted the digital media and tools of our time. My Christmas presents to her in the past three years have been a basic digital camera, an i-pod and a mobile phone, each of which she mastered with such dexterity and speed. It amazes me how she keeps up with her Facebook, chats with friends overseas on Skype and maintains various online accounts for images, designs and interactive games. Yet she is a very ordinary child, not a female Jimmy Neutron.

Despite my own long and varied association with information and communication technologies (ICTs), I know I can never be the digital native that Dhara so effortlessly is. No matter how well I mimic the native ‘accent’ or how much I fit into the bewildering new world that I now find myself in, I shall forever be a digital immigrant.

It was Marc Prensky, an American author, education reformer and learning game designer, who in 2001 coined the term ‘digital native’ to describe a person for whom digital technologies already existed when they were born, and have therefore grown up ‘being digital’. The term draws an analogy to a country’s natives, for whom the local culture, language and folkways are natural and indigenous. In contrast, digital immigrants are those born and raised elsewhere (in this case, in the analog era), and arrived in digital-land later on in life.

Prensky refers to common traits among digital immigrants, such as printing documents rather than commenting on screen or printing out emails to file in hard copy form. Digital immigrants are said to have a “thick accent” when operating in the digital world in distinctly pre-digital ways, when, for instance, he might phone someone to ask if an email was received.

In a 2005 essay titled ‘Listen to the Natives‘, Prensky said: “Schools are stuck in the 20th century. Students have rushed into the 21st. How can schools catch up and provide students with a relevant education?” Note he was referring to the education system in the United States — the home of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, and where the global Internet was born 40 years ago.

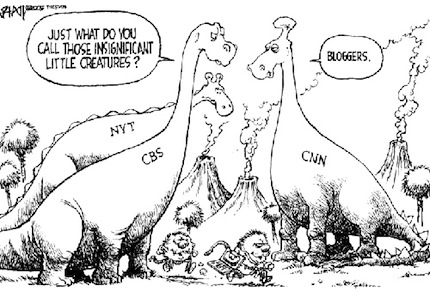

Mediasaurus?

On the other side of the planet, we can ask a similarly probing question about the mainstream media in Sri Lanka. While the people formerly known as the audience have moved into the 21st century, most of our mainstream media are lagging years or decades behind. Not so much in technology, but in mindset. Some media proprietors, as well as many senior editors and journalists, have yet to become digital immigrants even reluctantly. They stubbornly cling on to an analog past, and are neither prepared nor equipped to relate to the digital age. Can they be effective watchdogs or opinion leaders of our times?

In August this year, I addressed a gathering of media owners, publishers, editors and senior journalists — almost all of them working in the mainstream print or broadcast media in Sri Lanka. The occasion was the Sri Lanka launch of Asia Media Report 2009, held at the Galle Face Hotel in Colombo. I posed to them some difficult questions: at a time when the mass media as we know it is under threat of mass extinction, what must our media do to survive? Do most of our media deserve to survive? Or have they outlived their purpose?

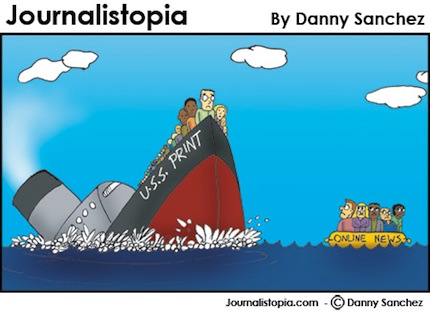

In answering these, I cautioned my audience that if they continue business as usual, they cannot expect to remain relevant, or even solvent, for too long. I almost called them dinosaurs, and compared their industry to the supposedly unsinkable Titanic.

Let me explain. In October 1993, the American science fiction and thriller writer Michael Crichton wrote a landmark essay in Wired magazine titled “Mediasaurus“. In this essay, he prophesied the death of the mass media. He wrote: “To my mind, it is likely that what we now understand as the mass media will be gone within ten years. Vanished, without a trace.”

Crichton knew a thing or two about dinosaurs: he wrote Jurassic Park and sequels, which later became blockbuster movies. Only those nimble, adaptable media products would survive, he said. The rest would be wiped out by new technologies that helped readers and audiences customise what they want. Audiences will abandon the media anyway, he said, because they found media delivering less and less value to pay for it.

It took much courage and foresight to say this at a time when the World Wide Web was in its infancy, and the mainstream media (MSM for short) still ruled the newsstands and airwaves. But Crichton saw it coming, even if his timeline was a bit off, by half a dozen years. When he died in November 2008, the newspaper and broadcast industries on both sides of the Atlantic were in major crisis, shedding staff, circulation, audiences and revenues. The business models that had worked for decades or centuries were no longer viable. The global economic recession was dealing knock-out blows to media groups who had failed to adapt to the new realities.

The situation is not so grim in many parts of Asia, where there still is considerable vibrancy in the media industries. Some suggest that Asia is enjoying the world’s last great newspaper boom. Eight of the world’s 10 largest circulating, paid-for daily newspapers are in Asia, which now has the largest national newspaper markets (China, India and Japan). In radio and television broadcasting, too, there has been an explosion of channel numbers in the past two decades. Our region is now home to the biggest broadcast audience on the planet.

So are we in Asia somehow shielded from the crisis that engulfs the media in Europe and North America? Not quite. Global developments in media and telecommunications have historically taken years or decades to reach our part of the world. But worryingly, that time lag has been shortening in recent times. Going by this, we can expect the media’s current crisis to arrive at our shores sooner than later. At best, we have just a few years.

But instead of changing course, I see some of our MSM behaving with the same kind of arrogance that doomed the Titanic. In this instance, the deadly iceberg has already been spotted. So should the captains of MSM Titanic be re-arranging furniture on the ship’s deck — or discussing rescue plans instead?

Rocket in your pocket

Two trends that started separately have recently converged to radically change how humans generate, access, store and share information.

- The rolling out of higher-speed, always-on broadband Internet enabled the development of what is collectively known as web 2.0. These second generation web technologies and platforms enhance creativity, information sharing, and, most notably, collaboration among users.

- The newer mobile phones enable easier access to these web 2.0 applications, partially bypassing the need for personal computers. Mobile manufacturers are racing to produce phones that match the processing capability of computers but at a much lower cost and with greater portability.

Earlier this year, we marked the 40th anniversary of the first Moon landing. An estimated 750 million people watched that event live on television in July 1969. An equally important milestone was quietly achieved by a small group of nerds and geeks a few weeks later, and no one noticed it for years. On 2 September 1969, computer scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, established a network connection between two computers — creating the very first node of what we now know as the Internet.

While only a dozen men (yes, all men!) have so far walked on the Moon, nearly a quarter of the world population (over 1.5 billion people) today has access to the web. I recently came across a rather sobering factoid: the most basic mobile phone in use today contains more processing power than did the entire Apollo 11 spaceship that took those first astronauts to the Moon. Just imagine — more than 4 billion human beings are roaming the planet today with tiny gadgets that are more sophisticated than the last generation’s most celebrated triumph of technology.

And that’s only the beginning. Anyone armed with such a mobile phone can, in theory, become an instant reporter or commentator on events unfolding around her. Just how can the professional media come to terms with this reality?

American journalist A.J. Leibling (1904 -1963) once said, “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” In his time, that was perfectly true. In our topsy-turvy times, however, the reverse is increasingly the case.

My British media activist friend David Brewer has just published an online guide on how to become a publisher or broadcaster in 100 minutes using free tools that can be downloaded and activated by any computer literate person. (Okay, the non-geeks among us might need a bit longer than that, but still you can be in business in a few hours.)

We can only speculate where the continuing growth in processing power and the proliferation of ICT devices might lead us (Sir Arthur Clarke, how we miss you!). This can be exhilarating for some — and very disconcerting for others who were previously in control of the free flow of information, such as governments, scholars and, yes, the mainstream media!

MSM have gone from denial to dismissal to apprehension about this murky, distributed phenomenon called citizen journalists (CJ) -– which includes blogs, online petitions, public video platforms and micro-blogging enabled by Twitter. In Sri Lanka, citizen journalism initiatives such as Groundviews and Vikalpa regularly elicit content from ordinary citizens with little or no training in journalism.

The real debate is not about who is, or isn’t, a journalist. We must move way beyond that, and look at how we can strengthen anyone, anywhere who takes up communicating in the public interest. As I said in a recent online discussion concerning one of the world’s top citizen media platforms: “Just as journalism is too important to be left solely to full-time, salaried journalists, citizen journalism is too important to be left simply to irresponsible individuals with internet access who may have opinions (and spare time) without the substance or clarity to make those opinions count.”

Media is a plural!

The political, economic and cultural implications of MSM’s abdication of social responsibilities have been discussed exhaustively by media watchers and researchers. The last phase of the Sri Lankan war, and the first few months of the post-war period, have brought into sharper focus the inadequacies of the mainstream media to serve the mirror, watchdog and platform roles of the media.

Despite all this, I don’t want to write off the mediasaurus just yet.

CJs can help make things better, fill some MSM gaps and make the myriad conversations more inclusive, nuanced and richer. But CJs aren’t a panacea to all that is not right in the mainstream media or paid-for journalism.

In the end, citizen journalists are necessary — but not sufficient. They alone cannot meet all the information and communication needs of the human family that will soon have most of its members connected. We still need what social activists derisively refer to as the ‘Big Media’.

In April 2007, I spent a week in Sydney, Australia, participating in an international conference of media researchers and activists. Meeting in a city that remains a key anchor of mogul Rupert Murdoch‘s global media empire, references to him were inevitable. But I felt we spent too much time and energy demonising Murdoch and his kind, and romanticising the alternatives. Must we always choose between them?

For sure, the Murdochs (and mini-Murdochs who have popped up across Asia) must be held accountable by regulators and consumers. But the answer to the many excesses and lapses of corporate media is not, simply, to aspire exclusively for citizen or community media. We need both kinds.

MSM has always been a glass half full, but that ‘filled half’ holds tremendous value for our societies. I would much rather have imperfect yet pluralistic mainstream media than no media or, heaven forbid, only the state-owned media.

Our challenge is to improve the professional and ethical standards of ALL media — whether public, corporate, community or citizen owned. Media is a plural term, and our world is large enough for all kinds of media to co-exist and jointly serve the public interest. Citizen Kane and Citizen Journalist can complement each other.

Ana-digi hybrids

I used to say I’m exactly as old as Star Trek, but another way to put it is that I am three years older than the Internet. In the eyes of my daughter’s generation, this makes me rather pre-historic, although it has its advantages. Mine will be the last generation to be born entirely analog and die (almost) digital. This digital immigrant status gives us a unique perspective, making us useful navigators and negotiators between the two worlds.

But unless we are careful, we can get lost between these worlds. I sometimes feel like a character in author Jhumpa Lahiri‘s exquisitely woven stories of immigrants from India and their American-reared children — “exiles who straddle two countries, two cultures, and belong to neither”. While I have found my comfort levels in the digital land that I moved to in my 20s, I will always remain an ana-digi hybrid (to coin a phrase).

When I spoke at length on the digital tsunami now sweeping across the media world, some in my Colombo audience last August thought I was advocating everything going entirely online. Actually, I wasn’t. I like to think that both the physical and virtual media experiences enrich us in their own ways.

Two years ago, I finally gave up an entrenched habit of all my adult years: buying a daily newspaper at home. But old habits die hard: I still cherish walking to the neighbourhood boutique every Sunday morning to buy print copies of my favourite weekend newspapers. I might occasionally complain that Sunday reading is not what used to be (ah, the good old days!), yet my Sundays are incomplete without the rustle of newsprint and the smell of printer’s ink.

Call me an ink addict, a digital misfit or whatever you like. The day a computer can deliver not just the information but the full sensory experience of browsing through a Sunday newspaper, I will fully migrate online.

Trained as a science writer, Nalaka Gunawardene has been associated with print and broadcast media for over 20 years. He has been a news reporter, feature writer, op ed essayist, radio presenter, TV host, documentary producer and journalist trainer. He continues to juggle many of these roles, while also blogging, tweeting and occasionally moonlighting as a media researcher and conference speaker. This article written to mark 1000th post of Groundviews.