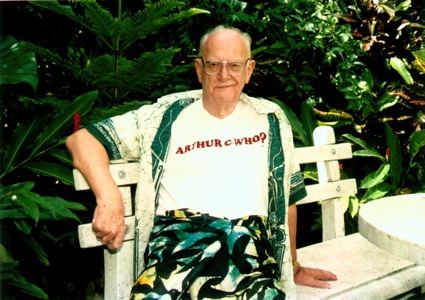

Sir Arthur C Clarke on Hikkaduwa beach, photo by Rohan de Silva

Sir Arthur Clarke’s first death anniversary falls on 19 March 2009

Sir Arthur’s 90th birthday reflections (effectively his public goodbye) is available online at:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3qLdeEjdbWE&feature=channel_page

During his illustrious career spanning over 60 years, Sir Arthur C Clarke received a large number of honours, awards and accolades from scientific, academic and literary bodies worldwide. At one time or another, he won all the top science fiction literary awards. He received honorary doctorates from universities in the east and west. In 1998, Queen Elizabeth II knighted him for his ‘services to literature’.

In his adopted homeland of Sri Lanka, where he lived 52 of his 90 years, he received both the highest presidential honour for science (Vidya Jyothi, 1986) and the highest civilian honour (Lankabhimanya, 2005). The current government marked his 90th birthday with a presidential ceremony graced by visiting astronauts and dignitaries from several space-faring nations.

At the time of his death on 19 March 2008, Sir Arthur also had an asteroid, dinosaur species and a geostationary communications satellite (as well as that entire orbit) named after him. Two nations (Sri Lanka and Palau) had put his image on postage stamps –- a rare honour for living persons.

How can we add to this already stellar list to cherish the memory of Sir Arthur? Would naming Sri Lanka’s first satellite (as recently announced) be a fitting tribute? Or should a monument be better rooted on the Lankan soil, where people can see and feel its presence everyday? Or, do we really need any physical monuments to remind us of his legacy?

As we mark Sir Arthur’s first death anniversary, it is a good time to reflect on such legacy issues. Having worked closely with Sir Arthur during the last 21 years of his life, I can offer some insights on his own thinking and preferences in this respect.

Despite his well known ego, Sir Arthur never sought personal edifices to be put up in his honour or memory. When a visiting journalist once asked him about monuments, he said: “Go to any well-stocked library, and just look around…”

He knew his place in history was well assured by his ideas and imagination expressed in his output of over 100 books, 1,000 essays and short stories, as well as numerous radio and television appearances. He achieved iconic status not just in literature, science and technology, but also in popular culture –- the latter largely thanks to the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Remember as a writer

In December 2007, on the eve of his 90th birthday, I helped Sir Arthur to record a short video message on his life and times. (It turned out to be his public farewell.) He always placed a premium on brevity, and in this video, he allowed himself a minute for every decade he’d lived — a total of 9 minutes. In those 540 seconds, he both looked back at his extraordinary 90 orbits around the Sun, and also cast a wistful look at the future of his island home, planet Earth and the universe.

Sir Arthur listed three last wishes: a sign of life elsewhere in the universe; clean energy replacing oil and coal; and lasting peace in Sri Lanka. Although he didn’t live to see any of these come true, their realisation remains the ultimate ‘Clarke Challenge’. Some of the best minds on the planet are working on the first and second; the government of Sri Lanka believes it is on the verge of achieving the third.

It was in the last two minutes of the video that Sir Arthur touched on posterity. He said: “I’ve had a diverse career as a writer, underwater explorer, space promoter and science populariser. Of all these, I want to be remembered most as a writer –- one who entertained readers, and, hopefully, stretched their imagination as well.”

To end his message, he quoted Rudyard Kipling:

“If I have given you delight

by aught that I have done.

Let me lie quiet in that night

which shall be yours anon;

And for the little, little span

the dead are borne in mind,

seek not to question other than,

the books I leave behind.”

In the weeks and months following Sir Arthur’s death, many have asked me what kind of monument was being planned in his memory. As far as the Arthur C Clarke Estate is concerned, there is none –- and that seems to surprise many.

Yet it is fully consistent with the man of ideas, imagination and dreams that Sir Arthur Clarke was. Monuments of brick and mortar — or even of steel and silicon — seem superfluous for a writer who stretched the minds of millions. Commemorative lectures or volumes cannot begin to capture the spirit and energy of the visionary who invented the communications satellite and inspired the World Wide Web.

Next Arthur Clarke?

Instead of dabbling in these banalities, Sri Lanka should go for the ‘grand prize’: nurturing among its youth the intellectual, cultural and creative attributes that made Arthur C Clarke what he was. In other words, we must identify and groom the budding Arthur Clarkes of the 21st century!

Some might argue that Sir Arthur was a unique product of his times, and they are right. But how did the farm lad from rural England grow into one of the greatest Britons of the 20th century, and become one of the top 10 most influential aerospace thinkers of all time?

Sir Arthur used to joke that one secret of his success was his careful choice of parents (another was never learning the rules of chess!). More seriously, what roles did family, education, peers, travel and social interactions play in producing the distinctively Clarkian combination of sharp wit, irreverence, playful humour and, above all, vivid yet realistic imagination?

Probing and understanding these processes become more than an exercise in biographical reconstruction if we want to recreate conditions in which scientific creativity, technological innovation and informed imagination can thrive. As Sri Lanka’s long and brutal civil war draws to an end, nurturing creative talent among the country’s youth would be one of the best investments for a peaceful, prosperous future.

But can imagination and innovation take root unless we break free from the shackles of orthodoxy? For transformative change to happen, we will need to rethink certain aspects of our education, bureaucracy, social hierarchies and culture. Are we willing and able to attempt these?

For a start, no modern day Arthur Clarke is going to be inspired by Sri Lanka’s over-crowded and rigid curriculum or the antiquated educational system that places emphasis on rote learning and passing examinations. Throwing computers into the mix has not really modernised the mindset of those in charge. I was recently stunned to learn how the Education Ministry’s much-taunted SchoolNet web connectivity allows students to access only a handful of pre-approved websites! The babus who decided on this must fit the description in this rhyme Sir Arthur was fond of quoting, referring to a British educator of yesteryear: “I’m the master of this college; what I don’t know isn’t knowledge.”

Sir Arthur knew how closed economies and restrictive cultures stifled innovation — he once said the only memorable invention to emerge from Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe was the Rubik’s cube…

He also knew the limits and hazards of ivory tower universities and research institutes. Although he saw value in governments and industry funding research, he didn’t want bean-counters placed in charge of discovery or invention. As he said, “If there had been government research establishments in the Stone Age, we would have had absolutely superb flint tools. But no one would have invented steel.”

A liberal education system and independent academia would be more likely to produce open-minded citizens who actively discuss and debate issues in the public interest. Sir Arthur was a committed public intellectual who always supported evidence-based decision making and the free flow (and interplay) of ideas. Such rigours are essential for imagination and innovation to be rooted in the real world; if not, all we get is hollow fantasy.

Rigorous debate needs to be tempered by open-mindedness. That’s why Sir Arthur regularly stuck his neck out for far-fetched and even ‘crazy’ ideas. He was fond of quoting Mark Twain: “The man with a new idea is a crank –- until the idea succeeds”. Right to the end, he provided moral support to assorted Lankan inventors. He never probed their educational qualifications and instead weighed each idea on its own merit.

He watched with mounting dismay how the state technical institute named after him (the Arthur C Clarke Institute, where he played no role) slowly turned into a mediocre bureaucracy aloof of all ‘cranks’ and most members of the public. Those brushed off by the Institute often found a sympathetic ear and wise counsel in Sir Arthur who was more interested in the song than the singer. That’s another core value that can propel Sri Lanka to a better future.

Second time lucky?

If innovation and imagination are so intangible, how can governments and societies encourage their pursuit? Sir Arthur didn’t have a full answer for this, but he endorsed the approach favoured by his friend and presidential science advisor Professor Cyril Ponnamperuma: “Find the best young minds, give them all facilities, set them goals — and then leave them alone!”

Back in the mid 1980s, there was a glimmer of hope that Sri Lanka was adopting such an approach with the newly established Institute of Fundamental Studies (IFS) and the Arthur Clarke Institute for Modern Technologies (ACCIMT). But alas, that was a flash in the pan: when new ways of creating knowledge and ideas threatened the old guard of scientists and bureaucrats, they mounted a joint assault to reclaim their lost ‘territory’.

A dejected Ponnamperuma returned to the United States, where he died in 1994. A generation of bright-eyed Lankans lost their chance to pursue world class research and innovation in their own land; most migrated to western countries. Sir Arthur, meanwhile, realised the limits of the possible and gradually withdrew from public positions citing reasons of age and health.

If we want to nurture imagination and innovation, we must first learn from the mistakes of the recent past. Obsolete institutions and ossified policies will need to be reformed. Worthy senior academics now past their prime should gracefully retire, or at a minimum, stay out of the way.

Pursuit of this ideal need not be the exclusive domain (or burden) of the state. In fact, private efforts can nurture innovation faster and better. Two current initiatives augur well for the future: LIRNEasia and Institute for Research and Development (IRD). Interestingly, both are headed by returning diaspora scientists who completely ignore the local hierarchies.

Let’s not kid ourselves: sparking imagination and innovation is much harder than launching a gleaming new satellite in Sir Arthur’s name. But the rewards would also be greater: if we get it right this time, Sri Lanka can finally take its rightful place in the 21st century.

What better tribute can we imagine for Sir Arthur Clarke?

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene worked with Sir Arthur C Clarke for 21 years as a research assistant at the latter’s personal office (nothing to do with the Arthur Clarke Institute). He blogs on media, society and development at http://movingimages.wordpress.com