The Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s Total Landscaping exhibition features the work of 29 contemporary artists moving beyond traditional depictions of landscapes and instead exploring how perceptions of land in Sri Lanka have been shaped, contested and transformed. Total Landscaping arrives at a crucial moment when land ownership, belonging and historical narratives surrounding landscapes are being actively debated. Through a dynamic sequence of changing displays, the exhibition invites visitors to reconsider their relationship with land in a deeply immersive and thought provoking way.

Rotation 3 of Total Landscaping features work by Bandu Manamperi, Danushka Marasinghe, Deshan Tennekoon, Isuri Dayaratne, Laki Senanayake, M. Vijitharan, Muhanned Cader, Ruvin de Silva, Sakina Aliakbar, Suntharam Anojan, and Tashiya de Mel.

Groundviews spoke to Sandev Handy and Thinal Sajeewa from the curatorial team to find out how the exhibition was put together.

What inspired the theme for this and how did you come up with the title?

The Total Landscaping exhibition actually came from quite a funny experience, so a funny title. When the previous presidential election was happening in the US, you had Donald Trump losing to Joe Biden. At one of the press conferences there was this bizarre scene with a photo of Rudy Giuliani’s make up. He was part of the Trump campaign. His makeup was running down his face. It looked really awful. They were outside, standing in front of an old garage. On the right was an adult store. Everyone was confused as to the choice of the last press conference of the presidential campaign. What actually happened is Trump’s staff had called the Four Seasons Hotel asking them to book a location. Then they called the number which they found online and confirmed the conference booking. It turns out they hadn’t called the Four Seasons Hotel but Four Seasons Total Landscaping, a landscaping company. That’s so funny. I was fascinated with that term total landscaping. I thought that was an interesting terminology to describe or tell the story of what’s happened in this country – totalised interventions into land and this totalised relationship to land, which have animated every important part of Sri Lankan history in some sense. So that’s where the title came from. The exhibition itself came from a few things. It came from us looking at some early colonial research and colonial archives, looking at the history of botany, the history of how the modern relationship to land has been framed and the widespread land based on issues such as increased land grabbing, land occupation and larger industrial interventions into the landscape – primarily looking at how land is coded and then how land codes us and our relationship to each other.

How did you choose the 29 artists featured in the exhibition?

It was less about the artists and more about the artwork and how it relates to the themes of the show. Initially there is a long period of research, firstly to figure out the themes of the exhibition and what we want to be exploring in terms of speaking about land. Then we look for artworks that have responded to these issues or themes that we’re bringing up. We talk to a lot of these artists, with studio visits, phone calls and meetings in person and online. Some of the artists don’t live in the country, they live overseas. For example, Tashiya De Mel was in the Netherlands for her masters. She went back and forth between Sri Lanka and the Netherlands for a while. It’s about speaking to the artists and figuring out how they’ve perceived their artwork as well. Then we think about whether that will fit into the theme we’ve set out to explore.

What are the different mediums you have on display?

Altogether, in all three rotations, we have about 100 plus artworks. On top of that there are 200 drawings that we showed in the first rotation. We have moving image, sculpture, prints and multiples. Isuri and Deshan’s comic book was initially printed in a comic anthology called Ink Brick. For the exhibition we approached them about the potential of bringing the comic into the museum as an artwork. It’s funny because people are feeling really excited about there being comics in the museum. It’s an artwork. It’s visual culture. It’s being produced by artists. Why would it not be in a museum?

This is the third rotation. How much has the exhibition changed since the first rotation?

Quite a bit. Essentially everything you’re seeing here is being shown for the first time in this exhibition, except for the paddy fields. This is a 10 gallery exhibition. So it’s a much bigger exhibition. While we’re in our temporary space as a museum, moving towards a permanent one, one of the things that we have to balance is questions of access versus the kind of scale that we want. So we could put the whole exhibition in a much larger building but then there’s a limitation of access. Whereas being in a mall, anyone can loiter here for free. Ironically, malls are one of the few places in Sri Lanka where you can actually hang out without spending any money so because of that we have limited space. What we’ve had to do is split the exhibition into three parts.

How do the works relate to the history and culture of land?

It really depends on how we think about land and its history. We don’t necessarily look at the history of land in certain works but just history in general. For example, with Laki Senanayake’s currency notes, we’re looking at the history of how the currency note has changed over time. They reflect what Sri Lanka chose to frame as a national priority, as a national pride. Later on, Laki was commissioned to start looking at the ecology, the flora and fauna of Sri Lanka and how we should be taking care of it and bringing attention to it. Two of the currency notes that we have featured focus on the Mahaweli reservoir and this massive irrigation project that took place. The one directly below that is the parliament building, so we’re also looking at the history of government change. One more thing I should mention is the Victoria Dam as it’s opened in the Mahaweli irrigation project, which Tashiya looks at in her work. She’s looking at it in the contemporary, giving us a tourist image of this area. She’s also talking about the human cost of displacement in the contemporary world. There’s an underlying theme here that Tashiya is wanting us to look at, which is a sort of dependence, fascination and obsession perhaps with hydropower – a kind of hydro-nationalism.

What can visitors expect as they enter the exhibition space?

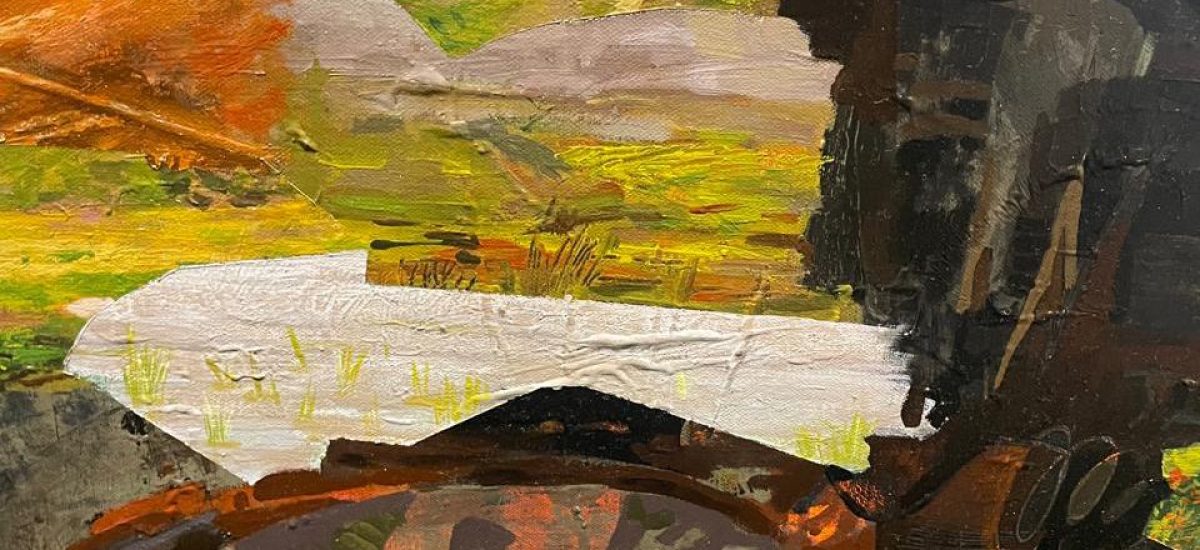

The exhibition opens with Dhanushka Marasinghe’s Paddy Fields. It’s made to reflect how things that resonate with us visually aren’t always innocent. Dhanushka was making this artwork in 2016, post-war pre-constitutional crisis, Easter bombings, COVID economic crisis. It’s this weird golden era where narratives of prosperity and peacefulness are being touted. The checkpoints are disappearing. The cafes are opening up. There is a real optimism. Dhanushka is visiting his family, his hometown. He’s overlooking the acres of paddy fields. It’s the golden hour. There’s really beautiful light and sound. It reminds you that Sri Lanka is such a beautiful, peaceful place. It’s finally here. He hears a sound underneath the paddy fields. It freaks him out because he doesn’t know what it is. It’s like something’s running through the underbrush. He’s enjoying the peacefulness and the serenity of the view and then that sound so quickly changes his relationship to it. He uses that as a metaphor to think about what it is that we’re looking at visually and what’s going on underneath.

Visit Total Landscaping on the ground floor of Crescat Boulevard, Colombo 3 until May 29.